Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, mRNA 1273

CAS 2457298-05-2

An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 expressing the prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spike trimer

- MRNA-1273 SARS-COV-2

- CX 024414

- CX-024414

- CX024414

- mRNA-1273

| NAME | DOSAGE | STRENGTH | ROUTE | LABELLER | MARKETING START | MARKETING END | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covid-19 Vaccine Moderna | Injection | Intramuscular | Moderna Therapeutics Inc | 2020-12-23 | Not applicable | |||

| Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine | Injection, suspension | 0.2 mg/1mL | Intramuscular | Moderna US, Inc. | 2020-12-18 | Not applicable |

| FORM | ROUTE | STRENGTH |

|---|---|---|

| Injection | Intramuscular | |

| Injection, suspension | Intramuscular | 0.2 mg/1mL |

REFNature (London, United Kingdom) (2020), 586(7830), 516-527.bioRxiv (2020), 1-39Nature (London, United Kingdom) (2020), 586(7830), 567-571. Nature Biotechnology (2020), Ahead of PrintJournal of Pure and Applied Microbiology (2020), 14(Suppl.1), 831-840.Chemical & Engineering News (2020), 98(46), 12.New England Journal of Medicine (2020), 383(16), 1544-1555. Science of the Total Environment (2020), 725, 138277.JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association (2020), 324(12), 1125-1127.Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews (2021), 169, 137-151. bioRxiv (2021), 1-62. bioRxiv (2021), 1-51.

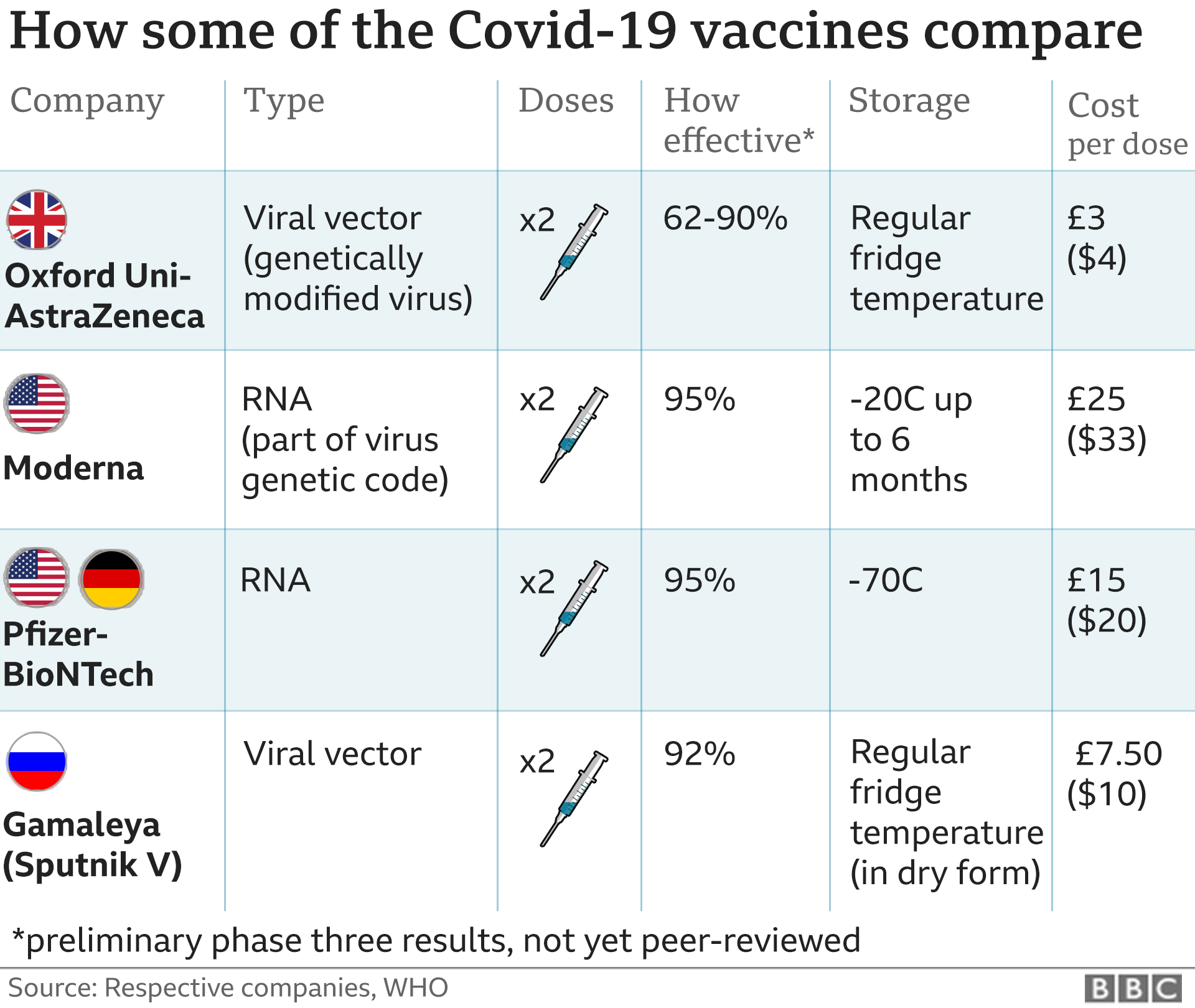

The Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine (mRNA-1273) is a novel mRNA-based vaccine encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle that encodes for a full-length pre-fusion stabilized spike (S) protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, leading to a respiratory illness alongside other complications. COVID-19 has high interpatient variability in symptoms, ranging from mild symptoms to severe illness.5 A phase I, open-label, dose-ranging clinical trial (NCT04283461) was initiated in March 2020 in which 45 subjects received two intramuscular doses (on days 1 and 29).4 This trial was later followed by phase II and III trials, where the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine demonstrated vaccine efficacy of 94.1%.5

On December 18, 2020, the FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine as the second vaccine for the prevention of COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 in patients aged 18 years and older, after the EUA issued for the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 Vaccine on December 11, 2020. The Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine is administered as a series of two intramuscular injections, one month (28 days) apart. In clinical trials, there were no differences in the safety profiles between younger and older (65 years of age and older) study participants; however, the safety and effectiveness of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine have not been assessed in persons less than 18 years of age.5 On December 23, 2020, Health Canada issued an expedited authorization for the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine.7

It is an RNA vaccine composed of nucleoside-modified mRNA (modRNA) encoding a spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which is encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles. It is one of the two RNA vaccines developed and deployed in 2020 against COVID‑19, the other being the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine.The Moderna COVID‑19 vaccine, codenamed mRNA-1273, is a COVID‑19 vaccine developed by the United States National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and Moderna. It is administered by two 0.5 mL doses given by intramuscular injection given four weeks apart.[12]

On 18 December 2020, mRNA-1273 was issued an Emergency Use Authorization by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[6][13][14][15] It was authorized for use in Canada on 23 December 2020,[2][3] in the European Union on 6 January 2021,[10][16][11] and in the United Kingdom on 8 January 2021.[17]

Design

Upon the announcement Moderna’s shares rose dramatically, and the chief executive officer (CEO) and other corporate executives began large program sales of their shareholdings.[26]In January 2020, Moderna announced development of an RNA vaccine, named mRNA-1273, to induce immunity to SARS-CoV-2.[18][19][20] Moderna’s technology uses a nucleoside-modified messenger RNA (modRNA) compound named mRNA-1273. Once the compound is inside a human cell, the mRNA links up with the cell’s endoplasmic reticulum. The mRNA-1273 is encoded to trigger the cell into making a specific protein using the cell’s normal manufacturing process. The vaccine encodes a version of the spike protein called 2P, which includes two stabilizing mutations in which the regular amino acids are replaced with prolines, developed by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases‘ Vaccine Research Center.[21][22][23][24] Once the protein is expelled from the cell, it is eventually detected by the immune system, which begins generating efficacious antibodies. The mRNA-1273 drug delivery system uses a PEGylated lipid nanoparticle drug delivery (LNP) system.[25]

Composition

The vaccine contains the following ingredients:[7][27]

- nucleoside-modified messenger RNA encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein (S) stabilized in its prefusion configuration;[28]

- lipids:

- SM-102,

- polyethylene glycol [PEG] 2000-dimyristoyl glycerol [DMG],

- cholesterol,

- and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine [DSPC];

- tromethamine;

- tromethamine hydrochloride;

- acetic acid;

- sodium acetate;

- and sucrose.

Clinical trials

Phase I / II

In March 2020, the Phase I human trial of mRNA-1273 began in partnership with the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.[29] In April, the U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) allocated up to $483 million for Moderna’s vaccine development.[30] Plans for a Phase II dosing and efficacy trial to begin in May were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[31] Moderna signed a partnership with Swiss vaccine manufacturer Lonza Group,[32] to supply 300 million doses per annum.[33]

On 25 May 2020, Moderna began a Phase IIa clinical trial recruiting six hundred adult participants to assess safety and differences in antibody response to two doses of its candidate vaccine, mRNA-1273, a study expected to complete in 2021.[34] In June 2020, Moderna entered a partnership with Catalent in which Catalent will fill and package the vaccine candidate. Catalent will also provide storage and distribution.[35]

On 9 July, Moderna announced an in-fill manufacturing deal with Laboratorios Farmacéuticos Rovi, in the event that its vaccine is approved.[36]

On 14 July 2020, Moderna scientists published preliminary results of the Phase I dose escalation clinical trial of mRNA-1273, showing dose-dependent induction of neutralizing antibodies against S1/S2 as early as 15 days post-injection. Mild to moderate adverse reactions, such as fever, fatigue, headache, muscle ache, and pain at the injection site were observed in all dose groups, but were common with increased dosage.[37][38] The vaccine in low doses was deemed safe and effective in order to advance a Phase III clinical trial using two 100-μg doses administered 29 days apart.[37]

In July 2020, Moderna announced in a preliminary report that its Operation Warp Speed candidate had led to production of neutralizing antibodies in healthy adults in Phase I clinical testing.[37][39] “At the 100-microgram dose, the one Moderna is advancing into larger trials, all 15 patients experienced side effects, including fatigue, chills, headache, muscle pain, and pain at the site of injection.”[40] The troublesome higher doses were discarded in July from future studies.[40]

Phase III

Moderna and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases began a Phase III trial in the United States on 27 July, with a plan to enroll and assign thirty thousand volunteers to two groups – one group receiving two 100-μg doses of mRNA-1273 vaccine and the other receiving a placebo of 0.9% sodium chloride.[41] As of 7 August, more than 4,500 volunteers had enrolled.

In September 2020, Moderna published the detailed study plan for the clinical trial.[42] On 30 September, CEO Stéphane Bancel said that, if the trial is successful, the vaccine might be available to the public as early as late March or early April 2021.[43] As of October 2020, Moderna had completed the enrollment of 30,000 participants needed for its Phase III trial.[44] The U.S. National Institutes of Health announced on 15 November 2020 that overall trial results were positive.[45]

On 30 December 2020, Moderna published results from the Phase III clinical trial, indicating 94% efficacy in preventing COVID‑19 infection.[46][47][48] Side effects included flu-like symptoms, such as pain at the injection site, fatigue, muscle pain, and headache.[47] The clinical trial is ongoing and is set to conclude in late-2022[49]

In November 2020, Nature reported that “While it’s possible that differences in LNP formulations or mRNA secondary structures could account for the thermostability differences [between Moderna and BioNtech], many experts suspect both vaccine products will ultimately prove to have similar storage requirements and shelf lives under various temperature conditions.”[50]

Since September 2020, Moderna has used Roche Diagnostics‘ Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S test, authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) on 25 November 2020. According to an independent supplier of clinical assays in microbiology, “this will facilitate the quantitative measurement of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and help to establish a correlation between vaccine-induced protection and levels of anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) antibodies.” The partnership was announced by Roche on 9 December 2020.[51]

A review by the FDA in December 2020, of interim results of the Phase III clinical trial on mRNA-1273 showed it to be safe and effective against COVID‑19 infection resulting in the issuance of an EUA by the FDA.[13]

It remains unknown whether the Moderna vaccine candidate is safe and effective in people under age 18 and how long it provides immunity.[47] Pregnant and breastfeeding women were also excluded from the initial trials used to obtain Emergency Use Authorization,[52] though trials in those populations are expected to be performed in 2021.[53]

In January 2021, Moderna announced that it would be offering a third dose of its vaccine to people who were vaccinated twice in its Phase I trial. The booster would be made available to participants six to twelve months after they got their second doses. The company said it may also study a third shot in participants from its Phase III trial, if antibody persistence data warranted it.[54][55][56]

In January 2021, Moderna started development of a new form of its vaccine, called mRNA-1273.351, that could be used as a booster shot against the 501.V2 variant of SARS-CoV-2 first detected in South Africa.[57][58] It also started testing to see if a third shot of the existing vaccine could be used to fend off the virus variants.[58] On 24 February, Moderna announced that it had manufactured and shipped sufficient amounts of mRNA-1273.351 to the National Institutes of Health to run Phase{ I clinical trials.[59] To increase the span of vaccination beyond adults, Moderna started the clinical trials of vaccines on childern age six to eleven in the U.S. and in Canada.[60]

Storage requirements

Moderna vaccine being stored in a conventional medical freezer

The Moderna news followed preliminary results from the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine candidate, BNT162b2, with Moderna demonstrating similar efficacy, but requiring storage at the temperature of a standard medical refrigerator of 2–8 °C (36–46 °F) for up to 30 days or −20 °C (−4 °F) for up to four months, whereas the Pfizer-BioNTech candidate requires ultracold freezer storage between −80 and −60 °C (−112 and −76 °F).[61][47] Low-income countries usually have cold chain capacity for refrigerator storage.[62][63] In February 2021, the restrictions on the Pfizer vaccine were relaxed when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) updated the emergency use authorization (EUA) to permit undiluted frozen vials of the vaccine to be transported and stored at between −25 and −15 °C (−13 and 5 °F) for up to two weeks before use.[27][64][65]

Efficacy

The interim primary efficacy analysis was based on the per-protocol set, which consisted of all participants with negative baseline SARS-CoV-2 status and who received two doses of investigational product per schedule with no major protocol deviations. The primary efficacy endpoint was vaccine efficacy (VE) in preventing protocol defined COVID-19 occurring at least 14 days after dose 2. Cases were adjudicated by a blinded committee. The primary efficacy success criterion would be met if the null hypothesis of VE ≤30% was rejected at either the interim or primary analysis. The efficacy analysis presented is based on the data at the first pre-specified interim analysis timepoint consisting of 95 adjudicated cases.[66] The data are presented below.

| Primary endpoint: COVID-19 | Cases n (%) Incidence per 1000 person-years | Vaccine efficacy (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine group (N = 13,934) | Placebo group (N = 13,883) | ||

| All participants | 5 cases in 13,934 (<0.1%)1.840 | 90 cases in 13,883 (0.6%)33.365 | 94.5% (86.5-97.8%) |

| Participants 18–64 years of age | 5 cases in 10,407 (<0.1%)2.504 | 75 cases in 10,384 (0.7%)37.788 | 93.4% (83.7-97.3%) |

| 65 and older | 0 cases in 3,527 | 15 cases in 3,499 (0.4%) | 100% |

| Chronic lung disease | 0/661 | 6/673 | 100% |

| Significant cardiac disease | 0/686 | 3/678 | 100% |

| Severe obesity (BMI>40) | 1/901 | 11/884 | 91.2% (32-98.9%) |

| Diabetes | 0/1338 | 7/1309 | 100% |

| Liver disease | 0/93 | 0/90 | |

| Obesity (BMI>30) | 2/5269 | 46/5207 | 95.8% (82.6-99%) |

Manufacturing

An insulated shipping container with Moderna vaccine boxes ensconced by cold packs

Moderna is relying extensively on contract manufacturing organizations to scale up its vaccine manufacturing process. Moderna has contracted with Lonza Group to manufacture the vaccine at facilities in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in the United States, and in Visp in Switzerland, and is purchasing the necessary lipid excipients from CordenPharma.[67] For the tasks of filling and packaging vials, Moderna has entered into contracts with Catalent in the United States and Laboratorios Farmacéuticos Rovi in Spain.[67]

Purchase commitments

In June 2020, Singapore signed a pre-purchase agreement for Moderna, reportedly paying a price premium in order to secure early stock of vaccines, although the government declined to provide the actual price and quantity, citing commercial sensitivities and confidentiality clauses.[68][69]

On 11 August 2020, the U.S. government signed an agreement to buy one hundred million doses of Moderna’s anticipated vaccine,[70] which the Financial Times said Moderna planned to price at US$50–60 per course.[71] On November 2020, Moderna said it will charge governments who purchase its vaccine between US$25 and US$37 per dose while the E.U. is seeking a price of under US$25 per dose for the 160 million doses it plans to purchase from Moderna.[72][73]

In 2020, Moderna also obtained purchase agreements for mRNA-1273 with the European Union for 160 million doses and with Canada for up to 56 million doses.[74][75] On 17 December, a tweet by the Belgium Budget State Secretary revealed the E.U. would pay US$18 per dose, while The New York Times reported that the U.S. would pay US$15 per dose.[76]

In February 2021, Moderna said it was expecting US$18.4 billion in sales of its COVID-19 vaccine.[77]

Authorizations

| show Full authorizationshow Emergency authorization Eligible COVAX recipient (assessment in progress)[96] |

Expedited

U.S. military personnel being administered the Moderna vaccineKamala Harris, Vice President of the United States, receiving her second dose of the Moderna vaccination in January 2021.

As of December 2020, mRNA-1273 was under evaluation for emergency use authorization (EUA) by multiple countries which would enable rapid rollout of the vaccine in the United Kingdom, the European Union, Canada, and the United States.[97][98][99][100]

On 18 December 2020, mRNA-1273 was authorized by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under an EUA.[6][8][13] This is the first product from Moderna that has been authorized by the FDA.[101][14]

On 23 December 2020, mRNA-1273 was authorized by Health Canada.[2][3] Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had previously said deliveries would begin within 48 hours of approval and that 168,000 doses would be delivered by the end of December.[102]

On 5 January 2021, mRNA-1273 was authorized for use in Israel by its Ministry of Health.[103]

On 3 February 2021, mRNA-1273 was authorized for use in Singapore by its Health Sciences Authority;[104] the first shipment arrived on 17 February.[105]

Standard

On 6 January 2021, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended granting conditional marketing authorization[10][106] and the recommendation was accepted by the European Commission the same day.[11][16]

On 12 January 2021, Swissmedic granted temporary authorization for the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine in Switzerland.[107][108]

Society and culture

Controversies

In May 2020, after releasing partial and non-peer reviewed results for only eight of 45 candidates in a preliminary pre-Phase I stage human trial directly to financial markets, the CEO announced on CNBC an immediate $1.25 billion rights issue to raise funds for the company, at a $30 billion valuation,[109] while Stat said, “Vaccine experts say Moderna didn’t produce data critical to assessing COVID-19 vaccine.”[110]

On 7 July, disputes between Moderna and government scientists over the company’s unwillingness to share data from the clinical trials were revealed.[111]

Moderna also faced criticism for failing to recruit people of color in clinical trials.[112]

Patent litigation

The PEGylated lipid nanoparticle (LNP) drug delivery system of mRNA-1273 has been the subject of ongoing patent litigation with Arbutus Biopharma, from whom Moderna had previously licensed LNP technology.[25][113] On 4 September 2020, Nature Biotechnology reported that Moderna had lost a key challenge in the ongoing case.[114]

Notes

- ^ US authorization also includes the three sovereign nations in the Compact of Free Association: Palau, the Marshall Islands, and Micronesia.[93][94]

References

- ^ Moderna (23 October 2019). mRNA-3704 and Methylmalonic Acidemia (Video). YouTube. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Regulatory Decision Summary – Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine”. Health Canada. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine (mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2)”. COVID-19 vaccines and treatments portal. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ “Information for Healthcare Professionals on COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna”. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 8 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ “Conditions of Authorisation for COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna”. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 8 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “FDA Takes Additional Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for Second COVID-19 Vaccine”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine – cx-024414 injection, suspension”. DailyMed. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine Emergency Use Authorization(PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Report). 18 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ “Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine Standing Orders for Administering Vaccine to Persons 18 Years of Age and Older” (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna EPAR”. European Medicines Agency (EMA). Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “European Commission authorises second safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19”. European Commission(Press release). Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ “Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine”. Dosing & Administration. Infectious Diseases Society of America. 4 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Statement from NIH and BARDA on the FDA Emergency Use Authorization of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine”. US National Institutes of Health. 18 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, Wallace M, Curran KG, Chamberland M, et al. (January 2021). “The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ Interim Recommendation for Use of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine – United States, December 2020”(PDF). MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (5152): 1653–56. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm695152e1. PMID 33382675. S2CID 229945697.

- ^ Lovelace Jr B (19 December 2020). “FDA approves second Covid vaccine for emergency use as it clears Moderna’s for U.S. distribution”. CNBC. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna”. Union Register of medicinal products. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ “Moderna vaccine becomes third COVID-19 vaccine approved by UK regulator”. U.K. Government. 8 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Steenhuysen J, Kelland K (24 January 2020). “With Wuhan virus genetic code in hand, scientists begin work on a vaccine”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Carey K (26 February 2020). “Increasing number of biopharma drugs target COVID-19 as virus spreads”. BioWorld. Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Everett G (27 February 2020). “These 5 drug developers have jumped this week on hopes they can provide a coronavirus treatment”. Markets Insider. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ “The tiny tweak behind COVID-19 vaccines”. Chemical & Engineering News. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September2020.

- ^ “A gamble pays off in ‘spectacular success’: How the leading coronavirus vaccines made it to the finish line”. Washington Post. 6 December 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Kramer, Jillian (31 December 2020). “They spent 12 years solving a puzzle. It yielded the first COVID-19 vaccines”. National Geographic.

- ^ Corbett, Kizmekia; Edwards, Darin; Leist, Sarah (5 August 2020). “SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Development Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness”. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2622-0. PMC 7301911. PMID 32577634.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Auth DR, Powell MB (14 September 2020). “Patent Issues Highlight Risks of Moderna’s COVID-19 Vaccine”. New York Law Journal. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Pendleton D, Maloney T (18 May 2020). “MIT Professor’s Moderna Stake on the Brink of Topping $1 Billion”. Bloomberg News. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

CEO Bancel, other Moderna executives have been selling shares

- ^ Jump up to:a b Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers Administering Vaccine(PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Report). December 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 – Preliminary Report, Lisa A. Jackson et al., New England Journal of Medicine 383 (Nov. 12, 2020), pp. 1920-1931, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483.

- ^ “NIH clinical trial of investigational vaccine for COVID-19 begins”. National Institutes of Health (NIH). 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March2020.

- ^ Kuznia R, Polglase K, Mezzofiore G (1 May 2020). “In quest for vaccine, US makes ‘big bet’ on company with unproven technology”. CNN. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Keown A (7 May 2020). “Moderna moves into Phase II testing of COVID-19 vaccine candidate”. BioSpace. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ Blankenship K (1 May 2020). “Moderna aims for a billion COVID-19 shots a year with Lonza manufacturing tie-up”. FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ “Swiss factory rushes to prepare for Moderna Covid-19 vaccine”. SWI swissinfo.ch. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT04405076 for “Dose-Confirmation Study to Evaluate the Safety, Reactogenicity, and Immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccine in Adults Aged 18 Years and Older” at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ “Moderna eyes third quarter for first doses of potential COVID-19 vaccine with Catalent deal”. Reuters. 25 June 2020. Archivedfrom the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November2020.

- ^ Lee J. “Moderna signs on for another COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing deal”. MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Coler RN, et al. (November 2020). “An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 – Preliminary Report”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (20): 1920–1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. PMC 7377258. PMID 32663912.

- ^ Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Coler RN, et al. (November 2020). “An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 – Preliminary Report”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (20): 1920–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. PMC 7377258. PMID 32663912.

- ^ Li Y (14 July 2020). “Dow futures jump more than 200 points after Moderna says its vaccine produces antibodies to coronavirus”. CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Herper M, Garde D (14 July 2020). “First data for Moderna Covid-19 vaccine show it spurs an immune response”. Stat. Boston Globe Media. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Palca J (27 July 2020). “COVID-19 vaccine candidate heads to widespread testing in U.S.” NPR. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ “Moderna, in bid for transparency, discloses detailed plan of coronavirus vaccine trial”. BioPharma Dive. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Mascarenhas L (1 October 2020). “Moderna chief says Covid-19 vaccine could be widely available by late March”. CNN. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Cohen E. “First large-scale US Covid-19 vaccine trial reaches target of 30,000 participants”. CNN. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ “Promising Interim Results from Clinical Trial of NIH-Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine”. National Institutes of Health (NIH). 15 November 2020.

- ^ Baden, Lindsey R. (30 December 2020). “Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine”. New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (5): 403–416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. PMC 7787219. PMID 33378609.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Lovelace Jr B, Higgins-Dunn N (16 November 2020). “Moderna says preliminary trial data shows its coronavirus vaccine is more than 94% effective, shares soar”. CNBC. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Zimmer C (20 November 2020). “2 Companies Say Their Vaccines Are 95% Effective. What Does That Mean? You might assume that 95 out of every 100 people vaccinated will be protected from Covid-19. But that’s not how the math works”. The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT04470427 for “A Study to Evaluate Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Adults Aged 18 Years and Older to Prevent COVID-19” at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Dolgin E (November 2020). “COVID-19 vaccines poised for launch, but impact on pandemic unclear”. Nature Biotechnology. doi:10.1038/d41587-020-00022-y. PMID 33239758. S2CID 227176634.

- ^ “Moderna Use Roche Antibody Test During Vaccine Trials”. rapidmicrobiology.com. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Pregnant women haven’t been included in promising COVID-19 vaccine trials

- ^ FDA: Leave the door open to Covid-19 vaccination for pregnant and lactating health workers

- ^ Rio, Giulia McDonnell Nieto del (15 January 2021). “Covid-19: Over Two Million Around the World Have Died From the Virus”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 January2021.

- ^ Tirrell, Meg (14 January 2021). “Moderna looks to test Covid-19 booster shots a year after initial vaccination”. CNBC. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ “Moderna Explores Whether Third Covid-19 Vaccine Dose Adds Extra Protection”. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 18 January2021.

- ^ “Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine Update” (PDF). 25 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Is the Covid-19 Vaccine Effective Against New South African Variant?”. The New York Times. 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ “Moderna Announces it has Shipped Variant-Specific Vaccine Candidate, mRNA-1273.351, to NIH for Clinical Study”. Moderna Inc. (Press release). 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February2021.

- ^ Loftus, Peter (16 March 2021). “Moderna Is Testing Its Covid-19 Vaccine on Young Children”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ “Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Vaccination Storage & Dry Ice Safety Handling”. Pfizer. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ “How China’s COVID-19 could fill the gaps left by Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca”. Fortune. 5 December 2020. Archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December2020.

- ^ “Pfizer’s Vaccine Is Out of the Question as Indonesia Lacks Refrigerators: State Pharma Boss”. Jakarta Globe. 22 November 2020. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Allows More Flexible Storage, Transportation Conditions for Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Press release). 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ “Pfizer and BioNTech Submit COVID-19 Vaccine Stability Data at Standard Freezer Temperature to the U.S. FDA”. Pfizer (Press release). 19 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mullin R (25 November 2020). “Pfizer, Moderna ready vaccine manufacturing networks”. Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ “Securing Singapore’s access to COVID-19 vaccines”. http://www.gov.sg. Singapore Government. 14 December 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Khalik, Salma (1 February 2021). “How Singapore picked its Covid-19 vaccines”. The Straits Times. Retrieved 1 February2021.

- ^ “Trump says U.S. inks agreement with Moderna for 100 mln doses of COVID-19 vaccine candidate”. Yahoo. Reuters. 11 August 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ “Moderna aims to price coronavirus vaccine at $50-$60 per course: FT”. Reuters. 28 July 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ “Donald Trump appears to admit Covid is ‘running wild’ in the US”. The Guardian. 22 November 2020. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

Moderna told the Germany [sic] weekly Welt am Sonntag that it will charge governments between $25 and $37 per dose of its Covid vaccine candidate, depending on the amount ordered.

- ^ Guarascio F (24 November 2020). “EU secures 160 million doses of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine”. Reuters. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ “Coronavirus: Commission approves contract with Moderna to ensure access to a potential vaccine”. European Commission. 25 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ “New agreements to secure additional vaccine candidates for COVID-19”. Prime Minister’s Office, Government of Canada. 25 September 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Stevis-Gridneff M, Sanger-Katz M, Weiland N (18 December 2020). “A European Official Reveals a Secret: The U.S. Is Paying More for Coronavirus Vaccines”. The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ “Moderna sees $18.4 billion in sales from COVID-19 vaccine in 2021”. Reuters. 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ “EMA recommends COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna for authorisation in the EU” (Press release). European Medicines Agency. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ “COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna”. Union Register of medicinal products. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Endnu en vaccine mod COVID-19 er godkendt af EU-Kommissionen”. Lægemiddelstyrelsen (in Danish). Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ “COVID-19: Bóluefninu COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna frá hefur verið veitt skilyrt íslenskt markaðsleyfi”. Lyfjastofnun (in Icelandic). Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ “Status på koronavaksiner under godkjenning per 6. januar 2021”. Statens legemiddelverk (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ “Informació en relació amb la vacunació contra la COVID-19”(PDF). Govern d’Andorra. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ “Regulatory Decision Summary – Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine”. Health Canada, Government of Canada. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ “Drug and vaccine authorizations for COVID-19: List of applications received”. Health Canada, Government of Canada. 9 December 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ “Israeli Ministry of Health Authorizes COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna for Use in Israel”. modernatx.com. 4 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ “Public Health (Emergency Authorisation of COVID-19 Vaccine) Rules, 2021” (PDF). Government of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ “AstraZeneca and Moderna vaccines to be administered in Saudi Arabia”. Gulf News. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ “Singapore becomes first in Asia to approve Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine”. Reuters. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ “Swissmedic grants authorisation for the COVID-19 vaccine from Moderna” (Press release). Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic). 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January2020.

- ^ “Information for Healthcare Professionals on COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna”. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 8 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ “Conditions of Authorisation for COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna”. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 8 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ “Interior Applauds Inclusion of Insular Areas through Operation Warp Speed to Receive COVID-19 Vaccines” (Press release). United States Department of the Interior (DOI). 12 December 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ Dorman B (6 January 2021). “Asia Minute: Palau Administers Vaccines to Keep Country Free of COVID”. Hawaii Public Radio. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ “Vietnam approves US, Russia Covid-19 vaccines for emergency use”. VnExpress. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ “Regulation and Prequalification”. World Health Organization. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Cohen E (30 November 2020). “Moderna applies for FDA authorization for its Covid-19 vaccine”. CNN. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Burger L (1 December 2020). “COVID-19 vaccine sprint as Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna seek emergency EU approval”. Reuters. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Kuchler H (30 November 2020). “Canada could be among the first to clear Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine for use”. The Financial Post. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Parsons L (28 October 2020). “UK’s MHRA starts rolling review of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine”. PharmaTimes. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Lee J. “Moderna nears its first-ever FDA authorization, for its COVID-19 vaccine”. MarketWatch. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Austen, Ian (23 December 2020). “Canada approves the Moderna vaccine, paving the way for inoculations in its vast Far North”. The New York Times. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ “Israel authorises use of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine”. Yahoo! News. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ “Singapore becomes first in Asia to approve Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine”. Reuters. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ “First shipment of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine arrives in Singapore”. CNA. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ “EMA recommends COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna for authorisation in the EU” (Press release). European Medicines Agency. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Miller, John (12 January 2021). “Swiss drugs regulator approves Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine”. Reuters. Retrieved 17 January2021.

- ^ “Swissmedic grants authorisation for the COVID-19 vaccine from Moderna”. Swissmedic (Press release). 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ Hiltzik M (19 May 2020). “Column: Moderna’s vaccine results boosted its share offering – and it’s hardly a coincidence”. The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Branswell H (19 May 2020). “Vaccine experts say Moderna didn’t produce data critical to assessing Covid-19 vaccine”. Stat. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Taylor M, Respaut R (7 July 2020). “Exclusive: Moderna spars with U.S. scientists over COVID-19 vaccine trials”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ “Moderna vaccine trial contractors fail to enroll enough people of color, prompting slowdown”. NBC News. Reuters. 6 October 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Vardi N (29 June 2020). “Moderna’s Mysterious Coronavirus Vaccine Delivery System”. Forbes. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ “Moderna loses key patent challenge”. Nature Biotechnology. 38 (9): 1009. September 2020. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0674-1. PMID 32887970. S2CID 221504018.

Further reading

- World Health Organization (2021). Background document on the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) against COVID-19: background document to the WHO Interim recommendations for use of the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna), 3 February 2021 (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/339218. WHO/2019-nCoV/vaccines/SAGE_recommendation/mRNA-1273/background/2021.1.

External links

| Scholia has a profile for mRNA-1273 (Q87775025). |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:MRNA-1273. |

- “VRBPAC mRNA-1273 Sponsor Briefing Document” (PDF). Moderna. 17 December 2020.

- “Clinical Study Protocol mRNA-1273-P301” (PDF). Moderna.

- COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna assessment report European Medicines Agency

- “How Moderna’s Covid-19 Vaccine Works”. The New York Times.

- “Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

| Vials of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Vaccine type | RNA |

| Clinical data | |

| Pronunciation | /məˈdɜːrnə/ mə-DUR-nə[1] |

| Trade names | Moderna COVID‑19 Vaccine, COVID‑19 Vaccine Moderna |

| Other names | mRNA-1273, CX-024414, COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Moderna |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information |

| MedlinePlus | a621002 |

| License data | US DailyMed: Moderna_COVID-19_Vaccine |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular |

| ATC code | None |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | CA: Schedule D; Authorized by interim order [2][3]UK: Conditional and temporary authorization to supply [4][5]US: Standing Order; Unapproved (Emergency Use Authorization)[6][7][8][9]EU: Conditional marketing authorization granted [10][11] |

| Identifiers | |

| DrugBank | DB15654 |

| UNII | EPK39PL4R4 |

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (virus)COVID-19 (disease) |

| showTimeline |

| showLocations |

| showInternational response |

| showMedical response |

| showImpact |

| COVID-19 Portal |

| vte |

- Kaur SP, Gupta V: COVID-19 Vaccine: A comprehensive status report. Virus Res. 2020 Oct 15;288:198114. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198114. Epub 2020 Aug 13. [PubMed:32800805]

- Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Coler RN, McCullough MP, Chappell JD, Denison MR, Stevens LJ, Pruijssers AJ, McDermott A, Flach B, Doria-Rose NA, Corbett KS, Morabito KM, O’Dell S, Schmidt SD, Swanson PA 2nd, Padilla M, Mascola JR, Neuzil KM, Bennett H, Sun W, Peters E, Makowski M, Albert J, Cross K, Buchanan W, Pikaart-Tautges R, Ledgerwood JE, Graham BS, Beigel JH: An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 – Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jul 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. [PubMed:32663912]

- Pharmaceutical Business Review: Moderna’s mRNA-1273 vaccine [Link]

- Clinical Trials: Safety and Immunogenicity Study of 2019-nCoV Vaccine (mRNA-1273) for Prophylaxis SARS CoV-2 Infection [Link]

- FDA EUA Drug Products: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine [Link]

- FDA Press Announcements: FDA Takes Additional Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for Second COVID-19 Vaccine [Link]

- Health Canada: Regulatory Decision Summary – Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine [Link]

////////CX 024414, CX-024414, CX024414, mRNA 1273, Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, COVID 19, CORONA VIRUS

CX 024414, CX-024414, CX024414, mRNA 1273, Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, COVID 19, CORONA VIRUS

#CX 024414,#CX-024414, #CX024414, #mRNA 1273, #Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, #COVID 19, #CORONA VIRUS

adjuvant. The purified protein is encoded by the genetic sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein and is produced in insect cells. It can neither cause COVID-19 nor can it replicate, is stable at 2°C to 8°C (refrigerated) and is shipped in a ready-to-use liquid formulation that permits distribution using existing vaccine supply chain channels.

adjuvant. The purified protein is encoded by the genetic sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein and is produced in insect cells. It can neither cause COVID-19 nor can it replicate, is stable at 2°C to 8°C (refrigerated) and is shipped in a ready-to-use liquid formulation that permits distribution using existing vaccine supply chain channels. $475.2 Million (2020)

$475.2 Million (2020)

2-Deoxy-3,5-di-O-(phenylacetyl)-beta-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl chloride (I) is condensed with 2,4-bis-O-(trimethylsilyl)-5(E)-(2-bromovinyl)uracil (II) in acetonitrile (Lewis acid catalyst), or in CHCl3-pyridine (Bronsted acid catalyst), to produce 3,5-di-O-(phenylacetyl)-5(E)-(2-bromovinyl)-2-deoxyuridine (III) and its anomer that is eliminated by TLC (silicagel). Finally, (III) is treated with sodium methoxide in methanol.

2-Deoxy-3,5-di-O-(phenylacetyl)-beta-D-erythro-pentofuranosyl chloride (I) is condensed with 2,4-bis-O-(trimethylsilyl)-5(E)-(2-bromovinyl)uracil (II) in acetonitrile (Lewis acid catalyst), or in CHCl3-pyridine (Bronsted acid catalyst), to produce 3,5-di-O-(phenylacetyl)-5(E)-(2-bromovinyl)-2-deoxyuridine (III) and its anomer that is eliminated by TLC (silicagel). Finally, (III) is treated with sodium methoxide in methanol.

et al., 1986). For more on the synthesis of the erythromycins, see Paterson and Mansuri (1985).

et al., 1986). For more on the synthesis of the erythromycins, see Paterson and Mansuri (1985).

![Chemical structure of N-[2-[[2-[2-[(2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino]phenyl]acetyl]oxy]ethyl]hyaluronamide (diclofenac etalhyaluronate, SI-613)](http://www.researchgate.net/publication/325304331/figure/fig1/AS:669091362766859@1536535220444/Chemical-structure-of.png)