![]()

![Image result for GSK2330672]()

![Image result for GSK2330672]()

GSK 2330672

GSK 672; GSK-2330672

RN: 1345982-69-5

UNII: 386012Z45S

CAS: 1345982-69-5

Chemical Formula: C28H38N2O7S

Molecular Weight: 546.68

Pentanedioic acid, 3-((((3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-7-methoxy-1,1-dioxido-5-phenyl-1,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl)methyl)amino)-

Pentanedioic acid, 3-((((3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-7-methoxy-1,1-dioxido-5-phenyl-1,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl)methyl)amino)-

3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl- 2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid

3-[[[(3R,5R)-3-Butyl-3-ethyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-7-methoxy-1,1-dioxido-5-phenyl-1,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl]amino]pentanedioic acid

- Originator GlaxoSmithKline

- Class Antihyperglycaemics

- Mechanism of Action Sodium-bile acid cotransporter-inhibitors

Highest Development Phases

- Phase II Primary biliary cirrhosis; Pruritus; Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Phase I Cholestasis

Most Recent Events

- 01 Jan 2017 Phase-II clinical trials in Pruritus in USA (PO) (NCT02966834)

- 14 Nov 2016 GlaxoSmithKline completes a phase I trial for Cholestasis in Healthy volunteers in Japan (PO, Tablet) (NCT02801981)

- 11 Nov 2016 Efficacy, safety and pharmacodynamic data from a phase II trial in Primary biliary cirrhosis and Pruritus presented at The Liver Meeting® 2016: 67th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD-2016)

![Christopher Aquino]()

Christopher Joseph Aquino

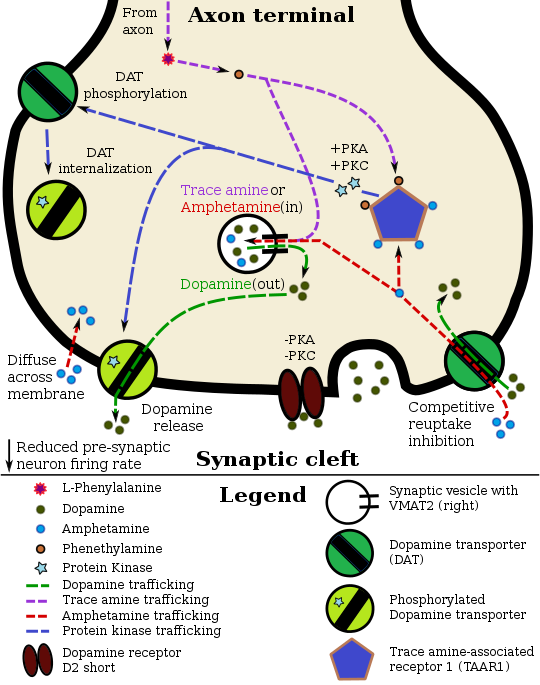

GSK2330672 , an ileal bile acid transport (iBAT) inhibitor indicated for diabetes type II and cholestatic pruritus, is currently under Phase IIb evaluation in the clinic. The API is a highly complex molecule containing two stereogenic centers, one of which is quaternary

GSK-2330672 is highly potent, nonabsorbable apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor for treatment of type 2 diabetes.

More than 200 million people worldwide have diabetes. The World Health Organization estimates that 1 .1 million people died from diabetes in 2005 and projects that worldwide deaths from diabetes will double between 2005 and 2030. New chemical compounds that effectively treat diabetes could save millions of human lives.

Diabetes refers to metabolic disorders resulting in the body’s inability to effectively regulate glucose levels. Approximately 90% of all diabetes cases are a result of type 2 diabetes whereas the remaining 10% are a result of type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes, and latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA). All forms of diabetes result in elevated blood glucose levels and, if left untreated chronically, can increase the risk of macrovascular (heart disease, stroke, other forms of cardiovascular disease) and microvascular [kidney failure (nephropathy), blindness from diabetic retinopathy, nerve damage (diabetic neuropathy)] complications.

Type 1 diabetes, also known as juvenile or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), can occur at any age, but it is most often diagnosed in children, adolescents, or young adults. Type 1 diabetes is caused by the autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells, resulting in an inability to produce sufficient insulin. Insulin controls blood glucose levels by promoting transport of blood glucose into cells for energy use. Insufficient insulin production will lead to decreased glucose uptake into cells and result in accumulation of glucose in the bloodstream. The lack of available glucose in cells will eventually lead to the onset of symptoms of type 1 diabetes: polyuria (frequent urination), polydipsia (thirst), constant hunger, weight loss, vision changes, and fatigue. Within 5-10 years of being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, patient’s insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas are completely destroyed, and the body can no longer produce insulin. As a result, patients with type 1 diabetes will require daily administration of insulin for the remainder of their lives.

Type 2 diabetes, also known as non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) or adult-onset diabetes, occurs when the pancreas produces insufficient insulin and/or tissues become resistant to normal or high levels of insulin (insulin resistance), resulting in excessively high blood glucose levels. Multiple factors can lead to insulin resistance including chronically elevated blood glucose levels, genetics, obesity, lack of physical activity, and increasing age. Unlike type 1 diabetes, symptoms of type 2 diabetes are more salient, and as a result, the disease may not be diagnosed until several years after onset with a peak prevalence in adults near an age of 45 years. Unfortunately, the incidence of type 2 diabetes in children is increasing.

The primary goal of treatment of type 2 diabetes is to achieve and maintain glycemic control to reduce the risk of microvascular (diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, or nephropathy) and macrovascular (heart disease, stroke, other forms of cardiovascular disease) complications. Current guidelines for the treatment of type 2 diabetes from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) [Diabetes Care, 2008, 31 (12), 1 ] outline lifestyle modification including weight loss and increased physical activity as a primary therapeutic approach for management of type 2 diabetes. However, this approach alone fails in the majority of patients within the first year, leading physicians to prescribe medications over time. The ADA and EASD recommend metformin, an agent that reduces hepatic glucose production, as a Tier 1 a medication; however, a significant number of patients taking metformin can experience gastrointestinal side effects and, in rare cases, potentially fatal lactic acidosis. Recommendations for Tier 1 b class of medications include sulfonylureas, which stimulate pancreatic insulin secretion via modulation of potassium channel activity, and exogenous insulin. While both medications rapidly and effectively reduce blood glucose levels, insulin requires 1 -4 injections per day and both agents can cause undesired weight gain and potentially fatal hypoglycemia. Tier 2a recommendations include newer agents such as thiazolidinediones (TZDs pioglitazone and rosiglitazone), which enhance insulin sensitivity of muscle, liver and fat, as well as GLP-1 analogs, which enhance postprandial glucose-mediated insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. While TZDs show robust, durable control of blood glucose levels, adverse effects include weight gain, edema, bone fractures in women, exacerbation of congestive heart failure, and potential increased risk of ischemic cardiovascular events. GLP-1 analogs also effectively control blood glucose levels, however, this class of medications requires injection and many patients complain of nausea. The most recent addition to the Tier 2 medication list is DPP-4 inhibitors, which, like GLP-1 analogs, enhance glucose- medicated insulin secretion from beta cells. Unfortunately, DPP-4 inhibitors only modestly control blood glucose levels, and the long-term safety of DPP-4 inhibitors remains to be firmly established. Other less prescribed medications for type 2 diabetes include a-glucosidase inhibitors, glinides, and amylin analogs. Clearly, new medications with improved efficacy, durability, and side effect profiles are needed for patients with type 2 diabetes.

GLP-1 and GIP are peptides, known as incretins, that are secreted by L and K cells, respectively, from the gastrointestinal tract into the blood stream following ingestion of nutrients. This important physiological response serves as the primary signaling mechanism between nutrient (glucose/fat) concentration in the

gastrointestinal tract and other peripheral organs. Upon secretion, both circulating peptides initiate signals in beta cells of the pancreas to enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, which, in turn, controls glucose concentrations in the blood stream (For reviews see: Diabetic Medicine 2007, 24(3), 223; Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2009, 297(1-2), 127; Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes 2001 , 109(Suppl. 2), S288).

The association between the incretin hormones GLP-1 and GIP and type 2 diabetes has been extensively explored. The majority of studies indicate that type 2 diabetes is associated with an acquired defect in GLP-1 secretion as well as GIP action (see Diabetes 2007, 56(8), 1951 and Current Diabetes Reports 2006, 6(3), 194). The use of exogenous GLP-1 for treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes is severely limited due to its rapid degradation by the protease DPP-4. Multiple modified peptides have been designed as GLP-1 mimetics that are DPP-4 resistant and show longer half-lives than endogenous GLP-1 . Agents with this profile that have been shown to be highly effective for treatment of type 2 diabetes include exenatide and liraglutide, however, these agents require injection. Oral agents that inhibit DPP-4, such as sitagliptin vildagliptin, and saxagliptin, elevate intact GLP-1 and modestly control circulating glucose levels (see Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2010, 125(2), 328; Diabetes Care 2007, 30(6), 1335; Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs 2008, 13(4), 593). New oral medications that increase GLP-1 secretion would be desirable for treatment of type 2 diabetes.

Bile acids have been shown to enhance peptide secretion from the

gastrointestinal tract. Bile acids are released from the gallbladder into the small intestine after each meal to facilitate digestion of nutrients, in particular fat, lipids, and lipid-soluble vitamins. Bile acids also function as hormones that regulate cholesterol homeostasis, energy, and glucose homeostasis via nuclear receptors (FXR, PXR, CAR, VDR) and the G-protein coupled receptor TGR5 (for reviews see: Nature Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 672; Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2008, 10, 1004). TGR5 is a member of the Rhodopsin-like subfamily of GPCRs (Class A) that is expressed in intestine, gall bladder, adipose tissue, liver, and select regions of the central nervous system. TGR5 is activated by multiple bile acids with lithocholic and deoxycholic acids as the most potent activators {Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2008, 51(6), 1831 ). Both deoxycholic and lithocholic acids increase GLP-1 secretion from an enteroendocrine STC-1 cell line, in part through TGR5

{Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2005, 329, 386). A synthetic TGR5 agonist INT-777 has been shown to increase intestinal GLP-1 secretion in vivo in mice {Cell Metabolism 2009, 10, 167). Bile salts have been shown to promote secretion of GLP-1 from colonic L cells in a vascularly perfused rat colon model {Journal of Endocrinology 1995, 145(3), 521 ) as well as GLP-1 , peptide YY (PYY), and neurotensin in a vascularly perfused rat ileum model {Endocrinology 1998, 139(9), 3780). In humans, infusion of deoxycholate into the sigmoid colon produces a rapid and marked dose responsive increase in plasma PYY and enteroglucagon concentrations (Gi/M993, 34(9), 1219). Agents that increase ileal and colonic bile acid or bile salt concentrations will increase gut peptide secretion including, but not limited to, GLP-1 and PYY.

Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver then undergo conjugation of the carboxylic acid with the amine functionality of taurine and glycine. Conjugated bile acids are secreted into the gall bladder where accumulation occurs until a meal is consumed. Upon eating, the gall bladder contracts and empties its contents into the duodenum, where the conjugated bile acids facilitate absorption of cholesterol, fat, and fat-soluble vitamins in the proximal small intestine (For reviews see: Frontiers in Bioscience 2009, 74, 2584; Clinical Pharmacokinetics 2002,

41(10), 751 ; Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2001 , 32, 407). Conjugated bile acids continue to flow through the small intestine until the distal ileum where 90% are reabsorbed into enterocytes via the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT, also known as iBAT). The remaining 10% are deconjugated to bile acids by intestinal bacteria in the terminal ileum and colon of which 5% are then passively reabsorbed in the colon and the remaining 5% being excreted in feces. Bile acids that are reabsorbed by ASBT in the ileum are then transported into the portal vein for recirculation to the liver. This highly regulated process, called enterohepatic recirculation, is important for the body’s overall maintenance of the total bile acid pool as the amount of bile acid that is synthesized in the liver is equivalent to the amount of bile acids that are excreted in feces.

Pharmacological disruption of bile acid reabsorption with an inhibitor of ASBT leads to increased concentrations of bile acids in the colon and feces, a physiological consequence being increased conversion of hepatic cholesterol to bile acids to compensate for fecal loss of bile acids. Many pharmaceutical companies have pursued this mechanism as a strategy for lowering serum cholesterol in patients with dyslipidemia/hypercholesterolemia (For a review see: Current Medicinal Chemistry 2006, 73, 997). Importantly, ASBT-inhibitor mediated increase in colonic bile acid/salt concentration also will increase intestinal GLP-1 , PYY, GLP-2, and other gut peptide hormone secretion. Thus, inhibitors of ASBT could be useful for treatment of type 2 diabetes, type 1 diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity, short bowel syndrome, Chronic Idiopathic Constipation, Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease, and arthritis.

Certain 1 ,4-thiazepines are disclosed, for example in WO 94/18183 and WO 96/05188. These compounds are said to be useful as ileal bile acid reuptake inhibitors (ASBT).

Patent publication WO 201 1/137,135 dislcoses, among other compounds, the following compound. This patent publication also discloses methods of synthesis of the compound.

The preparation of the above compound is also disclosed in J. Med. Chem, Vol 56, pp5094-51 14 (2013).

PATENT

WO 2016020785

EXAMPLES

Patent publication WO 201 1/137,135 dislcoses general methods for preparing the compound. In addition, a detailed synthesis of the compound is disclosed in Example 26. J. Med. Chem, Vol 56, pp5094-51 14 (2013) also discloses a method for synthesising the compound.

The present invention discloses an improved synthesis of the compound.

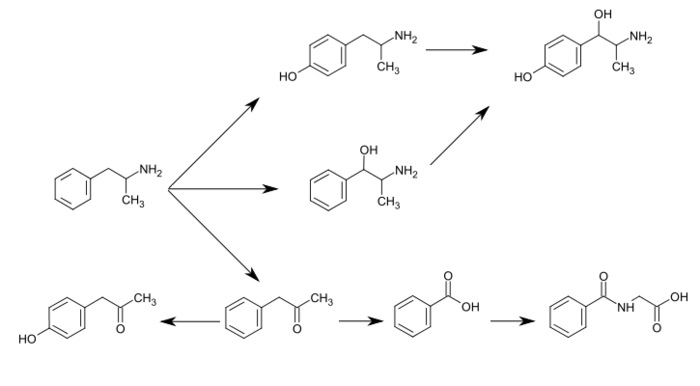

The synthetic scheme of the present invention is depicted in Scheme 1 .

Treatment of 2-methoxyphenyl acetate with sulfur monochloride followed by ester hydrolysis and reduction with zinc gave rise to thiophenol (A). Epoxide ring opening of (+)-2-butyl-ethyloxirane with thiophenol (A) and subsequent treatment of tertiary alcohol (B) with chloroacetonitrile under acidic conditions gave chloroacetamide (C), which was then converted to intermediate (E) by cleavage of the chloroacetamide with thiourea followed by classical resolution with dibenzoyl-L-tartaric acid.

Benzoylation of intermediate (E) with triflic acid and benzoyl chloride afforded intermediate (H). Cyclization of intermediate (H) followed by oxidation of the sulfide to a sulphone, subseguent imine reduction and classical resolution with (+)-camphorsulfonic acid provided intermediate (G), which was then converted to intermediate (H). Intermediate (H) was converted to the target compound using the methods disclosed in Patent publication WO 201 1/137,135.

Scheme 1

![]()

Dibenzoyl-L-tataric acid

![]()

![]()

The present invention also discloses an alternative method for construction of the quaternary chiral center as depicted in Scheme 2. Reaction of intermediate (A) with (R)-2-ammonio-2-ethylhexyl sulfate (K) followed by formation of di-p-toluoyl-L-tartrate salt furnished intermediate (L).

![]()

The present invention also discloses an alternative synthesis of intermediate (H) as illustrated in Scheme 3. Acid catalyzed cyclization of intermediate (F) followed by triflation gave imine (M), which underwent asymmetric reduction with catalyst lr(COD)2BArF and ligand (N) to give intermediate (O). Oxidation of the sulfide in intermediate (O) gave sulphone intermediate (H).

![]()

The present invention differs from the synthesis disclosed in WO 201 1/137,135 and J. Med. Chem, Vol56, pp5094-51 14 (2013) in that intermediate (H) in the present invention is prepared via a new, shorter and more cost-efficient synthesis while the synthesis of the target compound from intermediate (H) remains unchanged.

Intermediate A: 3-Hydroxy-4-methoxythiophenol

![]()

A reaction vessel was charged with 2-methoxyphenyl acetate (60 g, 0.36 mol), zinc chloride (49.2 g, 0.36 mol) and DME (600 mL). The mixture was stirred and S2CI2 (53.6 g, 0.40 mol) was added. The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 2 h. Concentrated HCI (135.4 mL, 1 .63 mol) was diluted with water (60 mL) and added slowly to the rxn mixture, maintaining the temperature below 60 °C. The mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 2 h and then cooled to ambient

temperature. Zinc dust (56.7 g, 0.87 mol) was added in portions, maintaining the temperature below 60 °C. The mixture was stirred at 20-60 °C for 1 h and then concentrated under vacuum to -300 mL. MTBE (1 .2 L) and water (180 mL) were added and the mixture was stirred for 10 min. The layers were separated and the organic layer was washed twice with water (2x 240 mL). The layers were separated and the organic layer was concentrated under vacuum to give an oil. The oil was distilled at 1 10-1 15 °C/2 mbar to give the title compound (42 g, 75%) as colorless oil, which solidified on standing to afford the title compound as a white solid. M.P. 41 -42 °C. 1 H NMR (500 MHz, CDCI3)$ ppm 3.39 (s, 1 H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 5.65 (br. S, 1 H), 6.75 (d, J – 8.3 Hz, 1 H), 6.84 (ddd, J – 8.3, 2.2, 0.6 Hz, 1 H), 6.94 (d, J – 2.2 Hz).

Intermediate E: (R)-5-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-2-methoxyphenol, dibenzoyl-L-tartrate salt

![]()

A reaction vessel was charged with 3-hydroxy-4-methoxythiophenol (5.0 g, 25.2 mmol), (+)-2-butyl-2-ethyloxirane (3.56 g, 27.7 mmol) and EtOH (30 mL). The mixture was treated with a solution of NaOH (2.22 g, 55.5 mmol) in water (20 mL), heated to 40 °C and stirred at 40 °C for 5 h. The mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, treated with toluene (25 mL) and stirred for 10 min. The layers were separated and the organic layer was discarded. The aqueous layer was neutralized with 2N HCI (27.8 mL, 55.6 mmol) and extracted with toluene (100 mL). The organic layer was washed with water (25 mL), concentrated in vacuo to give an oil. The oil was treated with chloroacetonitrile (35.9 mL) and HOAc (4.3 mL) and cooled to 0 °C. H2SO4 (6.7 mL, 126 mmol, pre-diluted with 2.3 mL of water) was added at a rate maintaining the temperature below 10 °C. After stirred at 0 °C for 0.5 h, the reaction mixture was treated with 20% aqueous Na2CO3 solution to adjust the pH to

7-8 and then extracted with MTBE (70 ml_). The extract was washed with water (35 ml_) and concentrated in vacuo to give an oil. The oil was then dissolved in EOH (50 ml_) and treated with HOAc (10 ml_) and thiourea (2.30 g, 30.2 mmol). The mixture was heated at reflux overnight and then cooled to ambient temperature. The solids were filtered and washed with EtOH (10 ml_). The filtrate and the wash were combined and concentrated in vacuo, treated with MTBE (140 ml_) and washed successively with 10% aqueous Na2C03 and water. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo to give an oil. The oil was dissolved in MeCN (72 ml_), heated to -50 °C and then dibenzoyl-L-tartaric acid (9.0 g, 25.2 mmol) in acetonitrile (22 ml_) was added slowly. Seed crystals were added at -50 °C. The resultant slurry was stirred at 45-50 °C for 5 h, then cooled down to ambient temperature and stirred at ambient temperature overnight. The solids were filtered and washed with MeCN (2x 22 ml_). The wet cake was treated with MeCN (150 ml_) and heated to 50 °C. The slurry was stirred at 50 °C for 5 h, cooled over 1 h to ambient temperature and stirred at ambient temperature overnight. The solids were collected by filtration, washed with MeCN (2 x 20 ml_), dried under vacuum to give the title compound (5.5 g, 34% overall yield, 99.5% purity, 93.9% ee) as a white solid. 1 H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 0.78 (m, 6H), 1 .13 (m, 4H), 1 .51 (m, 2H), 1 .58 (q, J – 7.7 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (s, 2H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 5.66 (s, 2H), 6.88 (m, 2H), 6.93 (m, 1 H), 7.49 (m, 4H), 7.63 (m, 2H), 7.94 (m, 4H). EI-LCMS m/z 284 (M++1 of free base).

Intermediate F: (R)-(2-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-4-hydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)(phenyl)methanone

![]()

A suspension of (R)-5-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-2-methoxyphenol, dibenzoyl-L-tartrate salt (29 g, 45.2 mmol) in DCM (435 mL) was treated with water (1 16 mL) and 10% aqueous Na2C03 solution (1 16 mL). The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature until all solids were dissolved (30 min). The layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with water (2 x 60 mL), concentrated under vacuum to give (R)-5-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-2-methoxyphenol (free base) as an off-white solid (13.0 g, quantitative). A vessel was charged with TfOH (4.68 ml, 52.9 mmol) and DCM (30 mL) and the mixture was cooled to 0 °C. 5 g (17.6 mmol) of (R)-5-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-2-methoxyphenol (free base) was dissolved in DCM (10 mL) and added at a rate maintaining the temperature below 10 °C. Benzoyl chloride (4.5 mL, 38.8 mmol) was added at a rate maintaining the temperature below 10 °C. The mixture was then heated to reflux and stirred at reflux for 48 h. The mixture was cooled to 30 °C. Water (20 mL) was added and the mixture was concentrated to remove DCM. EtOH (10 mL) was added. The mixture was heated to 40 ° C, treated with 50% aqueous NaOH solution (10 mL) and stirred at 55 °C. After 1 h, the mixture was cooled to ambient temperature and the pH was adjusted to 6-7 with cone. HCI. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo to remove EtOH. EtOAc (100 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred for 5 min and the layers were separated. The organic layer was washed successively with 10% aqueous Na2CO3 (25 mL) and water (25 mL) and then concentrated in vacuo. The resultant oil was treated with DCM (15 mL). The resultant thick slurry was further diluted with DCM (15 mL) followed by addition of Hexanes (60 mL). The slurry was stirred for 5 min, filtered, washed with DCM/hexanes (1 :2, 2 x 10 mL) and dried under vacuum to give the title compound (7.67 g, 80%) as a yellow solid. 1 NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ ppm 0.70 (t, 7.1 Hz, 3 H), 0.81 (t, 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1 .04-1 .27 (m, 8H), 2.74 (s, 2H), 3.73 (s, 3H), 6.91 (s, 1 H), 7.01 (s, 1 H), 7.52 (dd, J – 7.8, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H). EI-LCMS m/z 388 (M++1 ).

Intermediate G: (3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-8-hydroxy-7-methoxy-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydrobenzo[f][1 ,4]thiazepine 1 ,1 -dioxide, (+)-camphorsulfonate salt

![]()

A vessel was charged with (R)-(2-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-4-hydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)(phenyl)methanone (1 .4 g, 3.61 mmol), toluene (8.4 ml_) and citric acid (0.035 g, 0.181 mmol, 5 mol%). The mixture was heated to reflux overnight with a Dean-Stark trap to remove water. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure to remove solvents. Methanol (14.0 ml_) and oxone (2.22 g, 3.61 mmol, 1 .0 equiv) were added. The mixture was stirred at gentle reflux for 2 h. The mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, and filtered to remove solids. The filter cake was washed with small amount of Methanol. The filtrate was cooled to 5 °C, and treated with sodium borohydride (0.410 g, 10.84 mmol, 3.0 equiv.) in small portions. The mixture was stirred at 5 °C for 2 h and then concentrated to remove the majority of solvents. The mixture was quenched with Water (28.0 ml_) and extracted with EtOAc (28.0 ml_). The organic layer was washed with brine, and then concentrated to remove solvents. The residue was dissolved in MeCN (14.0 ml_) and concentrated again to remove solvents. The residue was dissolved in MeCN (7.00 ml_) and MTBE (7.00 ml_) at 40 °C, and treated with (+)-camphorsulfonic acid (0.839 g, 3.61 mmol, 1 .0 equiv.) at 40 °C for 30 min. The mixture was cooled to ambient temperature, stirred for 2 h, and filtered to collect solids. The filter cake was washed with MTBE/MeCN (2:1 , 3 ml_), and dried at 50 °C to give the title compound (0.75 g, 32% overall yield, 98.6 purity, 97% de, 99.7% ee) as white solids. 1 NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) δ ppm 0.63 (s, 3H), 0.88 (t, J – 6.9 Hz, 3H), 0.97 (m, 6H), 1 .29-1 .39 (m, 5H), 1 .80-1 .97 (m, 6H), 2.08-2.10 (m, 1 H), 2.27 (d, J – 17.3 Hz, 1 H), 2.38-2.44 (m, 3H), 2.54 (b, 1 H), 2.91 (b, 1 H), 3.48 (d, J – 15.4 Hz, 1 H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 4.05 (d, J – 17.2 Hz, 1 H), 6.45 (s, 1 H), 6.56 (s, 1 H), 7.51 -7.56 (m, 4H), 7.68 (s, 1 H), 7.79 (b, 2H), 1 1 .46 (b, 1 H). EI-LCMS m/z 404 (M++1 of free base).

Intermediate H: (3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-methoxy-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2, 3,4,5-tetrahydrobenzo[f][1 ,4]thiazepin-8-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate

![]()

Method 1 : A mixture of (3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-8-hydroxy-7-methoxy-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydrobenzo[f][1 ,4]thiazepine 1 ,1 -dioxide, (+)-camphorsulfonate salt (0.5 g, 0.786 mmol), EtOAc (5.0 mL), and 10% of Na2C03 aqueuous solution (5 mL) was stirred for 15 min. The layers were separated and the aqueous layer was discarded. The organic layer was washed with dilute brine twice, concentrated to remove solvents. EtOAc (5.0 mL) was added and the mixture was concentrated to give a pale yellow solid free base. 1 ,4-Dioxane (5.0 mL) and pyridine (0.13 mL, 1 .57 mmol) were added. The mixture was cooled to 5-10 °C and triflic anhydride (0.199 mL, 1 .180 mmol) was added while maintaining the temperature below 15 °C. The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature until completion deemed by HPLC (1 h). Toluene (5 mL) and water (5 mL) were added. Layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with water, concentrated to remove solvents. Toluene (1 .0 mL) was added to dissolve the residue followed by Isooctane (4.0 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt overnight. The solids was filtered, washed with Isooctane (4.0 mL) to give the title compound (0.34 g, 81 %) as slightly yellow solids. 1 NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) δ ppm 0.86 (t, J – 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.94 (t, J – 7.6 Hz, 3H), 1 .12-1 .15 (m, 1 H), 1 .22-1 .36 (m, 3H), 1 .48-1 .60 (m, 2H), 1 .86-1 .93 (m, 2H), 2.22 (dt, J = 4.1 Hz, 12 Hz, 1 H), 3.10 (d, J – 14.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.49 (d, J – 14.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 6.1 1 (s, 1 H), 6.36 (s, 1 H), 7.38-7.48 (m, 5), 7.98 (s, 1 H).

Method 2: A mixture of (R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-methoxy-5-phenyl-2,3-dihydrobenzo[f][1 ,4]thiazepin-8-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate (0.5 g, 0.997 mmol), ligand (N) (0.078 g, 0.1 10 mmol) and lr(COD)2BArF (0.127 g, 0.100 mmol) in DCM (10.0 mL) was purged with nitrogen three times, then hydrogen three times. The mixture was shaken in Parr shaker under 10 Bar of H2 for 24 h. The experiment described above was repeated with 1 .0 g (1 .994 mmol) input of (R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-methoxy-5-phenyl-2,3-dihydrobenzo[f][1 ,4]thiazepin-8-yl

trifluoromethanesulfonate. The two batches of the reaction mixture were combined,

concentrated to remove solvents, and purified by silica gel chromatography

(hexanes:EtOAc =9:1 ) to give the sulfide (O) as slightly yellow oil (0.6 g, 40% yield, 99.7% purity). The oil (0.6 g, 1 .191 mmol) was dissolved in TFA (1 .836 mL, 23.83 mmol) and stirred at 40 °C. H202 (0.268 mL, 2.62 mmol) was added slowly over 30 min. The mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 2 h and then cooled to room temperature. Water (10 mL) and toluene (6.0 mL) were added. Layers were separated and the organic layer was washed successively with aqueous sodium carbonate solution and wate, and concentrated to dryness. Toluene (6.0 mL) was added and the mixture was concentrated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in toluene (2.4 mL) and isooctane (7.20 mL) was added. The mixture was heated to reflux and then cooled to room temperature. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The solid was filtered and washed with isooctane to give the title compound (0.48 g, 75%).

Intermediate L: (R)-5-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-2-methoxyphenol, di-p-toluoyl-L-tartrate salt

![]()

To a mixture of (R)-2-amino-2-ethylhexyl hydrogen sulfate (1 1 .1 g, 49.3 mmol) in water (23.1 mL) was added NaOH (5.91 g, 148 mmol). The mixture was stirred at reflux for 2 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and extracted with MTBE (30.8 mL). The extract was washed with brine (22 mL), concentrated under vacuum and treated with methanol (30.8 mL). The mixture was stirred under nitrogen and treated with 3-hydroxy-4-methoxythiophenol (7.70 g, 49.3 mmol). The mixture was stirred under nitrogen at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was concentrated under vacuum, treated with acetonitrile (154 mL) and then heated to 45 °C. To the stirred mixture was added (2R,3R)-2,3-bis((4-methylbenzoyl)oxy)succinic acid (19.03 g, 49.3 mmol). The resultant slurry was

stirred at 45 °C. After 2 h, the slurry was cooled to room temperature and stirred for 5 h. The solids were filtered, washed twice with acetonitrile (30 mL) and dried to give the title compound (28.0 g, 85%) as white solids. 1 NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 0.70-0.75 (m, 6H), 1 .17 (b, 4H), 1 .46-1 .55 (m, 4H), 2.30 (s, 6H), 3.71 (s, 3H), 5.58 (s, 2H), 6.84 (s, 2H), 6.89 (s, 1 H), 7.24 (d, J – 1 1 .6 Hz, 4H), 7.76 (d, J – 1 1 .6 Hz, 4H).

Intermediate M: (R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-methoxy-5-phenyl-2,3

dihydrobenzo[f][1 ,4]thiazepin-8-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate

![]()

A flask was charged with (R)-(2-((2-amino-2-ethylhexyl)thio)-4-hydroxy-5-methoxyphenyl)(phenyl)methanone (3.5 g, 9.03 mmol), citric acid (0.434 g, 2.258 mmol), 1 ,4-Dioxane (17.50 mL) and Toluene (17.50 mL). The mixture was heated to reflux with a Dean-Stark trap to distill water azetropically. The mixture was refluxed for 20 h and then cooled to room temperature. EtOAc (35.0 mL) and water (35.0 mL) were added and layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with aqueous sodium carbonate solution and concentrated to remove solvents to give crude imine as brown oil. The oil was dissolved in EtOAc (35.0 mL) and cooled to 0-5 °C. To the mixture was added triethylamine (1 .888 mL, 13.55 mmol) followed by slow addition of Tf2O (1 .831 mL, 10.84 mmol) at 0-5 °C. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Water was added and layers were separated. The organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under vacuum. The crude triflate was purified by silica gel chromatography

(hexane:EtOAc =90:10) to give the title compound (3.4 g, 75%) as amber oil. 1 NMR (400 MHz, CDCI3) δ ppm 0.86 (t, J – 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.92 (t, J – 7.9 Hz, 3H), 1 .19-1 .34 (m, 4H), 1 .47-1 .71 (m, 4H), 3.25 (s, 2H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 6.75 (s, 1 H), 7.35-7.43 (m, 3H), 7.48 (s, 1 H), 7.54 (d, J – 7.6 Hz, 2H).

PAPER

Journal of Medicinal Chemistry (2013), 56(12), 5094-5114.

![Abstract Image]()

The apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT) transports bile salts from the lumen of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to the liver via the portal vein. Multiple pharmaceutical companies have exploited the physiological link between ASBT and hepatic cholesterol metabolism, which led to the clinical investigation of ASBT inhibitors as lipid-lowering agents. While modest lipid effects were demonstrated, the potential utility of ASBT inhibitors for treatment of type 2 diabetes has been relatively unexplored. We initiated a lead optimization effort that focused on the identification of a potent, nonabsorbable ASBT inhibitor starting from the first-generation inhibitor 264W94 (1). Extensive SAR studies culminated in the discovery of GSK2330672 (56) as a highly potent, nonabsorbable ASBT inhibitor which lowers glucose in an animal model of type 2 diabetes and shows excellent developability properties for evaluating the potential therapeutic utility of a nonabsorbable ASBT inhibitor for treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes.

PATENT

WO 2011137135

Example 26: 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl- 2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid

![Figure imgf000082_0001]()

Method 1 , Step 1 : To a solution of (3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-5- phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepine-8-carbaldehyde 1 ,1 -dioxide (683 mg, 1 .644 mmol) in 1 ,2-dichloroethane (20 mL) was added diethyl 3- aminopentanedioate (501 mg, 2.465 mmol) and acetic acid (0.188 mL, 3.29 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 hr then treated with NaHB(OAc)3 (697 mg, 3.29 mmol). The reaction mixture was then stirred at room temperature overnight and quenched with aqueous potassium carbonate solution. The mixture was extracted with DCM. The combined organic layers were washed with H2O, saturated brine, dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give diethyl 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5- phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioate (880 mg, 88%) as a light yellow oil: MS-LCMS m/z 603 (M+H)+.

Method 1 , Step 2: To a solution of diethyl 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7- (methyloxy)-l ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8- yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioate (880 mg, 1 .460 mmol) in a 1 :1 :1 mixture of

THF/MeOH/H2O (30 mL) was added lithium hydroxide (175 mg, 7.30 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight then concentrated under reduced pressure. H2O and MeCN was added to dissolve the residue. The solution was acidified with acetic acid to pH 4-5, partially concentrated to remove MeCN under reduced pressure, and left to stand for 30 min. The white precipitate was collected by filtration and dried under reduced pressure at 50°C overnight to give the title compound (803 mg, 100%) as a white solid: 1 H NMR (MeOH-d4) δ ppm 8.05 (s, 1 H), 7.27 – 7.49 (m, 5H), 6.29 (s, 1 H), 6.06 (s, 1 H), 4.25 (s, 2H), 3.60 – 3.68 (m, 1 H), 3.58 (s, 3H), 3.47 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.09 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.52 – 2.73 (m, 4H), 2.12 – 2.27 (m, 1 H), 1 .69 – 1 .84 (m, 1 H), 1 .48 – 1 .63 (m, 1 H), 1 .05 – 1 .48 (m, 5H), 0.87 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 0.78 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); ES-LCMS m/z 547 (M+H) Method 2: A solution of dimethyl 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-

1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8- yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioate (~ 600 g) in THF (2.5 L) and MeOH (1 .25 L) was cooled in an ice-bath and a solution of NaOH (206 g, 5.15 mol) in water (2.5 L) was added dropwise over 20 min (10-22°C reaction temperature). After stirring 20 min, the solution was concentrated (to remove THF/MeOH) and acidified to pH~4 with concentrated HCI. The precipitated product was aged with stirring, collected by filtration and air dried overnight. A second 600g batch of dimethyl 3-({[(3R,5R)-3- butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4- benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioate was saponified in a similar fashion. The combined crude products (~2 mol theoretical) were suspended in CH3CN (8 L) and water (4 L) and the stirred mixture was heated to 65°C. A solution formed which was cooled to 10°C over 2 h while seeding a few times with an authentic sample of the desired crystalline product. The resulting slurry was stirred at 10°C for 2 h, and the solid was collected by filtration. The filter cake was washed with water and air-dried overnight. Further drying to constant weight in a vacuum oven at 55°C afforded crystalline 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 – dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8- yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid as a white solid (790 g).

Method 3: (3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro- 1 ,4-benzothiazepine-8-carbaldehyde 1 ,1 -dioxide (1802 grams, 4.336 moles) and dimethyl 3-aminopentanedioate (1334 grams, 5.671 moles) were slurried in iPrOAc (13.83 kgs). A nitrogen atmosphere was applied to the reactor. To the slurry at 20°C was added glacial acetic acid (847 ml_, 14.810 moles), and the mixture was stirred until complete dissolution was observed. Solid sodium triacetoxyborohydride (1424 grams, 6.719 moles) was next added to the reaction over a period of 7 minutes. The reaction was held at 20°C for a total of 3 hours at which time LC analysis of a sample indicated complete consumption of the (3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl- 7-(methyloxy)-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepine-8-carbaldehyde 1 ,1 – dioxide. Next, water (20.36 kgs) and brine (4.8 kgs) were added to the reactor. The contents of the reactor were stirred for 10 minutes and then settled for 10 minutes. The bottom, aqueous layer was then removed and sent to waste. A previously prepared, 10% (wt/wt) aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate (22.5 L) was added to the reactor. The contents were stirred for 10 minutes and then settled for 10 minutes. The bottom, aqueous layer was then removed and sent to waste. To the reactor was added a second wash of 10% (wt/wt) aqueous, sodium bicarbonate

(22.5 L). The contents of the reactor were stirred for 10 minutes and settled for 10 minutes. The bottom, aqueous layer was then removed and sent to waste. The contents of the reactor were then reduced to an oil under vacuum distillation. To the oil was added THF (7.15 kgs) and MeOH (3.68 kgs). The contents of the reactor were heated to 55°C and agitated vigorously until complete dissolution was observed. The contents of the reactor were then cooled to 25°C whereupon a previously prepared aqueous solution of NaOH [6.75 kgs of water and 2.09 kgs of NaOH (50% wt wt solution)] was added with cooling being applied to the jacket. The contents of the reactor were kept below 42°C during the addition of the NaOH solution. The temperature was readjusted to 25°C after the NaOH addition, and the reaction was stirred for 75 minutes before HPLC analysis indicated the reaction was complete. Heptane (7.66 kgs) was added to the reactor, and the contents were stirred for 10 minutes and then allowed to settle for 10 minutes. The aqueous layer was collected in a clean nalgene carboy. The heptane layer was removed from the reactor and sent to waste. The aqueous solution was then returned to the reactor, and the reactor was prepared for vacuum distillation. Approximately 8.5 liters of distillate was collected during the vacuum distillation. The vacuum was released from the reactor, and the temperature of the contents was readjusted to 25°C. A 1 N HCI solution (30.76 kgs) was added to the reactor over a period of 40 minutes. The resulting slurry was stirred at 25°C for 10 hours then cooled to 5°C over a period of 2 hours. The slurry was held at 5°C for 4 hours before the product was collected in a filter crock by vacuum filtration. The filter cake was then washed with cold (5°C) water (6 kgs). The product cake was air dried in the filter crock under vacuum for approximately 72 hours. The product was then transferred to three drying trays and dried in a vacuum oven at 50°C for 79 hours. The temperature of the vacuum oven was then raised to 65°C for 85 additional hours. The product was off-loaded as a single batch to give 2568 grams (93.4% yield) of intermediate grade 3-({[(3R,5R)-3- butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4- benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid as an off-white solid.

Intermediate grade 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5- phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid was dissolved (4690 g) in a mixture of glacial acetic acid (8850 g) and purified water (4200 g) at 70°C. The resulting solution was transferred through a 5 micron polishing filter while maintaining the temperature above 30°C. The reactor and filter were rinsed through with a mixture of glacial acetic acid (980 g) and purified water (470 g). The solution temperature was adjusted to 50°C. Filtered purified water (4230 g) was added to the solution. The cloudy solution was then seeded with crystalline 3-({[(3 5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3 ,4,5- tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid (10 g). While maintaining the temperature at 50°C, filtered purified water was charged to the slurry at a controlled rate (1 1030 g over 130 minutes). Additional filtered purified water was then added to the slurry at a faster controlled rate (20740 g over 100 minutes). A final charge of filtered purified water (3780 g) was made to the slurry. The slurry was then cooled to 10°C at a linear rate over 135 minutes. The solids were filtered over sharkskin filter paper to remove the mother liquor. The cake was then rinsed with filtered ethyl acetate (17280 g) then the wash liquors were removed by filtration. The resulting wetcake was isolated into trays and dried under vacuum at 50°C for 23 hours. The temperature was then increased to 60°C and drying was continued for an additional 24 hours to afford crystalline 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl- 7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8- yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid (3740 g, 79.7% yield) as a white solid.

To a slurry of this crystalline 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 – dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8- yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid (3660 g) and filtered purified water (3.6 L) was added filtered glacial acetic acid (7530 g). The temperature was increased to 60°C and full dissolution was observed. The temperature was reduced to 55°C, filtered, and treated with purified water (3.2 L). The solution was then seeded with crystalline 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl-2,3,4,5- tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid (18 g) to afford a slurry. Filtered purified water was charged to the slurry at a controlled rate (9 L over 140 minutes). Additional filtered purified water was then added to the slurry at a faster controlled rate (18 L over 190 minutes). The slurry was then cooled to

10°C at a linear rate over 225 minutes. The solids were filtered over sharkskin filter paper to remove the mother liquor. The cake was then rinsed with filtered purified water (18 L), and the wash liquors were removed by filtration. The resulting wetcake was isolated into trays and dried under vacuum at 60°C for 18.5 hours to afford a crystalline 3-({[(3R,5R)-3-butyl-3-ethyl-7-(methyloxy)-1 ,1 -dioxido-5-phenyl- 2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1 ,4-benzothiazepin-8-yl]methyl}amino)pentanedioic acid (3330 g, 90.8% yield) as a white solid which was analyzed for crystallinity as summarized below.

Paper

Cowan, D. J.; Collins, J. L.; Mitchell, M. B.; Ray, J. A.; Sutton, P. W.; Sarjeant, A. A.; Boros, E. E.Enzymatic- and Iridium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis of a Benzothiazepinylphosphonate Bile Acid Transporter Inhibitor J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78 ( 24) 12726– 12734, DOI: 10.1021/jo402311e

A synthesis of the benzothiazepine phosphonic acid 3, employing both enzymatic and transition metal catalysis, is described. The quaternary chiral center of 3 was obtained by resolution of ethyl (2-ethyl)norleucinate (4) with porcine liver esterase (PLE) immobilized on Sepabeads. The resulting (R)-amino acid (5) was converted in two steps to aminosulfate 7, which was used for construction of the benzothiazepine ring. Benzophenone 15, prepared in four steps from trimethylhydroquinone 11, enabled sequential incorporation of phosphorus (Arbuzov chemistry) and sulfur (Pd(0)-catalyzed thiol coupling) leading to mercaptan intermediate 18. S-Alkylation of 18 with aminosulfate 7 followed by cyclodehydration afforded dihydrobenzothiazepine 20. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of 20 with the complex of [Ir(COD)2BArF] (26) and Taniaphos ligand P afforded the (3R,5R)-tetrahydrobenzothiazepine 30 following flash chromatography. Oxidation of 30 to sulfone 31 and phosphonate hydrolysis completed the synthesis of 3 in 12 steps and 13% overall yield.

Paper

Scheme 1. Current Route to Chiral Intermediate 4 in the Synthesis of GSK2330672

Development of an Enzymatic Process for the Production of (R)-2-Butyl-2-ethyloxirane

Gheorghe-Doru Roiban*† ![]() , Peter W. Sutton*‡, Rebecca Splain§, Christopher Morgan§, Andrew Fosberry∥, Katherine Honicker⊥, Paul Homes∥, Cyril Boudet#, Alison Dann#, Jiasheng Guo§, Kristin K. Brown∇, Leigh Anne F. Ihnken⊥, and Douglas Fuerst⊥

, Peter W. Sutton*‡, Rebecca Splain§, Christopher Morgan§, Andrew Fosberry∥, Katherine Honicker⊥, Paul Homes∥, Cyril Boudet#, Alison Dann#, Jiasheng Guo§, Kristin K. Brown∇, Leigh Anne F. Ihnken⊥, and Douglas Fuerst⊥

†Synthetic Biochemistry, Advanced Manufacturing Technologies, ‡API Chemistry, ∥Protein and Cellular Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Medicines Research Centre, Gunnels Wood Road, Stevenage SG1 2NY, United Kingdom

§API Chemistry, ⊥Synthetic Biochemistry, Advanced Manufacturing Technologies, GlaxoSmithKline, 709 Swedeland Road, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania 19406, United States

# Biotechnology and Environmental Shared Service, Global Manufacturing and Supply, GlaxoSmithKline, Dominion Way, Worthing BN14 8PB, United Kingdom

∇ Molecular Design, Computational and Modeling Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, 1250 S. Collegeville Road, Collegeville, Pennsylvania 19426, United States

Org. Process Res. Dev., Article ASAP

DOI: 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00179

An epoxide resolution process was rapidly developed that allowed access to multigram scale quantities of (R)-2-butyl-2-ethyloxirane 2 at greater than 300 g/L reaction concentration using an easy-to-handle and store lyophilized powder of epoxide hydrolase from Agromyces mediolanus. The enzyme was successfully fermented on a 35 L scale and stability increased by downstream processing. Halohydrin dehalogenases also gave highly enantioselective resolution but were shown to favor hydrolysis of the (R)-2 epoxide, whereas epoxide hydrolase from Aspergillus nigerinstead provided (R)-7 via an unoptimized, enantioconvergent process.

REFERENCES

1: Nunez DJ, Yao X, Lin J, Walker A, Zuo P, Webster L, Krug-Gourley S, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Gillmor DS, Johnson SL. Glucose and lipid effects of the ileal apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor GSK2330672: double-blind randomized trials with type 2 diabetes subjects taking metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016 Jul;18(7):654-62. doi: 10.1111/dom.12656. Epub 2016 Apr 21. PubMed PMID: 26939572.

2: Wu Y, Aquino CJ, Cowan DJ, Anderson DL, Ambroso JL, Bishop MJ, Boros EE, Chen L, Cunningham A, Dobbins RL, Feldman PL, Harston LT, Kaldor IW, Klein R, Liang X, McIntyre MS, Merrill CL, Patterson KM, Prescott JS, Ray JS, Roller SG, Yao X, Young A, Yuen J, Collins JL. Discovery of a highly potent, nonabsorbable apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor (GSK2330672) for treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Chem. 2013 Jun 27;56(12):5094-114. doi: 10.1021/jm400459m. Epub 2013 Jun 6. PubMed PMID: 23678871.

///////GSK 2330672, phase 2

CCCC[C@@]1(CS(=O)(=O)c2cc(c(cc2[C@H](N1)c3ccccc3)OC)CNC(CC(=O)O)CC(=O)O)CC

Filed under:

Phase2 drugs Tagged:

GSK 2330672,

phase 2 ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()