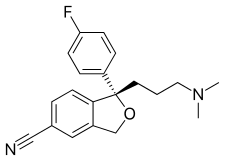

- Molecular FormulaC20H21FN2O

- Average mass324.392 Da

-

S-(+)-Citalopramэсциталопрам [Russian] [INN]إيسكيتالوبرام [Arabic] [INN]艾司西酞普兰 [Chinese] [INN]

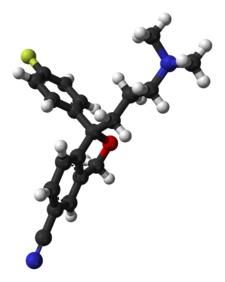

Lexapro® (escitalopram oxalate) is an orally administered selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Escitalopram is the pure Senantiomer (single isomer) of the racemic bicyclic phthalane derivative citalopram. Escitalopram oxalate is designated S-(+)-1-[3(dimethyl-amino)propyl]-1-(p-fluorophenyl)-5-phthalancarbonitrile oxalate with the following structural formula:

|

The molecular formula is C20H21FN2O • C2H2O4 and the molecular weight is 414.40.

Escitalopram oxalate occurs as a fine, white to slightly-yellow powder and is freely soluble in methanol and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), soluble in isotonic saline solution, sparingly soluble in water and ethanol, slightly soluble in ethyl acetate, and insoluble in heptane.

Lexapro (escitalopram oxalate) is available as tablets or as an oral solution.

Lexapro tablets are film-coated, round tablets containing escitalopram oxalate in strengths equivalent to 5 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg escitalopram base. The 10 and 20 mg tablets are scored. The tablets also contain the following inactive ingredients: talc, croscarmellose sodium, microcrystalline cellulose/colloidal silicon dioxide, and magnesium stearate. The film coating contains hypromellose, titanium dioxide, and polyethylene glycol.

Lexapro oral solution contains escitalopram oxalate equivalent to 1 mg/mL escitalopram base. It also contains the following inactive ingredients: sorbitol, purified water, citric acid, sodium citrate, malic acid, glycerin, propylene glycol, methylparaben, propylparaben, and natural peppermint flavor.

Escitalopram, also known by the brand names Lexapro and Cipralex among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adults and children over 12 years of age with major depressive disorder (MDD) or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Escitalopram is the (S)-stereoisomer(Left-enantiomer) of the earlier Lundbeck drug citalopram, hence the name escitalopram. Whether escitalopram exhibits superior therapeutic properties to citalopram or merely represents an example of “evergreening” is controversial.[2]

Medical uses

Escitalopram has FDA approval for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and adults, and generalized anxiety disorder in adults.[3] In European countries and Australia, it is approved for depression (MDD) and certain anxiety disorders: general anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.

Depression

Escitalopram was approved by regulatory authorities for the treatment of major depressive disorder on the basis of four placebo controlled, double-blind trials, three of which demonstrated a statistical superiority over placebo.[4]

Controversy exists regarding the effectiveness of escitalopram compared to its predecessor citalopram. The importance of this issue follows from the greater cost of escitalopram relative to the generic mixture of isomers citalopram prior to the expiration of the escitalopram patent in 2012, which led to charges of evergreening. Accordingly, this issue has been examined in at least 10 different systematic reviews and meta analyses. The most recent of these have concluded (with caveats in some cases) that escitalopram is modestly superior to citalopram in efficacy and tolerability.[5][6][7][8]

In contrast to these findings, a 2011 review concluded that all second-generation antidepressants are equally effective,[9] and treatment guidelines issued by the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence and by the American Psychiatric Association generally reflect this viewpoint.[10][11]

Anxiety disorder

Escitalopram appears to be effective in treating general anxiety disorder, with relapse on escitalopram (20%) less than placebo (50%).[12]

Other

Escitalopram as well as other SSRIs are effective in reducing the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome, whether taken in the luteal phase only or continuously.[13] There is no good data available for escitalopram for seasonal affective disorder as of 2011.[14] SSRIs do not appear to be useful for preventing tension headaches or migraines.[15][16]

Adverse effects

Escitalopram, like other SSRIs, has been shown to affect sexual functions causing side effects such as decreased libido, delayed ejaculation, genital anesthesia,[17] and anorgasmia.[18][19]

An analysis conducted by the FDA found a statistically insignificant 1.5 to 2.4-fold (depending on the statistical technique used) increase of suicidality among the adults treated with escitalopram for psychiatric indications.[20][21][22] The authors of a related study note the general problem with statistical approaches: due to the rarity of suicidal events in clinical trials, it is hard to draw firm conclusions with a sample smaller than two million patients.[23]

Escitalopram is not associated with significant weight gain. For example, 0.6 kg mean weight change after 6 months of treatment with escitalopram for depression was insignificant and similar to that with placebo (0.2 kg).[24] 1.4–1.8 kg mean weight gain was reported in 8-month trials of escitalopram for depression,[25] and generalized anxiety disorder.[26] A 52-week trial of escitalopram for the long-term treatment of depression in elderly also found insignificant 0.6 kg mean weight gain.[27] Escitalopram may help reduce weight in those treated for binge eating associated obesity.[28]

Citalopram and escitalopram are associated with dose-dependent QT interval prolongation[29] and should not be used in those with congenital long QT syndrome or known pre-existing QT interval prolongation, or in combination with other medicines that prolong the QT interval. ECG measurements should be considered for patients with cardiac disease, and electrolyte disturbances should be corrected before starting treatment. In December 2011, the UK implemented new restrictions on the maximum daily doses.[30][31] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada did not similarly order restrictions on escitalopram dosage, only on its predecessor citalopram.[32]

Escitalopram should be taken with caution when using Saint John’s wort.[33] Exposure to escitalopram is increased moderately, by about 50%, when it is taken with omeprazole. The authors of this study suggested that this increase is unlikely to be of clinical concern.[34] Caution should be used when taking cough medicine containing dextromethorphan (DXM) as serotonin syndrome, liver damage, and other negative side effects have been reported.

Discontinuation symptoms

Escitalopram discontinuation, particularly abruptly, may cause certain withdrawal symptoms such as “electric shock” sensations[35] (also known as “brain shivers” or “brain zaps”), dizziness, acute depressions and irritability, as well as heightened senses of akathisia.[36]

Pregnancy

There is a tentative association of SSRI use during pregnancy with heart problems in the baby.[37] Their use during pregnancy should thus be balanced against that of depression.[37]

Overdose

Excessive doses of escitalopram usually cause relatively minor untoward effects such as agitation and tachycardia. However, dyskinesia, hypertonia, and clonus may occur in some cases. Plasma escitalopram concentrations are usually in a range of 20–80 μg/L in therapeutic situations and may reach 80–200 μg/L in the elderly, patients with hepatic dysfunction, those who are poor CYP2C19 metabolizers or following acute overdose. Monitoring of the drug in plasma or serum is generally accomplished using chromatographic methods. Chiral techniques are available to distinguish escitalopram from its racemate, citalopram.[38][39][40] Escitalopram seems to be less dangerous than citalopram in overdose and comparable to other SSRIs.[41]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

| Receptor | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 2.5 |

| NET | 6,514 |

| 5-HT2C | 2,531 |

| α1 | 3,870 |

| M1 | 1,242 |

| H1 | 1,973 |

Escitalopram increases intrasynaptic levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin by blocking the reuptake of the neurotransmitter into the presynaptic neuron. Of the SSRIs currently on the market, escitalopram has the highest selectivity for the serotonin transporter (SERT) compared to the norepinephrine transporter (NET), making the side-effect profile relatively mild in comparison to less-selective SSRIs.[43] The opposite enantiomer, (R)-citalopram, counteracts to a certain degree the serotonin-enhancing action of escitalopram.[citation needed] As a result, escitalopram has been claimed to be a more potent antidepressant than the racemic mixture, citalopram, of the two enantiomers. In order to explain this phenomenon, researchers from Lundbeck proposed that escitalopram enhances its own binding via an additional interaction with another allosteric site on the transporter.[44] Further research by the same group showed that (R)-citalopram also enhances binding of escitalopram,[45] and therefore the allosteric interaction cannot explain the observed counteracting effect. In the most recent paper, however, the same authors again reversed their findings and reported that (R)-citalopram decreases binding of escitalopram to the transporter.[46] Although allosteric binding of escitalopram to the serotonin transporter is of unquestionable research interest, its clinical relevance is unclear since the binding of escitalopram to the allosteric site is at least 1000 times weaker than to the primary binding site.

Escitalopram is a substrate of P-glycoprotein and hence P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as verapamil and quinidine may improve its blood-brain penetrability.[47] In a preclinical study in rats combining escitalopram with a P-glycoprotein inhibitor enhanced its antidepressant-like effects.[47]

Interactions

Escitalopram, similarly to other SSRIs (with the exception of fluvoxamine), inhibits CYP2D6 and hence may increase plasma levels of a number of CYP2D6 substrates such as aripiprazole, risperidone, tramadol, codeine, etc. As much of the effect of codeine is attributable to its conversion (10%) to morphine its effectiveness will be reduced by this inhibition, not enhanced.[48] As escitalopram is only a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6, analgesia from tramadol may not be affected.[49] Escitalopram can also prolong the QT interval and hence it is not recommended in patients that are concurrently on other medications that have the ability to prolong the QT interval. Being a SSRI, escitalopram should not be given concurrently with MAOIs or other serotonergic medications.[43]

History

Escitalopram was developed in close cooperation between Lundbeck and Forest Laboratories. Its development was initiated in the summer of 1997, and the resulting new drug application was submitted to the U.S. FDA in March 2001. The short time (3.5 years) it took to develop escitalopram can be attributed to the previous extensive experience of Lundbeck and Forest with citalopram, which has similar pharmacology.[50] The FDA issued the approval of escitalopram for major depression in August 2002 and for generalized anxiety disorder in December 2003. On May 23, 2006, the FDA approved a generic version of escitalopram by Teva.[51] On July 14 of that year, however, the U.S. District Court of Delaware decided in favor of Lundbeck regarding the patent infringement dispute and ruled the patent on escitalopram valid.[52]

In 2006 Forest Laboratories was granted an 828-day (2 years and 3 months) extension on its US patent for escitalopram.[53] This pushed the patent expiration date from December 7, 2009 to September 14, 2011. Together with the 6-month pediatric exclusivity, the final expiration date was March 14, 2012.

Society and culture

Allegations of illegal marketing

In 2004, two separate civil suits alleging illegal marketing of citalopram and escitalopram for use by children and teenagers by Forest were initiated by two whistleblowers, one by a practicing physician named Joseph Piacentile, and the other by a Forest salesman named Christopher Gobble.[54] In February 2009, these two suits received support from the US Attorney for Massachusetts and were combined into one. Eleven states and the District of Columbia have also filed notices of intention to intervene as plaintiffs in the action. The suits allege that Forest illegally engaged in off-label promoting of Lexapro for use in children, that the company hid the results of a study showing lack of effectiveness in children, and that the company paid kickbacks to doctors to induce them to prescribe Lexapro to children. It was also alleged that the company conducted so-called “seeding studies” that were, in reality, marketing efforts to promote the drug’s use by doctors.[55][56] Forest responded to these allegations that it “is committed to adhering to the highest ethical and legal standards, and off-label promotion and improper payments to medical providers have consistently been against Forest policy.”[57] In 2010 Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., agreed to pay more than $313 million to settle the charges over Lexapro and two other drugs, Levothroid and Celexa.[58]

Brand names

Escitalopram is sold under many brand names worldwide such as Cipralex.[1]

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene.

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene.

A new method for the preparation of citalopram has been developed: The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (I) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (II), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (III) in THF yielding the corresponding amide (IV). The cyclization of (IV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (V), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (VI) in THF giving the benzophenone (VII). This compound (VII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (VIII) in the same solvent, providing the cabinol (IX), which is cyclized by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and Et3N in CH2Cl2 yielding the isobenzofuran (X). Finally, this compound is treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine to generate the 5-cyano substituent of citalopram.

A new method for the preparation of citalopram has been developed: The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (I) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (II), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (III) in THF yielding the corresponding amide (IV). The cyclization of (IV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (V), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (VI) in THF giving the benzophenone (VII). This compound (VII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (VIII) in the same solvent, providing the cabinol (IX), which is cyclized by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and Et3N in CH2Cl2 yielding the isobenzofuran (X). Finally, this compound is treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine to generate the 5-cyano substituent of citalopram.

The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (XII) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (XIII), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (XIV) in THF to yield the corresponding amide (XV). The cyclization of (XV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (XVI), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (XVII) in THF to give the benzophenone (XVIII). This compound (XVIII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (XIX) in the same solvent to provide the carbinol (XX), which is submitted to optical resolution with (+)- or (-)-tartaric acid, or (+)- or (-)-camphor-10-sulfonic acid (CSA) to give the desired (S)-enantiomer (XXI). Cyclization of (XXI) by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and TEA in dichloromethane yields the chiral isobenzofuran (XXII), which is finally treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine.

The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (XII) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (XIII), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (XIV) in THF to yield the corresponding amide (XV). The cyclization of (XV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (XVI), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (XVII) in THF to give the benzophenone (XVIII). This compound (XVIII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (XIX) in the same solvent to provide the carbinol (XX), which is submitted to optical resolution with (+)- or (-)-tartaric acid, or (+)- or (-)-camphor-10-sulfonic acid (CSA) to give the desired (S)-enantiomer (XXI). Cyclization of (XXI) by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and TEA in dichloromethane yields the chiral isobenzofuran (XXII), which is finally treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine.

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene.

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene.

Racemic 5-bromo-1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran (I) is submitted to optical resolution by chiral chromatography to give the corresponding (S)-isomer (II), which is treated with Zn(CN)2 and Pd(PPh3)4 to afford the target Escitalopram.

The esterification of racemic 1-[4-bromo-2-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl]-4-(dimethylamino)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-butanol (I) with (S)-2-(6-methoxynaphth-2-yl)propionyl chloride (II) by means of TEA and DMAP in THF gives the corresponding ester (III) as a diastereomeric mixture that is separated by chiral chromatography over Daicel AD, the desired diastereomer (IV) is easily isolated. Finally, this ester is hydrolyzed and simultaneously cyclized by means of NaH in DMF to provide the target intermediate (V). Other acyl chlorides such as (S)-2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propionyl chloride, (S)-O-acetylmandeloyl chloride, (S)-benzyloxycarbonylprolyl chloride, (S)-2-phenylbutyryl chloride, (S)-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride or (S)-N-acetylalanine can also be used in the preceding sequence.

The esterification of racemic 1-[4-bromo-2-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl]-4-(dimethylamino)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-butanol (I) with (S)-2-(6-methoxynaphth-2-yl)propionyl chloride (II) by means of TEA and DMAP in THF gives the corresponding ester (III) as a diastereomeric mixture that is separated by chiral chromatography over Daicel AD, the desired diastereomer (IV) is easily isolated. Finally, this ester is hydrolyzed and simultaneously cyclized by means of NaH in DMF to provide the target intermediate (V). Other acyl chlorides such as (S)-2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propionyl chloride, (S)-O-acetylmandeloyl chloride, (S)-benzyloxycarbonylprolyl chloride, (S)-2-phenylbutyryl chloride, (S)-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride or (S)-N-acetylalanine can also be used in the preceding sequence.

|

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b drugs.com Drugs.com international: Escitalopram Page accessed April 25, 2015

- Jump up^ NHS pays millions of pounds more than it needs to for drugs, The Independent. Retrieved 05/10/2011.

- Jump up^ “Escitalopram Oxalate”. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Jump up^ “www.accessdata.fda.gov” (PDF).

- Jump up^ Ramsberg J, Asseburg C, Henriksson M (2012). “Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antidepressants in primary care: a multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness model”. PLoS ONE. 7 (8): e42003. PMC 3410906

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 22876296. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042003.

. PMID 22876296. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042003. - Jump up^ Cipriani A, Purgato M, Furukawa TA, Trespidi C, Imperadore G, Signoretti A, Churchill R, Watanabe N, Barbui C (2012). “Citalopram versus other anti-depressive agents for depression”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7: CD006534. PMC 4204633

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 22786497. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006534.pub2.

. PMID 22786497. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006534.pub2. - Jump up^ Favré P (February 2012). “[Clinical efficacy and achievement of a complete remission in depression: increasing interest in treatment with escitalopram]”. Encephale (in French). 38(1): 86–96. PMID 22381728. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2011.11.003.

- Jump up^ Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Blanca-Tamayo M, Gimeno-de la Fuente V, Salvatella-Pasant J (December 2010). “Comparison of escitalopram vs. citalopram and venlafaxine in the treatment of major depression in Spain: clinical and economic consequences”. Curr Med Res Opin. 26 (12): 2757–64. PMID 21034375. doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.529430.

- Jump up^ Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, Thaler K, Lux L, Van Noord M, Mager U, Thieda P, Gaynes BN, Wilkins T, Strobelberger M, Lloyd S, Reichenpfader U, Lohr KN (Dec 6, 2011). “Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis.”. Annals of Internal Medicine. 155 (11): 772–85. PMID 22147715. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009.

- Jump up^ “CG90 Depression in adults: full guidance”.

- Jump up^ “PsychiatryOnline | APA Practice Guidelines | Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition”.[permanent dead link]

- Jump up^ Bech P, Lönn SL, Overø KF (2010). “Relapse prevention and residual symptoms: a closer analysis of placebo-controlled continuation studies with escitalopram in major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder”. J Clin Psychiatry. 71 (2): 121–9. PMID 19961809. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04749blu.

- Jump up^ Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O’Brien PM, Wyatt K (Jun 7, 2013). “Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome.”. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 6: CD001396. PMID 23744611. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub3.

- Jump up^ Thaler K, Delivuk M, Chapman A, Gaynes BN, Kaminski A, Gartlehner G (Dec 7, 2011). “Second-generation antidepressants for seasonal affective disorder.”. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (12): CD008591. PMID 22161433. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008591.pub2.

- Jump up^ Banzi, R; Cusi, C; Randazzo, C; Sterzi, R; Tedesco, D; Moja, L (1 May 2015). “Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for the prevention of tension-type headache in adults.”. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 5: CD011681. PMID 25931277. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011681.

- Jump up^ Moja, PL; Cusi, C; Sterzi, RR; Canepari, C (20 July 2005). “Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for preventing migraine and tension-type headaches.”. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (3): CD002919. PMID 16034880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002919.pub2.

- Jump up^ Bolton JM, Sareen J, Reiss JP (2006). “Genital anesthesia persisting six years after sertraline discontinuation”. J Sex Marital Ther. 32 (4): 327–30. PMID 16709553. doi:10.1080/00926230600666410.

- Jump up^ Clayton A, Keller A, McGarvey EL (2006). “Burden of phase-specific sexual dysfunction with SSRIs”. Journal of Affective Disorders. 91 (1): 27–32. PMID 16430968. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.007.

- Jump up^ “Lexapro prescribing information” (PDF).

- Jump up^ Levenson M, Holland C. “Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)”. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- Jump up^ Stone MB, Jones ML (2006-11-17). “Clinical Review: Relationship Between Antidepressant Drugs and Suicidality in Adults” (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Pharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- Jump up^ Levenson M; Holland C (2006-11-17). “Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants” (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Pharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- Jump up^ Khan A, Schwartz K (2007). “Suicide risk and symptom reduction in patients assigned to placebo in duloxetine and escitalopram clinical trials: analysis of the FDA summary basis of approval reports”. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 19 (1): 31–6. PMID 17453659. doi:10.1080/10401230601163550.

- Jump up^ Baldwin DS, Reines EH, Guiton C, Weiller E (2007). “Escitalopram therapy for major depression and anxiety disorders”. Ann Pharmacother. 41 (10): 1583–92. PMID 17848424. doi:10.1345/aph.1K089.

- Jump up^ Pigott TA, Prakash A, Arnold LM, Aaronson ST, Mallinckrodt CH, Wohlreich MM (2007). “Duloxetine versus escitalopram and placebo: an 8-month, double-blind trial in patients with major depressive disorder”. Curr Med Res Opin. 23 (6): 1303–18. PMID 17559729. doi:10.1185/030079907X188107.

- Jump up^ Davidson JR, Bose A, Wang Q (2005). “Safety and efficacy of escitalopram in the long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder”. J Clin Psychiatry. 66 (11): 1441–6. PMID 16420082. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n1115.

- Jump up^ Kasper S, Lemming OM, de Swart H (2006). “Escitalopram in the long-term treatment of major depressive disorder in elderly patients”. Neuropsychobiology. 54 (3): 152–9. PMID 17230032. doi:10.1159/000098650.

- Jump up^ Guerdjikova AI, McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Welge JA, Nelson E, Lake K, Alessio DD, Keck PE, Hudson JI (January 2008). “High-dose escitalopram in the treatment of binge-eating disorder with obesity: a placebo-controlled monotherapy trial”. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 23 (1): 1–11. PMID 18058852. doi:10.1002/hup.899.

- Jump up^ Castro VM, Clements CC, Murphy SN, Gainer VS, Fava M, Weilburg JB, Erb JL, Churchill SE, Kohane IS, Iosifescu DV, Smoller JW, Perlis RH (2013). “QT interval and antidepressant use: a cross sectional study of electronic health records”. BMJ. 346: f288. PMC 3558546

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 23360890. doi:10.1136/bmj.f288.

. PMID 23360890. doi:10.1136/bmj.f288. - Jump up^ “Citalopram and escitalopram: QT interval prolongation—new maximum daily dose restrictions (including in elderly patients), contraindications, and warnings”. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. December 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2013.

- Jump up^ van Gorp F, Whyte IM, Isbister GK (2009). “Clinical and ECG Effects of Escitalopram Overdose” (PDF). Annals of Emergency Medicine. 54 (3): 404–8. PMID 19556032. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.04.016.

- Jump up^ Hasnain M, Howland RH, Vieweg WV (2013). “Escitalopram and QTc prolongation”. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 38 (4): E11. PMC 3692726

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . doi:10.1503/jpn.130055.

. doi:10.1503/jpn.130055. - Jump up^ Karch, Amy (2006). 2006 Lippincott’s Nursing Drug Guide. Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, London, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 1-58255-436-6.

- Jump up^ Malling D, Poulsen MN, Søgaard B (2005). “The effect of cimetidine or omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of escitalopram in healthy subjects”. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 60 (3): 287–290. PMC 1884771

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 16120067. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02423.x.

. PMID 16120067. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02423.x. - Jump up^ Prakash O, Dhar V (2008). “Emergence of electric shock-like sensations on escitalopram discontinuation”. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 28 (3): 359–60. PMID 18480703. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181727534.

- Jump up^ “Lexapro (Escitalopram Oxalate) Drug Information: Warnings and Precautions – Prescribing Information at RxList”. Retrieved 2015-08-09.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gentile, S (1 July 2015). “Early pregnancy exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, risks of major structural malformations, and hypothesized teratogenic mechanisms.”. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 11: 1–13. PMID 26135630. doi:10.1517/17425255.2015.1063614.

- Jump up^ van Gorp F, Whyte IM, Isbister GK (2009). “Clinical and ECG effects of escitalopram overdose”. Ann Emerg Med. 54 (3): 404–8. PMID 19556032. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.04.016.

- Jump up^ Haupt D (1996). “Determination of citalopram enantiomers in human plasma by liquid chromatographic separation on a Chiral-AGP column”. J. Chromatogr. B, Biomed. Appl. 685(2): 299–305. PMID 8953171. doi:10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00177-6.

- Jump up^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man (8th ed.). Foster City, Ca: Biomedical Publications. pp. 552–553. ISBN 0962652377.

- Jump up^ White N, Litovitz T, Clancy C (December 2008). “Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type”. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 4 (4): 238–250. PMC 3550116

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 19031375. doi:10.1007/BF03161207.

. PMID 19031375. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. - Jump up^ Owens, MJ; Knight, DL; Nemeroff, CB (1 September 2001). “Second-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine.”. Biological Psychiatry. 50 (5): 345–50. PMID 11543737. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01145-3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional; 2010.

- Jump up^ For an overview of supporting data, see Sánchez C, Bøgesø KP, Ebert B, Reines EH, Braestrup C (2004). “Escitalopram versus citalopram: the surprising role of the R-enantiomer”. Psychopharmacology. 174 (2): 163–76. PMID 15160261. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1865-z.

- Jump up^ Chen F, Larsen MB, Sánchez C, Wiborg O (2005). “The (S)-enantiomer of (R,S)-citalopram, increases inhibitor binding to the human serotonin transporter by an allosteric mechanism. Comparison with other serotonin transporter inhibitors”. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (2): 193–198. PMID 15695064. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.08.008.

- Jump up^ Mansari ME, Wiborg O, Mnie-Filali O, Benturquia N, Sánchez C, Haddjeri N (2007). “Allosteric modulation of the effect of escitalopram, paroxetine and fluoxetine: in-vitro and in-vivo studies”. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 10 (1): 31–40. PMID 16448580. doi:10.1017/S1461145705006462.

- ^ Jump up to:a b O’Brien FE, O’Connor RM, Clarke G, Dinan TG, Griffin BT, Cryan JF (October 2013). “P-glycoprotein inhibition increases the brain distribution and antidepressant-like activity of escitalopram in rodents”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (11): 2209–2219. PMC 3773671

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 23670590. doi:10.1038/npp.2013.120.

. PMID 23670590. doi:10.1038/npp.2013.120. - Jump up^ Ali Torkamani. “Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and CYP2D6”. Medscape.com. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Jump up^ Noehr-Jensen, L; Zwisler, ST; Larsen, F; Sindrup, SH; Damkier, P; Brosen, K (December 2009). “Escitalopram is a weak inhibitor of the CYP2D6-catalyzed O-demethylation of (+)-tramadol but does not reduce the hypoalgesic effect in experimental pain.”. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 86 (6): 626–33. PMID 19710642. doi:10.1038/clpt.2009.154.

- Jump up^ “2000 Annual Report. p 28 and 33” (PDF). Lundbeck. 2000. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- Jump up^ Miranda Hitti. “FDA OKs Generic Depression Drug – Generic Version of Lexapro Gets Green Light”. WebMD. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Jump up^ Marie-Eve Laforte (2006-07-14). “US court upholds Lexapro patent”. FirstWord. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Jump up^ “Forest Laboratories Receives Patent Term Extension for Lexapro” (Press release). PRNewswire-FirstCall. 2006-03-02. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- Jump up^ “Forest Laboratories: A Tale of Two Whistleblowers” article by Alison Frankel in The American Lawyer February 27, 2009

- Jump up^ United States of America v. Forest Laboratories Full text of the federal complaint filed in the US District Court for the district of Massachusetts

- Jump up^ “Drug Maker Is Accused of Fraud” article by Barry Meier and Benedict Carey in The New York Times February 25, 2009

- Jump up^ “Forest Laboratories, Inc. Provides Statement in Response to Complaint Filed by U.S. Government” Forest press-release. February 26, 2009.

- Jump up^ “Drug Maker Forest Pleads Guilty; To Pay More Than $313 Million to Resolve Criminal Charges and False Claims Act Allegations”. http://www.justice.gov.

Cited texts

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (September 2009). British National Formulary (BNF 58). UK: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85369-778-7.

Further reading

- “A Drug Maker’s Playbook Reveals a Marketing Strategy” article in The New York Times by Gardiner Harris, September 1, 2009

External links

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal — Escitalopram

- Lexapro (Forest Laboratories) Official Lexapro homepage

- Cipralex (Lundbeck) Official Cipralex homepage

- Pharmacological information Lexapro

- Cipla Medpro Official Cipla Medpro homepage

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |  pronunciation (help·info) pronunciation (help·info) |

| Trade names | Cipralex, Lexapro and many others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603005 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% |

| Protein binding | ~56% |

| Metabolism | Liver, specifically the enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 |

| Biological half-life | 27–32 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H21FN2O |

| Molar mass | 324.392 g/mol (414.43 as oxalate) |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

///////////////////S-(+)-Citalopram, эсциталопрам , إيسكيتالوبرام , 艾司西酞普兰 , CITALOPRAM

http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/101297/15/15_chapter%206.pdf

Filed under: Uncategorized Tagged: ESCITALOPRAM, 艾司西酞普兰, эсциталопрам, S-(+)-Citalopram, إيسكيتالوبرام