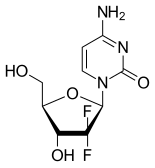

GEMCITABINE

95058-81-4

WeightAverage: 263.1981

Monoisotopic: 263.071762265

Chemical FormulaC9H11F2N3O4

4-amino-1-[(2R,4R,5R)-3,3-difluoro-4-hydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-2-one

Product Ingredients

| INGREDIENT | UNII | CAS | INCHI KEY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemcitabine hydrochloride | U347PV74IL | 122111-03-9 | OKKDEIYWILRZIA-OSZBKLCCSA-N |

- LY-188011

- LY188011

Gemcitabine

CAS Registry Number: 95058-81-4

CAS Name: 2¢-Deoxy-2¢,2¢-difluorocytidine

Additional Names: 1-(2-oxo-4-amino-1,2-dihydropyrimidin-1-yl)-2-deoxy-2,2-difluororibose; dFdC; dFdCyd

Manufacturers’ Codes: LY-188011

Trademarks: Gemzar (Lilly)

Molecular Formula: C9H11F2N3O4

Molecular Weight: 263.20

Percent Composition: C 41.07%, H 4.21%, F 14.44%, N 15.97%, O 24.32%

Literature References: Prepn: L. W. Hertel, GB2136425; idem,US4808614 (1984, 1989 both to Lilly); L. W. Hertel et al.,J. Org. Chem.53, 2406 (1988); T. S. Chou et al.,Synthesis1992, 565. Antitumor activity: L. W. Hertel et al.,Cancer Res.50, 4417 (1990). Mode of action study: V. W. T. Ruiz et al.,Biochem. Pharmacol.46, 762 (1993). Clinical pharmacokinetics and toxicity: J. L. Abbruzzese et al.,J. Clin. Oncol.9, 491 (1991). Review of clinical studies: B. Lund et al.,Cancer Treat. Rev.19, 45-55 (1993).

Properties: Crystals from water, pH 8.5. [a]365 +425.36°; [a]D +71.51° (c = 0.96 in methanol). uv max (ethanol): 234, 268 (e 7810, 8560). LD10 i.v. in rats: 200 mg/m2 (Abbruzzese).

Optical Rotation: [a]365 +425.36°; [a]D +71.51°

Absorption maximum: uv max (ethanol): 234, 268 (e 7810, 8560)

Toxicity data: LD10 i.v. in rats: 200 mg/m2 (Abbruzzese)

Derivative Type: Hydrochloride

CAS Registry Number: 122111-03-9

Molecular Formula: C9H11F2N3O4.HCl

Molecular Weight: 299.66

Percent Composition: C 36.07%, H 4.04%, F 12.68%, N 14.02%, O 21.36%, Cl 11.83%

Properties: Crystals from water-acetone, mp 287-292° (dec). [a]D +48°; [a]365 +257.9° (c = 1.0 in deuterated water). uv max (water): 232, 268 nm (e 7960, 9360).

Melting point: mp 287-292° (dec)

Optical Rotation: [a]D +48°; [a]365 +257.9° (c = 1.0 in deuterated water)

Absorption maximum: uv max (water): 232, 268 nm (e 7960, 9360)

Therap-Cat: Antineoplastic.

Keywords: Antineoplastic; Antimetabolites; Pyrimidine Analogs.

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside metabolic inhibitor used as adjunct therapy in the treatment of certain types of ovarian cancer, non-small cell lung carcinoma, metastatic breast cancer, and as a single agent for pancreatic cancer.

Gemcitabine hydrochloride was first approved in ZA on Jan 10, 1995, then approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on May 15, 1996, and approved by Pharmaceuticals and Medicals Devices Agency of Japan (PMDA) on Aug 31, 2001. It was developed and marketed as Gemzar® by Eli Lilly.

Gemcitabine hydrochloride is a nucleoside metabolic inhibitor. It kills cells undergoing DNA synthesis and blocks the progression of cells through the G1/S-phase boundary. It is indicated for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer that has relapsed at least 6 months after completion of platinum-based therapy, in combination with paclitaxel, for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer after failure of prior anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy, unless anthracyclines were clinically contraindicated, and it is also indicated in combination with cisplatin for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer, and treated as a single agent for the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Gemzar® is available as injection of lyophilized powder for intravenous use, containing 200 mg or 1000 mg of free Gemcitabine per vial. The recommended initial dosage is 1000 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on days 1 and 8 of each 21 day cycle for ovarian cancer, 1250 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on days 1 and 8 of each 21 day cycle for breast cancer, 1000 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28 day cycle or 1250 mg/m2 over 30 minutes on days 1 and 8 of each 21 day cycle for non-small cell lung cancer, and 1000 mg/m2 over 30 minutes once weekly for the first 7 weeks, then one week rest, then once weekly for 3 weeks of each 28 day cycle for pancreatic cancer.

Approved Countries or AreaUpdate US, JP, CN, ZA

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996-05-15 | First approval | Gemzar | Ovarian cancer,Breast cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),Pancreatic cancer | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For solution | Eq. 200 mg/1000 mg Gemcitabine/vial | Lilly | Priority |

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013-02-01 | New indication | Gemzar | Relapsed or refractory malignant lymphoma | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For solution | 200 mg; 1 g | Lilly | |

| 2011-02-23 | New indication | Gemzar | Advanced ovarian cancer | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For solution | 200 mg; 1 g | Lilly | |

| 2010-02-05 | New indication | Gemzar | Advanced breast cancer | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For solution | 200 mg; 1 g | Lilly | |

| 2008-11-25 | New indication | Gemzar | Urothelial cancer | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For solution | 200 mg; 1 g | Lilly | |

| 2006-06-15 | New indication | Gemzar | Biliary cancer | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For solution | 200 mg; 1 g | Lilly | |

| 2001-08-31 | First approval | Gemzar | Pancreatic cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For suspension | 200 mg; 1 g | Lilly |

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014-04-15 | Marketing approval | Ovarian cancer,Breast cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),Pancreatic cancer | Injection | Eq. 1000 mg Gemcitabine per vial | 湖北一半天制药 | ||

| 2014-04-15 | Marketing approval | Ovarian cancer,Breast cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),Pancreatic cancer | Injection | Eq. 200 mg Gemcitabine per vial | 湖北一半天制药 | 6类 | |

| 2014-04-08 | Marketing approval | Ovarian cancer,Breast cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),Pancreatic cancer | Injection | Eq.1000 mg Gemcitabine per vial | 南京正大天晴制药 | 6类 | |

| 2011-12-02 | Marketing approval | 健择/Gemzar | Ovarian cancer,Breast cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),Pancreatic cancer | Injection | Eq. 200 mg/1000 mg Gemcitabine per vial | Lilly | |

| 2010-08-31 | Marketing approval | Ovarian cancer,Breast cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),Pancreatic cancer | Injection | 1000 mg/200 mg | 北京协和药厂 | 6类 |

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995-01-10 | First approval | Gemzar | Ovarian cancer,Breast cancer,Non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),Pancreatic cancer | Injection, Lyophilized powder, For solution | Eq. 200 mg/1000 mg Gemcitabine per vial | Lilly |

Gemcitabine, with brand names including Gemzar,[1] is a chemotherapy medication.[2] It treats cancers including testicular cancer,[3]breast cancer, ovarian cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and bladder cancer.[2][4] It is administered by intravenous infusion.[2] It acts against neoplastic growth, and it inhibits the replication of Orthohepevirus A, the causative agent of Hepatitis E, through upregulation of interferon signaling.[5]

Common side effects include bone marrow suppression, liver and kidney problems, nausea, fever, rash, shortness of breath, mouth sores, diarrhea, neuropathy, and hair loss.[2] Use during pregnancy will likely result in fetal harm.[2] Gemcitabine is in the nucleoside analog family of medication.[2] It works by blocking the creation of new DNA, which results in cell death.[2]

Gemcitabine was patented in 1983 and was approved for medical use in 1995.[6] Generic versions were introduced in Europe in 2009 and in the US in 2010.[7][8] It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines.[9]

Medical uses

Gemcitabine treats various carcinomas. It is used as a first-line treatment alone for pancreatic cancer, and in combination with cisplatin for advanced or metastatic bladder cancer and advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. It is used as a second-line treatment in combination with carboplatin for ovarian cancer and in combination with paclitaxel for breast cancer that is metastatic or cannot be surgically removed.[10][11][12]

It is commonly used off-label to treat cholangiocarcinoma[13] and other biliary tract cancers.[14]

It is given by intravenous infusion at a chemotherapy clinic.[2]

Contraindications and interactions

Taking gemcitabine can also affect fertility in men and women, sex life, and menstruation. Women taking gemcitabine should not become pregnant, and pregnant and breastfeeding women should not take it.[15]

As of 2014, drug interactions had not been studied.[11][10]

SYN

. Hertel, L. W.; Kroin, J. S.; Misner, J. W.; Tustin, J. M. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 2406– 2409.

NEXT

a) Noe, C. R.; Jasic, M.; Kollmann, H.; Saadat, K. WO009147, 2007.; b) Noe, C. R.; Jasic, M.; Kollmann, H.; Saadat, K. US0249119, 2008. Note: no stereochemistry was indica

NExT

15. Hanzawa, Y.; Inazawa, K.; Kon, A.; Aoki, H.; Kobayashi, Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 659–662. 16. Wirth, D. D. EP0727432, 1996

Synthesis Reference

John A. Weigel, “Process for making gemcitabine hydrochloride.” U.S. Patent US6001994, issued May, 1995.US6001994Route 1

Reference:1. J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53, 2406-2409.

2. US4808614A.Route 2

Reference:1. CN102417533A.Route 3

Reference:1. Nucleosides, Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids 2010, 29, 113-122.Route 4

Reference:1. CN102617677A.Route 5

Reference:1. CN103012527A.

SYN

U.S. Patent No. 4,808,614 (the ‘614 patent) describes a process for synthetically producing gemcitabine, which process is generally illustrated in Scheme Scheme 1

5

SYN

U.S. Patent No. 4,965,374 (the ‘374 patent) describes a process for producing gemcitabine from an intermediate 3,5-dibenzoyl ribo protected lactone of the formula:

11 where the desired erythro isomer can be isolated in a crystalline form from a mixture of erythro and threo isomers. The process described in the ‘374 patent is generally outlined in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2

mixture of α and β anomers

SYN

U.S. Patent No. 5,521,294 (the ‘294 patent) describes l-alkylsulfonyl-2,2- difluoro-3 -carbamoyl ribose intermediates and intermediate nucleosides derived therefrom. The compounds are reportedly useful in the preparation of 2′-deoxy-2′,2’- difluoro-β-cytidine and other β-anomer nucleosides. The ‘294 patent teaches, inter alia, that the 3-hydroxy carbamoyl group on the difluororibose intermediate may enhance formation of the desired β-anomer nucleoside derivative. The ‘294 patent describes converting the lactone 4 to the dibenzoyl mesylate 13, followed by deprotection at the 3 position to obtain the 5-monobenzoyl mesylate intermediate 15, which is reacted with various isocyanates to obtain the compounds of formula 16. The next steps involve coupling and deprotection using methods similar to those described in previous patents. The process and the intermediates 15 and 16 are illustrated by scheme 3 below: Scheme 3

13 15

PhCOCK

PhNCO/TEA -o. -~- j*«0Ms

PhNHCOO -r F

16

1 coupling 2 deprotection

16 gemcitabine

CLIP

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0008621514000500

PATENT

https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2008129530A1/en

Scheme 4

e3

13A deprotection isomer separation

deprotection

EXAMPLE 1

[0045] This example demonstrates the preparation of 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D- ribofuranose-3,5-dicinnamate-l-p-toluenesulfonate.

[0046] Crude 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-riboufuranose-3,5-dicinnamate (2.5g, 6 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (20 ml) in a round flask, and diethylamine (0.7g, 9.6 mmol) was added followed by p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (1.32 g, 6.92 mmol), which was added drop wise while cooling to 0-50C. The mixture was stirred for 1 hour, and washed with IN HCl (15 ml), concentrated solution OfNaHCO3 (15 ml), and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was distilled off under reduced pressure to obtain crude 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribofuranose-3,5-dicinnamate-l-p- toluenesulfonate as light oil. Yield: 3.22 g, (5.6 mmol), 93%.

EXAMPLE 2

[0047] This example demonstrates the preparation of 3′,5′-dicinnamoyl-2′-deoxy- 2′,2′-difluorocytidine.

[0048] Dry 1 ,2-dichloroethane (800 ml) was added to N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)- cytosine (136 g, 487 mmol) under nitrogen blanket to produce a clear solution, followed by adding trimethylsilyl triflate (Me3SiOTf), (100 ml, 122.8 g, 520 mmol) and stirred for 30 minutes. A solution of 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribofuranose-3,5- dicinnamate-1-p-toluenesulfonate (128 g, 224 mmol) in 1 ,2-dichloroethane (400 ml) was added drop wise, and the mixture was refluxed overnight. After cooling, the solvent was distilled off to obtain crude 3,5-dicinnamoyl-N4-trimethylsilyl-2′-deoxy- 2′,2′-difluorocytidine as a light yellow solid. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (1600 ml) and washed 3 times with water (3X400 ml). The ethyl acetate phase was mixed with concentrated solution OfNaHCO3 (800 ml) for about 5 minutes, and then the mixture was set aside for about 20 minutes without stirring. The thus formed solid, which was precipitated in the inter-phase of the two layers, was filtered off and washed with 60 ml of ethyl acetate. The solid was dried under reduced pressure to obtain 116.7 g (223 mmol, 99.5%) of the crude 3′,5′-dicinnamoyl- 2′-deoxy-2′,2′- difluorocytidine containing 73.3 % of the β-anomer and 11.8 % of the α-anomer.

EXAMPLE 3

[0049] This example demonstrates the preparation of 3′,5′-dicinnamoyl-2′-deoxy- 2′,2′-difluorocytidine.

[0050] Dry 1,2-dichloroethane (1.5 L) was added to bis(trimethylsilyl)cytosine (417 g, 1.49 mol) under nitrogen blanket to produce a clear solution followed by adding trimethylsilyl triflate (Me3SiOTf), (300 ml, 368.4 g, 1.56 mol) and stirred for 30 minutes. A solution of 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribofuranose-3,5-dicinnamate-l-p- toluenesulfonate (384 g, 673 mmol) in 1,2-dichloroethane (1.2 L) was added drop wise, and the mixture was refluxed overnight. After cooling, the solvent was distilled off to obtain crude 3,5-dicinnamoyl-N4-trimethylsilyl-2l-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine as a light yellow solid. The residue was dissolved in ethyl acetate (2.4 L) and washed 3 times with water (3X1.2 L). The ethyl acetate phase was mixed with concentrated solution OfNaHCO3 (1.34 L) for about 20 minutes. The thus formed solid, which was precipitated in the inter-phase of the two layers, was filtered off and washed with 180 ml of ethyl acetate. The solid was dried under reduced pressure to obtain 346.5 g (0.66 mol, 99.9% yield) of the crude 3l,5l-dicinnamoyl-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine containing 43 % of the β-anomer and 52 % of the α-anomer.

EXAMPLE 4

[0051] This example demonstrates the preparation of gemcitabine hydrochloride. [0052] To a solution of ammonia-methanol (15.8 %, 4.57 L), the crude 3,5- dicirmamoyl-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine of example 3 was added (346.5 g, 0.66 mol), and stirred at ambient temperature for 6 hours. The mixture was concentrated to afford a light yellow solid (306 g). Purified water (3 L) was added to the solid, followed by addition of ethyl acetate (1.8 L), and stirring was maintained for about 10 minutes. The aqueous layer was separated and the organic layer was extracted with water (1.05 L). The aqueous layers were combined and water was removed by evaporation under reduced pressure to obtain an oil (154.7 g). Water was added (660 ml) and the mixture was heated to 50-550C to dissolve the solid. The mixture was cooled to 5-1O0C during about one hour and mixed for about 16 hours at that temperature. The thus formed solid was filtered and dried to afford 46.75 g (0.177 mol), containing 98 % of the β-anomer and 1.3 % of the α-anomer. 0.5N HCl (936 ml) was added followed by addition of dichloromethane (300 ml) with stirring. The water phase was separated and the aqueous phase was washed with dichloromethane (300 ml). After filtration, the aqueous phase was concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure to obtain gemcitabine hydrochloride as a solid (46.9 g). The solid was dissolved in water (187 ml) at ambient temperature and the mixture was heated to 500C to afford a clear solution and cooled to ambient temperature. Acetone (1.4 L) was added and stirring was maintained for about one hour. Then, the precipitate was collected by filtration and washed twice with acetone (2X30 ml) and dried at 450C under vacuum to obtain 39.2 g of gemcitabine hydrochloride, containing 99.9% of the β-anomer

EXAMPLE 5

[0053] This example demonstrates the preparation of gemcitabine hydrochloride. [0054] To a solution of ammonia-methanol (about 15.8 %, 1.35 L), the crude 3′,5′- dicinnamoyl-2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluorocytidine prepared as described in example 2 was added (96 g, 183.4 mmol), and stirred at ambient temperature for 4 hours. The mixture was concentrated to afford a light yellow solid (80.5 g). Purified water (1 L) was added to the solid, followed by addition of ethyl acetate (600 ml), and stirring was maintained for about 10 minutes. The aqueous layer was separated and the organic layer was extracted with water (350 ml). The aqueous layers were combined and water was removed by evaporation under reduced pressure to obtain an oil (46.4 g). Water was added (220 ml) and the mixture was heated to 50-550C to dissolve the solid. The mixture was cooled to 0-50C during about one hour and mixed for about 16 hours at that temperature. The thus formed solid was filtered and dried to afford 11.1 g of gemcitabine free base. 0.5N HCl (240 ml) was added followed by addition of dichloromethane (100 ml) with stirring. The water phase was separated and the aqueous phase was washed with dichloromethane (300 ml). After filtration, the aqueous phase was concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure to obtain gemcitabine hydrochloride as a solid (12.0 g). The solid was dissolved in water (48 ml) at ambient temperature and the mixture was heated to 5O0C to afford a clear solution and cooled to ambient temperature. Acetone (360 ml) was added and stirring was maintained for about one hour. Then, the precipitate was collected by filtration and washed twice with acetone (2X30 ml) and dried at 450C under vacuum to obtain 9.9 g of gemcitabine hydrochloride, containing 99.6% of the β-anomer.

EXAMPLE 6

[0055] This example demonstrates the slurrying procedure of the 3 ‘,5′- dicinnamoyl-2′-deoxy-2’,2l-difluorocytidine in different solvents. [0056] 1 g of the crude 3′,5′-dicinnamoyl-2′-deoxy-2l,2′-difluorocytidine, containing 73.7 % of the β-anomer and 17.5 % of the α-anomer, was placed in flask and 10 ml of a solvent was added and the mixture was mixed at ambient temperature for one hour. Then, the solid was obtained by filtration, washed with 5 ml of the solvent and dried. The liquid obtained after filtering the solid and the liquid obtained after washing the solid were combined (hereinafter the mother liquor). The ratio between the β-anomer and the α-anomer in the solid and in the mother liquor was determined by HPLC and the results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

/////////

AS ON DEC2021 3,491,869 VIEWS ON BLOG WORLDREACH AVAILABLEFOR YOUR ADVERTISEMENT

join me on Linkedin

Anthony Melvin Crasto Ph.D – India | LinkedIn

join me on Researchgate

RESEARCHGATE

join me on Facebook

Anthony Melvin Crasto Dr. | Facebook

join me on twitter

Anthony Melvin Crasto Dr. | twitter

+919321316780 call whatsaapp

EMAIL. amcrasto@amcrasto

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Adverse effects

Gemcitabine is a chemotherapy drug that works by killing any cells that are dividing.[10] Cancer cells divide rapidly and so are targeted at higher rates by gemcitabine, but many essential cells also divide rapidly, including cells in skin, the scalp, the stomach lining, and bone marrow, resulting in adverse effects.[16]: 265

The gemcitabine label carries warnings that it can suppress bone marrow function and cause loss of white blood cells, loss of platelets, and loss of red blood cells, and that it should be used carefully in people with liver, kidney, or cardiovascular disorders. People taking it should not take live vaccines. The warning label also states it may cause posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, that it may cause capillary leak syndrome, that it may cause severe lung conditions like pulmonary edema, pneumonia, and adult respiratory distress syndrome, and that it may harm sperm.[10][17]

More than 10% of users develop adverse effects, including difficulty breathing, low white and red blood cells counts, low platelet counts, vomiting and nausea, elevated transaminases, rashes and itchy skin, hair loss, blood and protein in urine, flu-like symptoms, and edema.[10][15]

Common adverse effects (occurring in 1–10% of users) include fever, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty sleeping, tiredness, cough, runny nose, diarrhea, mouth and lip sores, sweating, back pain, and muscle pain.[10]

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare but serious side effect that been associated with particular chemotherapy medications including gemcitabine. TTP is a blood disorder and can lead to microangipathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), neurologic abnormalities, fever, and renal disease.[18]

Pharmacology

Gemcitabine is hydrophilic and must be transported into cells via molecular transporters for nucleosides (the most common transporters for gemcitabine are SLC29A1 SLC28A1, and SLC28A3).[19][20] After entering the cell, gemcitabine is first modified by attaching a phosphate to it, and so it becomes gemcitabine monophosphate (dFdCMP).[19][20] This is the rate-determining step that is catalyzed by the enzyme deoxycytidine kinase (DCK).[19][20] Two more phosphates are added by other enzymes. After the attachment of the three phosphates gemcitabine is finally pharmacologically active as gemcitabine triphosphate (dFdCTP).[19] [21]

After being thrice phosphorylated, gemcitabine can masquerade as deoxycytidine triphosphate and is incorporated into new DNA strands being synthesized as the cell replicates.[2][19][20]

When gemcitabine is incorporated into DNA it allows a native, or normal, nucleoside base to be added next to it. This leads to “masked chain termination” because gemcitabine is a “faulty” base, but due to its neighboring native nucleoside it eludes the cell’s normal repair system (base-excision repair). Thus, incorporation of gemcitabine into the cell’s DNA creates an irreparable error that leads to inhibition of further DNA synthesis, and thereby leading to cell death.[2][19][20]

The form of gemcitabine with two phosphates attached (dFdCDP) also has activity; it inhibits the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), which is needed to create new DNA nucleotides. The lack of nucleotides drives the cell to uptake more of the components it needs to make nucleotides from outside the cell, which also increases uptake of gemcitabine.[2][19][20][22]

Chemistry

Gemcitabine is a synthetic pyrimidine nucleoside prodrug—a nucleoside analog in which the hydrogen atoms on the 2′ carbon of deoxycytidine are replaced by fluorine atoms.[2][23][24]

The synthesis described and pictured below is the original synthesis done in the Eli Lilly Company labs. Synthesis begins with enantiopure D-glyceraldehyde (R)-2 as the starting material which can made from D-mannitol in 2–7 steps. Then fluorine is introduced by a “building block” approach using ethyl bromodifluroacetate. Then, Reformatsky reaction under standard conditions will yield a 3:1 anti/syn diastereomeric mixture, with one major product. Separation of the diastereomers is carried out via HPLC, thus yielding the anti-3 gemcitabine in a 65% yield.[23][24] At least two other full synthesis methods have also been developed by different groups.[24]

Illustration of the original synthesis process used and published by Hertel et al. in 1988 of Lilly laboratories.

History[

Gemcitabine was first synthesized in Larry Hertel’s lab at Eli Lilly and Company during the early 1980s. It was intended as an antiviral drug, but preclinical testing showed that it killed leukemia cells in vitro.[25]

During the early 1990s gemcitabine was studied in clinical trials. The pancreatic cancer trials found that gemcitabine increased one-year survival time significantly, and it was approved in the UK in 1995[10] and approved by the FDA in 1996 for pancreatic cancers.[4] In 1998, gemcitabine received FDA approval for treating non-small cell lung cancer and in 2004, it was approved for metastatic breast cancer.[4]

European labels were harmonized by the EMA in 2008.[26]

By 2008, Lilly’s worldwide sales of gemcitabine were about $1.7 billion; at that time its US patents were set to expire in 2013 and its European patents in 2009.[27] The first generic launched in Europe in 2009,[7] and patent challenges were mounted in the US which led to invalidation of a key Lilly patent on its method to make the drug.[28][29] Generic companies started selling the drug in the US in 2010 when the patent on the chemical itself expired.[29][8] Patent litigation in China made headlines there and was resolved in 2010.[30]

Society and culture

As of 2017, gemcitabine was marketed under many brand names worldwide: Abine, Accogem, Acytabin, Antoril, axigem, Bendacitabin, Biogem, Boligem, Celzar, Citegin, Cytigem, Cytogem, Daplax, DBL, Demozar, Dercin, Emcitab, Enekamub, Eriogem, Fotinex, Gebina, Gemalata, Gembin, Gembine, Gembio, Gemcel, Gemcetin, Gemcibine, Gemcikal, Gemcipen, Gemcired, Gemcirena, Gemcit, Gemcitabin, Gemcitabina, Gemcitabine, Gemcitabinum, Gemcitan, Gemedac, Gemflor, Gemful, Gemita, Gemko, Gemliquid, Gemmis, Gemnil, Gempower, Gemsol, Gemstad, Gemstada, Gemtabine, Gemtavis, Gemtaz, Gemtero, Gemtra, Gemtro, Gemvic, Gemxit, Gemzar, Gentabim, Genuten, Genvir, Geroam, Gestredos, Getanosan, Getmisi, Gezt, Gitrabin, Gramagen, Haxanit, Jemta, Kalbezar, Medigem, Meditabine, Nabigem, Nallian, Oncogem, Oncoril, Pamigeno, Ribozar, Santabin, Sitagem, Symtabin, Yu Jie, Ze Fei, and Zefei.[1]

Research

Because it is clinically valuable and is only useful when delivered intravenously, methods to reformulate it so that it can be given by mouth have been a subject of research.[31][32][33]

Research into pharmacogenomics and pharmacogenetics has been ongoing. As of 2014, it was not clear whether or not genetic tests could be useful in guiding dosing and which people respond best to gemcitabine.[19] However, it appears that variation in the expression of proteins (SLC29A1, SLC29A2, SLC28A1, and SLC28A3) used for transport of gemcitabine into the cell lead to variations in its potency. Similarly, the genes that express proteins that lead to its inactivation (deoxycytidine deaminase, cytidine deaminase, and NT5C) and that express its other intracellular targets (RRM1, RRM2, and RRM2B) lead to variations in response to the drug.[19] Research has also been ongoing to understand how mutations in pancreatic cancers themselves determine response to gemcitabine.[34]

It has been studied as a treatment for Kaposi sarcoma, a common cancer in people with AIDS which is uncommon in the developed world but not uncommon in the developing world.[35]

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Gemcitabine International Brands”. Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l “Gemcitabine Hydrochloride”. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ “Drug Formulary/Drugs/ gemcitabine – Provider Monograph”. Cancer Care Ontario. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c National Cancer Institute (2006-10-05). “FDA Approval for Gemcitabine Hydrochloride”. National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Li Y, Li P, Li Y, Zhang R, Yu P, Ma Z, Kainov DE, de Man RA, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q (December 2020). “Drug screening identified gemcitabine inhibiting hepatitis E virus by inducing interferon-like response via activation of STAT1 phosphorylation”. Antiviral Research. 184: 104967. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104967. PMID 33137361.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 511. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Myers, Calisha (13 March 2009). “Gemcitabine from Actavis launched on patent expiry in EU markets”. FierceBiotech. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Press release: Hospira launches two-gram vial of gemcitabine hydrochloride for injection”. Hospira via News-Medical.Net. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g “UK label”. UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 5 June 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “US formLabel” (PDF). FDA. June 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 020509 Archived 2017-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zhang XW, Ma YX, Sun Y, Cao YB, Li Q, Xu CA (June 2017). “Gemcitabine in Combination with a Second Cytotoxic Agent in the First-Line Treatment of Locally Advanced or Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”. Targeted Oncology. 12 (3): 309–321. doi:10.1007/s11523-017-0486-5. PMID 28353074. S2CID 3833614.

- ^ Plentz RR, Malek NP (December 2016). “Systemic Therapy of Cholangiocarcinoma”. Visceral Medicine. 32 (6): 427–430. doi:10.1159/000453084. PMC 5290432. PMID 28229078.

- ^ Jain A, Kwong LN, Javle M (November 2016). “Genomic Profiling of Biliary Tract Cancers and Implications for Clinical Practice”. Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 17 (11): 58. doi:10.1007/s11864-016-0432-2. PMID 27658789. S2CID 25477593.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Macmillan Cancer Support. “Gemcitabine”. Macmillan Cancer Support. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Rachel Airley (2009). Cancer Chemotherapy. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-09254-5.

- ^ Siddall E, Khatri M, Radhakrishnan J (July 2017). “Capillary leak syndrome: etiologies, pathophysiology, and management”. Kidney International. 92 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.11.029. PMID 28318633.

- ^ Kasi PM (January 2011). “Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and gemcitabine”. Case Reports in Oncology. 4 (1): 143–8. doi:10.1159/000326801. PMC 3114619. PMID 21691573.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Alvarellos ML, Lamba J, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, Wang L, Klein DJ, Altman RB, Klein TE (November 2014). “PharmGKB summary: gemcitabine pathway”. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 24 (11): 564–74. doi:10.1097/fpc.0000000000000086. PMC 4189987. PMID 25162786.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Mini E, Nobili S, Caciagli B, Landini I, Mazzei T (May 2006). “Cellular pharmacology of gemcitabine”. Annals of Oncology. 17 Suppl 5: v7-12. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdj941. PMID 16807468.

- ^ Fatima, M., Iqbal Ahmed, M. M., Batool, F., Riaz, A., Ali, M., Munch-Petersen, B., & Mutahir, Z. (2019). Recombinant deoxyribonucleoside kinase from Drosophila melanogaster can improve gemcitabine based combined gene/chemotherapy for targeting cancer cells. Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, 19(4), 342-349. https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2019.4136

- ^ Cerqueira NM, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ (2007). “Understanding ribonucleotide reductase inactivation by gemcitabine”. Chemistry. 13 (30): 8507–15. doi:10.1002/chem.200700260. PMID 17636467.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brown K, Weymouth-Wilson A, Linclau B (April 2015). “A linear synthesis of gemcitabine”. Carbohydrate Research. 406: 71–5. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2015.01.001. PMID 25681996.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Brown K, Dixey M, Weymouth-Wilson A, Linclau B (March 2014). “The synthesis of gemcitabine”. Carbohydrate Research. 387: 59–73. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2014.01.024. PMID 24636495.

- ^ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug discovery: a history. New York: Wiley. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ^ “Gemzar”. European Medicines Agency. 24 September 2008. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ Myers, Calisha (18 August 2009). “Patent for Lilly’s cancer drug Gemzar invalidated”. FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ Holman, Christopher M. (Summer 2011). “Unpredictability in Patent Law and Its Effect on Pharmaceutical Innovation” (PDF). Missouri Law Review. 76 (3): 645–693. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ravicher, Daniel B. (28 July 2010). “On the Generic Gemzar Patent Fight”. Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012.

- ^ Wang M, Alexandre D (2015). “Analysis of Cases on Pharmaceutical Patent Infringement in Great China”. In Rader RR, et al. (eds.). Law, Politics and Revenue Extraction on Intellectual Property. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 9781443879262. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ^ Dyawanapelly S, Kumar A, Chourasia MK (2017). “Lessons Learned from Gemcitabine: Impact of Therapeutic Carrier Systems and Gemcitabine’s Drug Conjugates on Cancer Therapy”. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems. 34 (1): 63–96. doi:10.1615/CritRevTherDrugCarrierSyst.2017017912. PMID 28322141.

- ^ Birhanu G, Javar HA, Seyedjafari E, Zandi-Karimi A (April 2017). “Nanotechnology for delivery of gemcitabine to treat pancreatic cancer”. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 88: 635–643. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.071. PMID 28142120.

- ^ Dubey RD, Saneja A, Gupta PK, Gupta PN (October 2016). “Recent advances in drug delivery strategies for improved therapeutic efficacy of gemcitabine”. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 93: 147–62. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2016.08.021. PMID 27531553.

- ^ Pishvaian MJ, Brody JR (March 2017). “Therapeutic Implications of Molecular Subtyping for Pancreatic Cancer”. Oncology. 31 (3): 159–66, 168. PMID 28299752. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017.

- ^ Krown SE (September 2011). “Treatment strategies for Kaposi sarcoma in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities”. Current Opinion in Oncology. 23 (5): 463–8. doi:10.1097/cco.0b013e328349428d. PMC 3465839. PMID 21681092.

External links

- “Gemcitabine”. Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /dʒɛmˈsaɪtəbiːn/ |

| Trade names | Gemzar, others[1] |

| Other names | 2′, 2′-difluoro 2’deoxycytidine, dFdC |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category | AU: D |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | L01BC05 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | AU: S4 (Prescription only)UK: POM (Prescription only)US: ℞-onlyIn general: ℞ (Prescription only) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | <10% |

| Elimination half-life | Short infusions: 32–94 minutes Long infusions: 245–638 minutes |

| Identifiers | |

| showIUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 95058-81-4 |

| PubChem CID | 60750 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 4793 |

| DrugBank | DB00441 |

| ChemSpider | 54753 |

| UNII | B76N6SBZ8R |

| KEGG | D02368 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:175901 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL888 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID3040487 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.124.343 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H11F2N3O4 |

| Molar mass | 263.201 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | Interactive image |

| showSMILES | |

| showInChI | |

| (verify) |

/////////////GEMCITABINE, LY 188011, LY188011, CANCER

NC1=NC(=O)N(C=C1)[C@@H]1O[C@H](CO)[C@@H](O)C1(F)F

Patent

Publication numberPriority datePublication dateAssigneeTitle

EP0577303A1 *1992-06-221994-01-05Eli Lilly And CompanyStereoselective glycosylation process

WO2006070985A1 *2004-12-302006-07-06Hanmi Pharm. Co., Ltd.METHOD FOR THE PREPARATION OF 2#-DEOXY-2#,2#-DIFLUOROCYTIDINE

WO2007027564A2 *2005-08-292007-03-08Chemagis Ltd.Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

WO2007069838A1 *2005-12-142007-06-21Dong-A Pharm.Co., Ltd.A manufacturing process of 2′,2′-difluoronucleoside and intermediate

Family To Family Citations

JPS541315B2 *1974-11-221979-01-23

US4526988A *1983-03-101985-07-02Eli Lilly And CompanyDifluoro antivirals and intermediate therefor

US4751221A *1985-10-181988-06-14Sloan-Kettering Institute For Cancer Research2-fluoro-arabinofuranosyl purine nucleosides

US5223608A *1987-08-281993-06-29Eli Lilly And CompanyProcess for and intermediates of 2′,2′-difluoronucleosides

US4965374A *1987-08-281990-10-23Eli Lilly And CompanyProcess for and intermediates of 2′,2′-difluoronucleosides

US5256798A *1992-06-221993-10-26Eli Lilly And CompanyProcess for preparing alpha-anomer enriched 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribofuranosyl sulfonates

US5371210A *1992-06-221994-12-06Eli Lilly And CompanyStereoselective fusion glycosylation process for preparing 2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluoronucleosides and 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoronucleosides

US5256797A *1992-06-221993-10-26Eli Lilly And CompanyProcess for separating 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-D-ribofuranosyl alkylsulfonate anomers

US5480992A *1993-09-161996-01-02Eli Lilly And CompanyAnomeric fluororibosyl amines

US5521294A *1995-01-181996-05-28Eli Lilly And Company2,2-difluoro-3-carbamoyl ribose sulfonate compounds and process for the preparation of beta nucleosides

US5559222A *1995-02-031996-09-24Eli Lilly And CompanyPreparation of 1-(2′-deoxy-2′,2′-difluoro-D-ribo-pentofuranosyl)-cytosine from 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-β-D-ribo-pentopyranose

US5602262A *1995-02-031997-02-11Eli Lilly And CompanyProcess for the preparation of 2-deoxy-2,2-difluoro-β-D-ribo-pentopyranose

US5633367A *1995-03-241997-05-27Eli Lilly And CompanyProcess for the preparation of a 2-substituted 3,3-difluorofuran

GB9514268D0 *1995-07-131995-09-13Hoffmann La RochePyrimidine nucleoside

US5756775A *1995-12-131998-05-26Eli Lilly And CompanyProcess to make α,α-difluoro-β-hydroxyl thiol esters

CA2641719A1 *2006-02-072007-08-16Chemagis Ltd.Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

US20070249823A1 *2006-04-202007-10-25Chemagis Ltd.Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

Publication numberPriority datePublication dateAssigneeTitle

CN102617483A *2011-06-302012-08-01江苏豪森药业股份有限公司Process for recycling cytosine during preparing process of gemcitabine hydrochloride

WO2013164798A12012-05-042013-11-07Tpresso AgPackaging of dry leaves in sealed capsules

CN105566418A *2014-10-092016-05-11江苏笃诚医药科技股份有限公司2′,3′-di-O-acetyl-5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine synthesis method

EP3817732A4 *2018-08-032022-06-08Cellix Bio Private LimitedCompositions and methods for the treatment of cancer

Family To Family Citations

CA2641719A1 *2006-02-072007-08-16Chemagis Ltd.Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

US20070249823A1 *2006-04-202007-10-25Chemagis Ltd.Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

IT1393062B1 *2008-10-232012-04-11Prime Europ TherapeuticalsPROCEDURE FOR THE PREPARATION OF GEMCITABINE CHLORIDRATE

PublicationPublication DateTitle

CA2509687C2012-08-14Process for the production of 2'-branched nucleosides

WO2008129530A12008-10-30Gemcitabine production process

AU2005328519B22012-03-01Intermediate and process for preparing of beta- anomer enriched 21deoxy, 21 ,21-difluoro-D-ribofuranosyl nucleosides

EP1931693A22008-06-18Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

EP2164856A12010-03-24Processes related to making capecitabine

US8193354B22012-06-05Process for preparation of Gemcitabine hydrochloride

EP3638685A12020-04-22Synthesis of 3'-deoxyadenosine-5'-0-[phenyl(benzyloxy-l-alaninyl)]phosphate (nuc-7738)

EP2456778A12012-05-30Process for producing flurocytidine derivatives

US20090221811A12009-09-03Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

JP5114556B22013-01-09A novel highly stereoselective synthetic process and intermediate for gemcitabine

EP0350292B11994-05-04Process for preparing 2'-deoxy-beta-adenosine

KR100908363B12009-07-20Stereoselective preparation method of tri-O-acetyl-5-deoxy-β-D-ribofuranose and separation method thereof

US20070249823A12007-10-25Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

WO2007070804A22007-06-21Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

KR101259648B12013-05-09A manufacturing process of 2′,2′-difluoronucloside and intermediate

US8338586B22012-12-25Process of making cladribine

WO2010029574A22010-03-18An improved process for the preparation of gemcitabine and its intermediates using novel protecting groups and ion exchange resins

KR20080090950A2008-10-09Process for preparing gemcitabine and associated intermediates

WO2012115578A12012-08-30Synthesis of flg