Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate, ナルメフェン塩酸塩水和物

2019/1/8, PMDA, JAPAN, Selincro,

In January 2019, Otsuka received regulatory approval in Japan

Antialcohol dependence, Narcotic antagonist, Opioid receptor partial agonist/antagonist

Morphinan-3,14-diol, 17-(cyclopropylmethyl)-4,5-epoxy-6-methylene-, hydrochloride, hydrate (1:1:2), (5α)-

| Formula |

C21H25NO3. HCl. 2H2O

|

|---|---|

| CAS |

1228646-70-5

5096-26-9 free form

58895-64-0 (Nalmefene HCl)

|

| Mol weight |

411.9196

|

JF-1; NIH-10365; ORF-11676; SRD-174, Lu-AA36143

APPROVED 1995 USA

Trade Name:Revex® MOA:Opioid receptor antagonist Indication:Respiratory depression

Company:Baxter (Originator)

17- (cyclopropylmethyl)-4,5-alpha-epoxy-6-methylenemorphinan-3,14-diol

(5α)-17-(Cyclopropylmethyl)-4,5-epoxy-6-methylenemorphinan-3,14-diol;

(-)-Nalmefene;

6-Deoxo-6-methylenenaltrexone; 6-Desoxy-6-methylenenaltrexone;

JF 1; Nalmetrene; ORF 11676;

CHINA 2013

| Approval Date | Approval Type | Trade Name | Indication | Dosage Form | Strength | Company | Review Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013-11-13 | Marketing approval | Respiratory depression | Injection | 1 ml:0.1 mg | 灵宝市豫西药业 | 3.1类 | |

| 2013-09-22 | Marketing approval | 抒纳 | Respiratory depression | Injection | 1 ml:0.1 mg(以纳美芬计) | 辽宁海思科制药 | 3.1类 |

| 2013-08-02 | Marketing approval | 乐萌 | Respiratory depression | Injection | 1 ml:0.1 mg | 成都天台山制药 | 3.1类 |

| 2012-12-31 | Marketing approval | Respiratory depression | Injection | 1 ml:0.1 mg (以C21H25NO3计) | 北京四环制药 | ||

| 2012-05-15 | Marketing approval | Respiratory depression | Injection | 1 ml:0.1 mg | 西安利君制药 |

EMA LINK

In February 2013, EC approval in all EU member states was granted for the reduction of alcohol consumption in adults with alcohol dependence

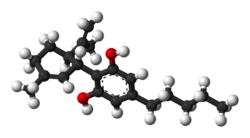

Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate is a white or almost white crystalline powder. The chemical name is 17-(Cyclopropylmethyl)-4,5-α-epoxy-6-methylene-morphinan-3,14-diol hydrochloride dihydrate, has the following molecular formula C21H25NO3 ⋅ HCl ⋅ 2 H2O

Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate is very soluble in water and is not hygroscopic. Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate is a chiral compound, containing 4 asymmetric carbon atoms. Only one crystal form of Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate has been identified. Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate does not melt, but becomes amorphous after dehydration.

The structure of nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate was demonstrated by elemental analysis, IR, UV/Vis, 1 H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectroscopy as well as MS spectrometry. Its crystal structure was analysed by X-ray diffraction and specific optical rotation was determined. It has been shown that no polymorphic forms were observed.

PATENTS AND GENERICS

The original product patent was based on US 03814768 which expired in 1991. However, a number of patents cover formulations and use. Lundbeck and Biotie have a family based on WO 2010063292 which claims novel crystal forms and hydrate salts, in particular Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate, and their use in alcohol dependence. There are European and US patents granted on this EP 02300479 will expire December 2029 and US-08530495 will expire August 2030.

Nalmefene hydrochloride was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on Apr 17, 1995. It was developed and marketed asRevex® by Baxterin in the US.

Nalmefene is an opioid receptor antagonist. It acts as a silent antagonist of the μ-opioid receptor and as a partial agonist of the κ-opioid receptor, it also possesses affinity for the δ-opioid receptor. Revex® is indicated for the complete or partial reversal of opioid drug effects, including respiratory depression, induced by either natural or synthetic opioids. It is also indicated in the management of known or suspected opioid overdose.

Revex® is available as a sterile solution for intravenous, intramuscular and subcutaneous administration in two concentrations, containing 100 μg or 1.0 mg of nalmefene free base per mL. The recommended dose is initiating at 0.25 μg/kg followed by 0.25 μg/kg incremental doses at 2-5 minute intervals for reversal of postoperative opioid depression, stopping as soon as the desired degree of opioid reversal is obtained.

Nalmefene (trade name Selincro), originally known as nalmetrene, is an opioid antagonist used primarily in the management of alcohol dependence. It has also been investigated for the treatment of other addictions such as pathological gambling.[1]

Nalmefene is an opiate derivative similar in both structure and activity to the opioid antagonist naltrexone. Advantages of nalmefene relative to naltrexone include longer half-life, greater oral bioavailability and no observed dose-dependent liver toxicity.[2]

As with other drugs of this type, nalmefene may precipitate acute withdrawal symptoms in patients who are dependent on opioid drugs, or more rarely when used post-operatively, to counteract the effects of strong opioids used in surgery.

Medical uses

Opioid overdose

Intravenous doses of nalmefene have been shown effective at counteracting the respiratory depression produced by opioid overdose.[3]

This is not the usual application for this drug, for two reasons:

- The half-life of nalmefene is longer than that of naloxone. One might have thought this would make it useful for treating overdose involving long-acting opioids: it would require less frequent dosing, and hence reduce the likelihood of renarcotization as the antagonist wears off. But, in fact, the use of nalmefene is not recommended in such situations. Unfortunately, opioid-dependent patients may go home and use excessive doses of opioids in order to overcome nalmefene’s opioid blockade and to relieve the discomfort of opioid withdrawal. Such large doses of opioids may be fatal. This is why naloxone (a shorter-acting drug) is normally a better choice for overdose reversal.[4]

- In addition, injectable nalmefene is no longer available on the market.

When nalmefene is used to treat an opioid overdose, doses of nalmefene greater than 1.5 mg do not appear to give any greater benefit than doses of only 1.5 mg.

Alcohol dependence

Nalmefene is used in Europe to reduce alcohol dependence[5] and NICE recommends the use of nalmefene to reduce alcohol consumption in combination with psychological support for people who drink heavily.[6]

Based on a meta analysis, the usefulness of nalmefene for alcohol dependence is unclear.[7] Nalmefene, in combination with psychosocial management, may decrease the amount of alcohol drunk by people who are alcohol dependent.[7][8] The medication may also be taken “as needed”, when a person feels the urge to consume alcohol.[8]

Side effects

The following adverse effects have been reported with nalmefene:

Very Common (≥1⁄10)[edit]

- Insomnia

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Nausea

Common (≥1⁄100 to <1/10)[edit]

- Decreased appetite

- Sleep disorder

- Confusional state

- Restlessness

- Libido decreased (including loss of libido)

- Somnolence

- Tremor

- Disturbance in attention

- Paraesthesia

- Hypoaesthesia

- Tachycardia

- Palpitations

- Vomiting

- Dry mouth

- Diarrhoea

- Hyperhidrosis

- Muscle spasms

- Fatigue

- Asthenia

- Malaise

- Feeling abnormal

- Weight decreased

The majority of these reactions were mild or moderate, associated with treatment initiation, and of short duration.[9]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Nalmefene acts as a silent antagonist of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) (Ki = 0.24 nM) and as a weak partial agonist (Ki = 0.083 nM; Emax = 20–30%) of the κ-opioid receptor (KOR), with similar affinity for these two receptors but a several-fold preference for the KOR.[10]

[11][12] In vivo evidence indicative of KOR activation, such as elevation of serum prolactin levels due to dopamine suppression and increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axisactivation via enhanced adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol secretion, has been observed in humans and animals.[10][13] Side effects typical of KOR activation such as hallucinations and dissociation have also been observed with nalmefene in human studies.[14] It is thought that the KOR activation of nalmefene might produce dysphoria and anxiety.[15] In addition to MOR and KOR binding, nalmefene also possesses some, albeit far lower affinity for the δ-opioid receptor (DOR) (Ki = 16 nM), where it behaves as an antagonist.[10][12][16]

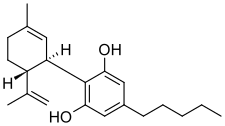

Nalmefene is structurally related to naltrexone and differs from it by substitution of the ketone group at the 6-position of naltrexone with a methylene group (CH2). It binds to the MOR with similar affinity relative to naltrexone, but binds “somewhat more avidly” to the KOR and DOR in comparison.[10][13]

Pharmacokinetics

Nalmefene is extensively metabolized in the liver, mainly by conjugation with glucuronic acid and also by N-dealkylation. Less than 5% of the dose is excreted unchanged. The glucuronide metabolite is entirely inactive, while the N-dealkylated metabolite has minimal pharmacological activity.[citation needed]

Chemistry

Nalmefene is a derivative of naltrexone and was first reported in 1975.[17]

Society and culture

United States

In the US, immediate-release injectable nalmefene was approved in 1995 as an antidote for opioid overdose. It was sold under the trade name Revex. The product was discontinued by its manufacturer around 2008.[18][19] Perhaps, due to its price, it never sold well. (See § Opioid overdose, above.)

Nalmefene in pill form, which is used to treat alcohol dependence and other addictive behaviors, has never been sold in the United States.[2]

Europe

Lundbeck has licensed nalmefene from Biotie Therapies and performed clinical trials with nalmefene for treatment of alcohol dependence.[20] In 2011 they submitted an application for their drug termed Selincro to the European Medicines Agency.[21] The drug was approved for use in the EU in March 2013.[22] and in October 2013 Scotland became the first country in the EU to prescribe the drug for alcohol dependence.[23] England followed Scotland by offering the substance as a treatment for problem drinking in October 2014.[24] In November 2014 nalmefene was appraised and approved as a treatment supplied by Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) for reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence.[25]

Research

Nalmefene is a partial agonist of the κ-opioid receptor and may be useful to treat cocaine addiction.[26]

SYN

Nalmefene (CAS NO.: 55096-26-9), with its systematic name of Morphinan-3,14-diol, 17-(cyclopropylmethyl)-4,5-epoxy-6-methylene-, (5alpha)-, could be produced through many synthetic methods.

Following is one of the synthesis routes:

By a Wittig reaction at naltrexone (I) with triphenylmethylphosphonium bromide (II) in DMSO in the presence of NaH as base.

PAPER

J. Med. Chem. 1975, 18, 259-262

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/jm00237a008

PATENT

WO 2010136039

PATENT

US 3814768

| Mol. Formula: C21H25NO3 |

| Appearance: Off-White to Pale Yellow Solid |

| Melting Point: 182-185˚C |

| Mol. Weight: 339.43 |

Nalmefene (trade name Selincro), originally known as nalmetrene, is an opioid receptor antagonist developed in the early 1970s,[1] and used primarily in the management of alcohol dependence, and also has been investigated for the treatment of other addictions such as pathological gambling and addiction to shopping.

Nalmefene is an opiate derivative similar in both structure and activity to the opiate antagonist naltrexone. Advantages of nalmefene relative to naltrexone include longer half-life, greater oral bioavailability and no observed dose-dependent liver toxicity. As with other drugs of this type, nalmefene can precipitate acute withdrawal symptoms in patients who are dependent on opioid drugs, or more rarely when used post-operatively to counteract the effects of strong opioids used in surgery.

Nalmefene differs from naltrexone by substitution of the ketone group at the 6-position of naltrexone with a methylene group (CH2), which considerably increases binding affinity to the μ-opioid receptor. Nalmefene also has high affinity for the other opioid receptors, and is known as a “universal antagonist” for its ability to block all three.

In clinical trials using this drug, doses used for treating alcoholism were in the range of 20–80 mg per day, orally.[2] The doses tested for treating pathological gambling were between 25–100 mg per day.[3] In both trials, there was little difference in efficacy between the lower and higher dosage regimes, and the lower dose (20 and 25 mg, respectively) was the best tolerated, with similar therapeutic efficacy to the higher doses and less side effects. Nalmefene is thus around twice as potent as naltrexone when used for the treatment of addictions.

Intravenous doses of nalmefene at between 0.5 to 1 milligram have been shown effective at counteracting the respiratory depression produced by opiate overdose,[4] although this is not the usual application for this drug as naloxone is less expensive.

Doses of nalmefene greater than 1.5 mg do not appear to give any greater benefit in this application. Nalmefene’s longer half-life might however make it useful for treating overdose involving longer acting opioids such as methadone, as it would require less frequent dosing and hence reduce the likelihood of renarcotization as the antagonist wears off.

Nalmefene is extensively metabolised in the liver, mainly by conjugation with glucuronic acid and also by N-dealkylation. Less than 5% of the dose is excreted unchanged. The glucuronide metabolite is entirely inactive, while the N-dealkylated metabolite has minimal pharmacological activity.

Lundbeck has licensed the drug from Biotie Therapies and performed clinical trials with nalmefene for treatment of alcohol dependence.[5] In 2011 they submitted an application for their drug termed Selincro to the European Medicines Agency.[6] It has not been available on the US market since at least August 2008.[citation needed]

Side effects

- Common: drowsiness, hypertension, tachycardia, dizziness, nausea, vomiting

- Occasional: fever, hypotension, vasodilatation, chills, headache

- Rare: agitation, arrhythmia, bradycardia, confusion, hallucinations, myoclonus, itching[7]

Properties

- Soluble in water up to 130 mg/mL, soluble in chloroform up to 0.13 mg/mL

- pKa 7.6

- Distribution half-life: 41 minutes

Nalmefene is a known opioid receptor antagonist which can inhibit pharmacological effects of both administered opioid agonists and endogenous agonists deriving from the opioid system. The clinical usefulness of nalmefene as antagonist comes from its ability to promptly (and selectively) reverse the effects of these opioid agonists, including the frequently observed depressions in the central nervous system and the respiratory system.

Nalmefene has primarily been developed as the hydrochloride salt for use in the management of alcohol dependency, where it has shown good effect in doses of 10 to 40 mg taken when the patient experiences a craving for alcohol (Karhuvaara et al, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res., (2007), Vol. 31 No. 7. pp 1179-1187). Additionally, nalmefene has also been investigated for the treatment of other addictions such as pathological gambling and addiction to shopping. In testing the drug in these developmental programs, nalmefene has been used, for example, in the form of parental solution (Revex ).

).

Nalmefene is an opiate derivative quite similar in structure to the opiate antagonist naltrexone. Advantages of nalmefene compared to naltrexone include longer half- life, greater oral bioavailability and no observed dose-dependent liver toxicity. Nalmefene differs structurally from naltrexone in that the ketone group at the 6- position of naltrexone is replaced by a methylene (CH2) group, which considerably increases binding affinity to the μ-opioid receptor. Nalmefene also has high affinity for the other opioid receptors (K and δ receptors) and is known as a “universal antagonist” as a result of its ability to block all three receptor types.

Nalmefene can be produced from naltrexone by the Wittig reaction. The Wittig reaction is a well known method within the art for the synthetic preparation of olefins (Georg Wittig, Ulrich Schόllkopf (1954). “Uber Triphenyl-phosphin- methylene ah olefinbildende Reagenzien I”. Chemische Berichte 87: 1318), and has been widely used in organic synthesis.

The procedure in the Wittig reaction can be divided into two steps. In the first step, a phosphorus ylide is prepared by treating a suitable phosphonium salt with a base. In the second step the ylide is reacted with a substrate containing a carbonyl group to give the desired alkene.

The preparation of nalmefene by the Wittig reaction has previously been disclosed by Hahn and Fishman (J. Med. Chem. 1975, 18, 259-262). In their method, naltrexone is reacted with the ylide methylene triphenylphosphorane, which is prepared by treating methyl triphenylphosphonium bromide with sodium hydride (NaH) in DMSO. An excess of about 60 equivalents of the ylide is employed in the preparation of nalmefene by this procedure.

For industrial application purposes, the method disclosed by Hahn and Fishman has the disadvantage of using a large excess of ylide, such that very large amounts phosphorus by-products have to be removed before nalmefene can be obtained in pure form. Furthermore, the NaH used to prepare the ylide is difficult to handle on an industrial scale as it is highly flammable. The use of NaH in DMSO is also well known by the skilled person to give rise to unwanted runaway reactions. The Wittig reaction procedure described by Hahn and Fishman gives nalmefene in the form of the free base. The free base is finally isolated by chromatography, which may be not ideal for industrial applications.

US 4,535,157 also describes the preparation of nalmefene by use of the Wittig reaction. In the method disclosed therein the preparation of the ylide methylene triphenylphosphorane is carried out by using tetrahydrofuran (THF) as solvent and potassium tert-butoxidc (KO-t-Bu) as base. About 3 equivalents of the ylide are employed in the described procedure.

Although the procedure disclosed in US 4,535,157 avoids the use of NaH and a large amount of ylide, the method still has some drawbacks which limit its applicability on an industrial scale. In particular, the use of THF as solvent in a Wittig reaction is disadvantageous because of the water miscibility of THF. During the aqueous work-up much of the end product (nalmefene) may be lost in the aqueous phases unless multiple re-extractions are performed with a solvent which is not miscible with water.

Furthermore, in the method described in US 4,535,157, multiple purification steps are carried out in order to remove phosphine oxide by-products of the Wittig reaction. These purification steps require huge amounts of solvents, which is both uneconomical and labor extensive requiring when running the reaction on an industrial scale. As in the case of the Wittig reaction procedure described by Hahn and Fishman (see above) the Wittig reaction procedure disclosed in US 4,535,157 also yields nalmefene as the free base, such that an additional step is required to prepare the final pharmaceutical salt form, i.e. the hydrochloride, from the isolated nalmefene base.

US 4,751,307 also describes the preparation of nalmefene by use of the Wittig reaction. Disclosed is a method wherein the synthesis is performed using anisole (methoxybenzene) as solvent and KO-t-Bu as base. About 4 equivalents of the ylide methylene triphenylphosphorane were employed in this reaction. The product was isolated by extraction in water at acidic pHs and then precipitating at basic pHs giving nalmefene as base.

Even though the isolation procedure for nalmefene as free base is simplified, it still has some disadvantages. The inventors of the present invention repeated the method disclosed in US 4,751,307 and found that the removal of phosphine oxide by-products was not efficient. These impurities co-precipitate with the nalmefene during basifϊcation, yielding a product still contaminated with phosphorus byproducts and having, as a consequence, a low chemical purity, as illustrated in example 2 herein.

There is therefore a need within the field to improve the method of producing nalmefene by the Wittig reaction. In particular, there is a need for a method that is readily applicable on a large industrial scale and which avoids the use of water- miscible solvents, such as THF, in the Wittig reaction, and permits easy isolation of nalmefene in a pure form suitable for its transformation to the final pharmaceutical salt form.

………………………………..

http://www.google.com/patents/EP2435439A1?cl=en

present invention the Wittig reaction may be performed by mixing a methyltriphenylphosphonium salt with 2- methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF) and a suitable base to afford the ylide methylene triphenylphosphorane :

Methyltriphenylphosphonium salt Methylene triphenylphosphorane Yhde

The preformed ylide is subsequently reacted ‘in situ’ with naltrexone to give nalmefene and triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO):

Naltrexone Yhde Nalmefene TPPO

Example 1 Methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (MTPPB, 25.8 Kg) was suspended in 2- methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF, 56 litres). Keeping the temperature in the range 20-250C, KO-t-Bu (8.8 kg) was charged in portions under inert atmosphere in one hour. The suspension turned yellow and was stirred further for two hours. An anhydrous solution of naltrexone (8.0 Kg) in MTHF (32 litres) was then added over a period of one hour at 20-250C. The suspension was maintained under stirring for a few hours to complete the reaction. The mixture was then treated with a solution of ammonium chloride (4.2 Kg) in water (30.4 litres) and then further diluted with water (30.4 litres). The phases were separated, the lower aqueous phase was discarded and the organic phase was washed twice with water (16 litres). The organic phase was concentrated to residue under vacuum and then diluted with dichloromethane (40 litres) to give a clear solution. Concentrated aqueous hydrochloric acid (HCl 37%, 2 litres) was added over one hour at 20- 250C. The suspension was stirred for at least three hours at the same temperature, and then filtered and washed with dichloromethane (8 litres) and then with acetone (16 litres). The solid was then re-suspended in dichloromethane (32 litres) at 20-250C for a few hours and then filtered and washed with dichloromethane (16 litres), affording 9.20 Kg of nalmefene hydrochloride, corresponding to 7.76 kg of nalmefene hydrochloride (99.7% pure by HPLC). Molar yield 89%.

HPLC Chromatographic conditions

Column: Zorbax Eclipse XDB C-18, 5 μm, 150 x 4.6 mm or equivalent Mobile Phase A: Acetonitrile / Buffer pH = 2.3 10 / 90

Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile / Buffer pH = 2.3 45 / 55

Buffer: Dissolve 1.1 g of Sodium Octansulfonate in 1 L of water. Adjust the pH to 2.3 with diluted

H3PO4. Column Temperature: 35°C

Detector: UV at 230 nm

Flow: 1.2 ml/min

Injection volume: 10 μl

Time of Analysis: 55 minutes

Example 2

The procedure described in US 4,751,307 was repeated, starting from 1Og of naltrexone and yielding 8.5g of nalmefene. The isolated product showed the presence of phosphine oxides by-products above 15% molar as judged by 1HNMR.

Example 3.

Methyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (MTPPB, 112.9g) was suspended in 2- methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF, 245 ml). Keeping the temperature in the range 20- 25°C, KO-t-Bu (38.7 g) was charged in portions under inert atmosphere in one hour. The suspension was stirred for two hours. An anhydrous solution of naltrexone (35 g) in MTHF (144 ml) was then added over a period of one hour at 20-250C. The suspension was maintained under stirring overnight. The mixture was then treated with a solution of glacial acetic acid (17.7 g) in MTHF. Water was then added and the pH was adjusted to 9-10. The phases were separated, the lower aqueous phase was discarded and the organic phase was washed twice with water. The organic phase was concentrated to residue under vacuum and then diluted with dichloromethane (175 ml) to give a clear solution. Concentrated aqueous hydrochloric acid (HCl 37%, 10. Ig) was added over one hour at 20- 25°C. The suspension was stirred and then filtered and washed with dichloromethane and acetone. The product was dried affording 38.1g of Nalmefene HCl. Example 4

Example 3 was repeated but the Wittig reaction mixture after olefmation completeness was treated with acetone and then with an aqueous solution of ammonium chloride. After phase separation, washings, distillation and dilution with dichloromethane, the product was precipitated as hydrochloride salt using HCl 37%. The solid was filtered and dried affording 37.6 g of Nalmefene HCl.

Example 5 Preparation of Nalmefene HCl dihydrate from Nalmefene HCl Nalmefene HCl (7.67 Kg, purity 99.37%, assay 93.9%) and water (8.6 litres) were charged into a suitable reactor. The suspension was heated up to 800C until the substrate completely dissolved. Vacuum was then applied to remove organic solvents. The resulting solution was filtered through a 0.65 μm cartridge and then diluted with water (2.1 litres) that has been used to rinse the reactor and pipelines. The solution was cooled down to 500C and 7 g of Nalmefene HCl dihydrate seeding material was added. The mixture was cooled to 0-50C over one hour with vigorous stirring and then maintained under stirring for one additional hour. The solid was filtered of and washed with acetone. The wet product was dried at 25°C under vacuum to provide 5.4 Kg of Nalmefene HCl dihydrate (purity 99.89%, KF 8.3% , yield 69%).

………………….

http://www.google.com/patents/EP2316456A1?cl=en

……………………

http://www.google.com/patents/US8598352

A structural analog of Naltrexone (N285780) with opiate antagonist activity used in pharmaceutical treatment of alcoholism. Other pharmacological applications of this compound aim to reduce food cravings, drug abuse and pulmonary disease in affected individuals. Used as an opioid-induced tranquilizer on large animals in the veterinary industry. Narcotic antagonist.

|

References

- ^ NCT00132119 ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Jump up to:a b See: “Drug Record: Nalmefene”. LiverTox. National Library of Medicine. 24 March 2016.

- ^ Label information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration“Archived copy” (PDF). Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved 2014-11-07.

- ^ Based on: Stephens, Everett. “Opioid Toxicity Medication » Medication Summary”. Medscape. WebMD LLC.

- ^ “Selincro 18mg film-coated tablets”. UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. September 2016.

- ^ “Technology appraisal guidance [TA325]: Nalmefene for reducing alcohol consumption in people with alcohol dependence”. NICE. 26 November 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Palpacuer, C; Laviolle, B; Boussageon, R; Reymann, JM; Bellissant, E; Naudet, F (December 2015). “Risks and benefits of nalmefene in the treatment of adult alcohol dependence: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished double-blind randomized controlled trials”. PLOS Medicine. 12 (12): e1001924. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001924. PMC 4687857. PMID 26694529.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Paille, François; Martini, Hervé (2014). “Nalmefene: a new approach to the treatment of alcohol dependence”. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 5 (5): 87–94. doi:10.2147/sar.s45666. PMC 4133028. PMID 25187751.

- ^ “Selincro”. European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Bart, G; Schluger, JH; Borg, L; Ho, A; Bidlack, JM; Kreek, MJ (December 2005). “Nalmefene induced elevation in serum prolactin in normal human volunteers: partial kappa opioid agonist activity?” (PDF). Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (12): 2254–62. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300811. PMID 15988468.

- ^ Bart G, Schluger JH, Borg L, Ho A, Bidlack JM, Kreek MJ (2005). “Nalmefene induced elevation in serum prolactin in normal human volunteers: partial kappa opioid agonist activity?”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (12): 2254–62. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300811. PMID 15988468.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Linda P. Dwoskin (29 January 2014). Emerging Targets & Therapeutics in the Treatment of Psychostimulant Abuse. Elsevier Science. pp. 398–. ISBN 978-0-12-420177-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Niciu, Mark J.; Arias, Albert J. (2013). “Targeted opioid receptor antagonists in the treatment of alcohol use disorders”. CNS Drugs. 27 (10): 777–787. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0096-4. ISSN 1172-7047. PMC 4600601. PMID 23881605.

- ^ “Nalmefene (new drug) Alcohol dependence: no advance”. Prescrire International. 23(150): 150–152. 2014. PMID 25121147. (subscription required)

- ^ Stephen M. Stahl (15 May 2014). Prescriber’s guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 465–. ISBN 978-1-139-95300-9.

- ^ Grosshans M, Mutschler J, Kiefer F (2015). “Treatment of cocaine craving with as-needed nalmefene, a partial κ opioid receptor agonist: first clinical experience”. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 30 (4): 237–8. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000069. PMID 25647453.

- ^ Fulton, Brian S. (2014). Drug Discovery for the Treatment of Addiction: Medicinal Chemistry Strategies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 341. ISBN 9781118889572.

- ^ See: “Baxter discontinues Revex injection”. Monthly Prescribing Reference website. Haymarket Media, Inc. 9 July 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- ^ “Drug Shortages”. FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008.

- ^ “Efficacy of nalmefene in patients with alcohol dependence (ESENSE1)”.

- ^ “Lundbeck submits Selincro in EU; Novo Nordisk files Degludec in Japan”. The Pharma Letter. 22 December 2011.

- ^ “Selincro”. European Medicines Agency. 13 March 2013.

- ^ “Alcohol cravings drug nalmefene granted approval in Scotland”. BBC News. 7 October 2013.

- ^ “Nalmefene granted approval in England”. The Independent. 3 October 2014.

- ^ “Alcohol dependence treatment accepted for NHS use”. MIMS. 26 November 2014.

- ^ Bidlack, Jean M (2014). “Mixed κ/μ partial opioid agonists as potential treatments for cocaine dependence”. Adv. Pharmacol. 69: 387–418. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00010-X. PMID 24484983.

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Selincro |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605043 |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration |

By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 45% |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 10.8 ± 5.2 hours |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.948  |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H25NO3 |

| Molar mass | 339.43 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

Nalmefene

17-cyclopropylmethyl-4,5α-epoxy-6-methylenemorphinan-3,14-diol

march 1 2013

Lundbeck will be celebrating news that European regulators have issued a green light for Selincro, making it the first therapy approved for the reduction of alcohol consumption in dependent adults.

Selincro (nalmefene) is a unique dual-acting opioid system modulator that acts on the brain’s motivational system, which is dysregulated in patients with alcohol dependence.

The once daily pill has been developed to be taken on days when an alcoholic feels at greater risk of having a drink, in a strategy that aims to reduce – rather than stop – alcohol consumption, which some experts believe is a more realistic goal.

Clinical trials of the drug have shown that it can reduce alcohol consumption by approximately 60% after six months treatment, equating to an average reduction of nearly one bottle of wine per day.

In March last year, data was published from two Phase III trials, ESENSE 1 and ESENSE 2, showing that the mean number of heavy drinking days decreased from 19 to 7 days/month and 20 to 7 days/month, while TAC fell from 85 to 43g/day and from 93 to 30g/day at month six. However, the placebo effect was also strong in the studies.

According to Anders Gersel Pedersen, Executive Vice President and Head of Research & Development at Lundbeck, Selincro “represents the first major innovation in the treatment of alcohol dependence in many years,” and he added that its approval “is exciting news for the many patients with alcohol dependence who otherwise may not seek treatment”.

Alcohol dependence is considered a major public health concern, and yet it is both underdiagnosed and undertreated, highlighting the urgent need for better management of the condition.

In Europe, more than 90% of the 14 million patients with alcohol dependence are not receiving treatment, but research suggests that treating just 40% of these would save 11,700 lives each year.

The Danish firm said it expects to launch Selincro in its first markets in mid-2013, and that it will provide the drug as part of “a new treatment concept that includes continuous psychosocial support focused on the reduction of alcohol consumption and treatment adherence”.

Nalmefene (Revex), originally known as nalmetrene, is an opioid receptor antagonistdeveloped in the early 1970s, and used primarily in the management of alcoholdependence, and also has been investigated for the treatment of other addictions such aspathological gambling and addiction to shopping.

Nalmefene is an opiate derivative similar in both structure and activity to the opiate antagonist naltrexone. Advantages of nalmefene relative to naltrexone include longer half-life, greater oral bioavailability and no observed dose-dependent liver toxicity. As with other drugs of this type, nalmefene can precipitate acute withdrawal symptoms in patients who are dependent on opioid drugs, or more rarely when used post-operatively to counteract the effects of strong opioids used in surgery.

Nalmefene differs from naltrexone by substitution of the ketone group at the 6-position of naltrexone with a methylene group (CH2), which considerably increases binding affinity to the μ-opioid receptor. Nalmefene also has high affinity for the other opioid receptors, and is known as a “universal antagonist” for its ability to block all three.

- US patent 3814768, Jack Fishman et al, “6-METHYLENE-6-DESOXY DIHYDRO MORPHINE AND CODEINE DERIVATIVES AND PHARMACEUTICALLY ACCEPTABLE SALTS”, published 1971-11-26, issued 1974-06-04

- Barbara J. Mason, Fernando R. Salvato, Lauren D. Williams, Eva C. Ritvo, Robert B. Cutler (August 1999). “A Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Oral Nalmefene for Alcohol Dependence”. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56 (8): 719.

- Clinical Trial Of Nalmefene In The Treatment Of Pathological Gambling

- http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2000/20459S2lbl.pdf

- “Efficacy of Nalmefene in Patients With Alcohol Dependence (ESENSE1)”. “Lundbeck submits Selincro in EU; Novo Nordisk files Degludec in Japan”. thepharmaletter. 22 December 2011.

- Nalmefene Hydrochloride Drug Information, Professional

| NALMEFENE | |

|---|---|

| 17-cyclopropylmethyl-4,5α-epoxy-6-methylenemorphinan-3,14-diol |

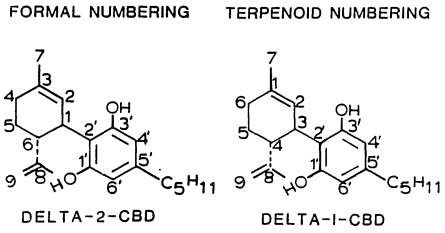

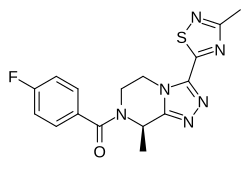

REVEX (nalmefene hydrochloride injection), an opioid antagonist, is a 6-methylene analogue of naltrexone. The chemical structure is shown below:

|

Molecular Formula: C21H25NO3•HCl

Molecular Weight: 375.9, CAS # 58895-64-0

Chemical Name: 17-(Cyclopropylmethyl)-4,5a-epoxy-6-methylenemorphinan-3,14-diol, hydrochloride salt.

Nalmefene hydrochloride is a white to off-white crystalline powder which is freely soluble in water up to 130 mg/mL and slightly soluble in chloroform up to 0.13 mg/mL, with a pKa of 7.6.

REVEX is available as a sterile solution for intravenous, intramuscular, and subcutaneous administration in two concentrations, containing 100 µg or 1.0 mg of nalmefene free base per mL. The 100 µg/mL concentration contains 110.8 µg of nalmefene hydrochloride and the 1.0 mg/mL concentration contains 1.108 mg of nalmefene hydrochloride per mL. Both concentrations contain 9.0 mg of sodium chloride per mL and the pH is adjusted to 3.9 with hydrochloric acid.

Concentrations and dosages of REVEX are expressed as the free base equivalent of nalmefene

////////////////////JF-1, NIH-10365, ORF-11676, SRD-174, JAPAN 2019, FDA 1995, Nalmefene hydrochloride dihydrate, ナルメフェン塩酸塩水和物 , Nalmefene, ema 2013, china, 2013, Lu-AA36143

DRUG APPROVALS BY DR ANTHONY MELVIN CRASTO …..

DRUG APPROVALS BY DR ANTHONY MELVIN CRASTO …..

amcrasto@gmail.com

amcrasto@gmail.com LIONEL MY SON

LIONEL MY SON

.png)

One mechanistic explanation proposed by Lee and coworkers (1).

One mechanistic explanation proposed by Lee and coworkers (1).