Abacavir (ABC) is a medication used to prevent and treat HIV/AIDS.[1][2] Similar to other nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), abacavir is used together with other HIV medications, and is not recommended by itself.[3] It is taken by mouth as a tablet or solution and may be used in children over the age of three months.[1][4]

Abacavir is generally well tolerated.[4] Common side effects include vomiting, trouble sleeping, fever, and feeling tired.[1] More severe side effects include hypersensitivity, liver damage, and lactic acidosis.[1] Genetic testing can indicate whether a person is at higher risk of developing hypersensitivity.[1] Symptoms of hypersensitivity include rash, vomiting, and shortness of breath.[4] Abacavir is in the NRTI class of medications, which work by blocking reverse transcriptase, an enzyme needed for HIV virus replication.[5] Within the NRTI class, abacavir is a carbocyclic nucleoside.[1]

Abacavir was patented in 1988 and approved for use in the United States in 1998.[6][7] It is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[8] It is available as a generic medication.[1] The wholesale cost in the developing world as of 2014 is between US$0.36 and US$0.83 per day.[9] As of 2016 the wholesale cost for a typical month of medication in the United States is US$70.50.[10] Commonly, abacavir is sold together with other HIV medications, such as abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine, abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine, and abacavir/lamivudine.[4][5]

Medical uses

Abacavir tablets and oral solution, in combination with other antiretroviral agents, are indicated for the treatment of HIV-1 infection.

Abacavir should always be used in combination with other antiretroviral agents. Abacavir should not be added as a single agent when antiretroviral regimens are changed due to loss of virologic response.

Side effects

Common adverse reactions include nausea, headache, fatigue, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite and trouble sleeping. Rare but serious side effects include hypersensitivity reaction or rash, elevated AST and ALT, depression, anxiety, fever/chills, URI, lactic acidosis, hypertriglyceridemia, and lipodystrophy.[11]

People with liver disease should be cautious about using abacavir because it can aggravate the condition. Signs of liver problems include nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, dark-colored urine and yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes. The use of nucleosidedrugs such as abacavir can very rarely cause lactic acidosis. Signs of lactic acidosis include fast or irregular heartbeat, unusual muscle pain, fatigue, difficulty breathing and stomach pain with nausea and vomiting.[12] Abacavir can also lead to immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, a change in body fat as well as an increased risk of heart attack.

Resistance to abacavir has developed in laboratory versions of HIV which are also resistant to other HIV-specific antiretrovirals such as lamivudine, didanosine, and zalcitabine. HIV strains that are resistant to protease inhibitors are not likely to be resistant to abacavir.

Abacavir is contraindicated for use in infants under 3 months of age.

Little is known about the effects of Abacavir overdose. Overdose victims should be taken to a hospital emergency room for treatment.

Hypersensitivity syndrome

Hypersensitivity to abacavir is strongly associated with a specific allele at the human leukocyte antigen B locus namely HLA-B*5701.[13][14][15] There is an association between the prevalence of HLA-B*5701 and ancestry. The prevalence of the allele is estimated to be 3.4 to 5.8 percent on average in populations of European ancestry, 17.6 percent in Indian Americans, 3.0 percent in Hispanic Americans, and 1.2 percent in Chinese Americans.[16][17] There is significant variability in the prevalence of HLA-B*5701 among African populations. In African Americans, the prevalence is estimated to be 1.0 percent on average, 0 percent in the Yorubafrom Nigeria, 3.3 percent in the Luhya from Kenya, and 13.6 percent in the Masai from Kenya, although the average values are derived from highly variable frequencies within sample groups.[18]

Common symptoms of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome include fever, malaise, nausea, and diarrhea. Some patients may also develop a skin rash.[19] Symptoms of AHS typically manifest within six weeks of treatment using abacavir, although they may be confused with symptoms of HIV, immune reconstitution syndrome, hypersensitivity syndromes associated with other drugs, or infection.[20] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released an alert concerning abacavir and abacavir-containing medications on July 24, 2008,[21] and the FDA-approved drug label for abacavir recommends pre-therapy screening for the HLA-B*5701 allele and the use of alternative therapy in subjects with this allele.[22] Additionally, both the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group recommend use of an alternative therapy in individuals with the HLA-B*5701 allele.[23][24]

Skin-patch testing may also be used to determine whether an individual will experience a hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir, although some patients susceptible to developing AHS may not react to the patch test.[25]

The development of suspected hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir requires immediate and permanent discontinuation of abacavir therapy in all patients, including patients who do not possess the HLA-B*5701 allele. On March 1, 2011, the FDA informed the public about an ongoing safety review of abacavir and a possible increased risk of heart attack associated with the drug. A meta-analysis of 26 studies conducted by the FDA, however, did not find any association between abacavir use and heart attack [26][27]

Immunopathogenesis

The mechanism underlying abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome is related to the change in the HLA-B*5701 protein product. Abacavir binds with high specificity to the HLA-B*5701 protein, changing the shape and chemistry of the antigen-binding cleft. This results in a change in immunological tolerance and the subsequent activation of abacavir-specific cytotoxic T cells, which produce a systemic reaction known as abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome.[28]

Interaction

Abacavir, and in general NRTIs, do not undergo hepatic metabolism and therefore have very limited (to none) interaction with the CYP enzymes and drugs that effect these enzymes. That being said there are still few interactions that can affect the absorption or the availability of abacavir. Below are few of the common established drug and food interaction that can take place during abacavir co-administration:

- Protease inhibitors such as tipranavir or ritonovir may decrease the serum concentration of abacavir through induction of glucuronidation. Abacavir is metabolized by both alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronidation.[29][30]

- Ethanol may result in increased levels of abacavir through the inhibition of alcohol dehydrogenase. Abacavir is metabolized by both alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronidation.[29][31]

- Methadone may diminish the therapeutic effect of Abacavir. Abacavir may decrease the serum concentration of Methadone.[32][33]

- Orlistat may decrease the serum concentration of antiretroviral drugs. The mechanism of this interaction is not fully established but it is suspected that it is due to the decreased absorption of abacavir by orlistat.[34]

- Cabozantinib: Drugs from the MPR2 inhibitor (Multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 inhibitors) family such as abacavir could increase the serum concentration of Cabozantinib.[35]

Mechanism of action

Abacavir is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor that inhibits viral replication. It is a guanosine analogue that is phosphorylated to carbovir triphosphate (CBV-TP). CBV-TP competes with the viral molecules and is incorporated into the viral DNA. Once CBV-TP is integrated into the viral DNA, transcription and HIV reverse transcriptase is inhibited.[36]

Pharmacokinetics

Abacavir is given orally and is rapidly absorbed with a high bioavailability of 83%. Solution and tablet have comparable concentrations and bioavailability. Abacavir can be taken with or without food.

Abacavir can cross the blood-brain barrier. Abacavir is metabolized primarily through the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronyl transferase to an inactive carboxylate and glucuronide metabolites. It has a half-life of approximately 1.5-2.0 hours. If a person has liver failure, abacavir’s half life is increased by 58%.

Abacavir is eliminated via excretion in the urine (83%) and feces (16%). It is unclear whether abacavir can be removed by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.[36]

History

Robert Vince and Susan Daluge along with Mei Hua, a visiting scientist from China, developed the medication in the ’80s.[37][38][39]

Abacavir was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 18, 1998, and is thus the fifteenth approved antiretroviral drug in the United States. Its patent expired in the United States on 2009-12-26.

Synthesis

Abacavir synthesis:[40]

References

ABOVE From internet free resources

- Crimmins, M. T.; King, B. W. (1996). “An Efficient Asymmetric Approach to Carbocyclic Nucleosides: Asymmetric Synthesis of 1592U89, a Potent Inhibitor of HIV Reverse Transcriptase”. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 61 (13): 4192–4193. doi:10.1021/jo960708p. PMID 11667311.

| AU 8937025; EP 0349242; JP 1990045486; JP 1999139976; US 5034394; US 5089500

|

SYN 2

The condensation of (?-cis-4-acetamido-2-cyclopentenylmethyl acetate (XIV) with 2-amino-4,6-dichloropyrimidine (XV) by means of Ba(OH)2 and triethylamine in refluxing butanol gives the expected condensation product (XVI), which is treated with 4-chlorophenyldiazonium chloride (XVII) in water/acetic acid to yield the corresponding azo-compound (XVIII). The reduction of (XVIII) with Zn/acetic acid in ethanol affords the diamine (XIX), which is cyclized with refluxing diethoxymethyl acetate (XX) to afford the corresponding purine (XXI). The reaction of (XXI) with cyclopropylamine (X) in refluxing ethanol affords racemic abacavir (XXII), which is phosphorylated with POCl3 giving the racemic 4′-O-phosphate (XXIII). Finally, this compound is submitted to stereoselective enzymatic dephosphorylation using snake venom 5′-nucleotidase (EC 3.1.3.5) from Crotalus atrox yielding the (-)-enantiomer, abacavir.

SYN 3

The acylation of 4(S)-benzyloxazolidin-2-one (XXIV) with 4-pentenoyl pivaloyl anhydride (XXV) by means of NaH in THF gives 4(S)-benzyl-3-(4-pentenoyl)oxazolidin-2-one (XXVI), which is submitted to a diastereoselective syn aldol condensation with acrolein (XXVII), using dibutylboron triflate as catalyst, affording the aldol (XXVIII). The cyclization of (XXVIII) by means of the Grubbs catalyst in dichloromethane yields the cyclopentenol (XXIX), which is reduced with LiBH4 in THF/methanol to give the key intermediate 5(R)-(hydroxymethyl)-2-cyclopenten-1(R)-ol (XXX). The reaction of (XXX) with methyl chloroformate/pyridine/DMAP or methyl chloroformate/triethylamine/DMAP or acetic anhydride gives the diols (XXXI), (XXXII) and (XXXIII), respectively, each of which coupled with 2-amino-6-chloropurine (XXXIV) in the presence of NaH and palladium tetrakis(triphenylphosphine) in THF/DMSO, affords the purine intermediate (IX) already reported.

SYN

The water promoted condensation of glyoxylic acid (XXXV) with cyclopentadiene (XXXVI) gives the racemic cis-hydroxylactone (XXXVII), which is acetylated with acetic anhydride to the acetate (XXXVIII). The selective enzymatic hydrolysis of (XXXVIII) with Pseudomonas fluorescens lipase yields the pre (-)-enantiomer (XXXIX), which is reduced with LiAlH4 in refluxing THF, affording triol (XL). The oxidation of the vicinal glycol of (XL) with NaIO4 in ethyl ether/water yields the hydroxyaldehyde (XLI), which is reduced with NaBH4 in ethanol to give the key intermediate 5(R)-(hydroxymethyl)-2-cyclopenten-1(R)-ol (XXX). This compound, by reaction with triphosgene and triethylamine in dichloromethane, results in the cyclic carbonate intermediate (XXXII), already reported.

SYN

A new solid phase synthesis of abacavir has been reported: Condensation of the chiral 4(R)-benzyl-3-(4-pentenoyl)oxazolidin-2-thione (I) with acrolein (II) by means of TiCl4 and DIEA gives the adduct (III), which was transformed into the chiral cyclopentene (IV) by catalytic ring-closing metathesis. The reductive removal of the chiral auxiliary with LiBH4 affords the chiral diol (V), which is selectively silylated with TBDMSCl providing the primary silyl ether (VI). Acylation of the secondary alcohol of (VI) with benzoic anhydride gives the benzoate (VII), which is desilylated with HF in acetonitrile yielding the allylic benzoate (VIII). Benzoate (VIII) is condensed with a p-nitrophenyl Wang carbonate resin (IX) by means of DIEA and DMAP affording the solid phase resin (X) which is condensed with 2-amino-6-chloropurine (XI) by means of a Pd catalyst furnishing the adduct (XII). Thermal condensation of (XII) with cyclopropylamine (XIII) yields the diaminopurine resin (XIV) which, after cleavage from the resin by a treatment with TFA in dichloromethane, gives directly abacavir.

SYN

The condensation of the chiral oxazolidinone (I) with the pentenoic anhydride (II) by means of n-BuLi in THF gives the N-pentenoyloxazolidinone (III), which is condensed with acrolein (IV) catalyzed by TiCl4 and (-)-spartein in dichloromethane, yielding the chiral adduct (V). The ring-closing metathesis of (V) by means of a Ru catalyst in dichloromethane affords the chiral cyclopentenol derivative (VI), which is reduced to the (R,R)-5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-cyclopenten-1-ol (VII) by means of LiBH4 in THF. The reaction of diol (VII) with Ac2O; with methyl chloroformate, TEA and DMAP; or with ethyl chloroformate and pyridine gives the diacetate (VIII), the cyclic carbonate (IX) or the dicarbonate (X), respectively. The condensation of (VIII), (IX) or (X) with 2-amino-6-chloropurine (XI) by means of Pd(PPh3)4 yields the carbocyclic purines (XII), (XIII) or (XIV), respectively. Finally, these compounds are hydrolyzed with aqueous NaOH to the target carbocyclic guanine.

The condensation of the chiral oxazolidinone (I) with the pentenoic anhydride (II) by means of n-BuLi in THF gives the N-pentenoyloxazolidinone (III), which is condensed with acrolein (IV) catalyzed by TiCl4 and (-)-spartein in dichloromethane, yielding the chiral adduct (V). The ring-closing metathesis of (V) by means of a Ru catalyst in dichloromethane affords the chiral cyclopentenol derivative (VI), which is reduced to the (R,R)-5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-cyclopenten-1-ol (VII) by means of LiBH4 in THF. The reaction of diol (VII) with Ac2O; with methyl chloroformate, TEA and DMAP; or with ethyl chloroformate and pyridine gives the diacetate (VIII), the cyclic carbonate (IX) or the dicarbonate (X), respectively. The condensation of (VIII), (IX) or (X) with 2-amino-6-chloropurine (XI) by means of Pd(PPh3)4 yields the carbocyclic purines (XII), (XIII) or (XIV), respectively. Finally, these compounds are hydrolyzed with aqueous NaOH to the target carbocyclic guanine.

SYN

Alternatively, the (R,R)-5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-cyclopenten-1-ol (VII) can also be obtained as follows: The condensation of the chiral oxazolidinethione (XV) with the pentenoic anhydride (II) by means of n-BuLi in THF gives the N-pentenoyloxazolidinethione (XVI), which is condensed with crotonaldehyde (XVII) catalyzed by TiCl4 and (-)-spartein in dichloromethane, yielding the chiral adduct (XVIII). The ring-closing metathesis of (XVIII) by means of a Ru catalyst in dichloromethane affords the chiral cyclopentenol derivative (XIX), which is reduced to the target diol (VII) by means of LiBH4 in THF.

SYN

An efficient asymmetric synthesis of abacavir has been reported: Acylation of the chiral oxazolidinone (I) with the mixed anhydride (II) by means of BuLi in THF gives the N-pentenoyloxazolidinone (III), which by condensation with acrolein (IV) catalyzed by TiCl4 and (?-spartein in dichloromethane yields the chiral adduct (V). The ring-closing metathesis of adduct (V) by means of the ruthenium catalyst (Cy3P)Cl2Ru=CHPh in dichloromethane affords the chiral cyclopentenol (VI), which is reduced to 5(R)-(hydroxymethyl)-2-cyclopenten-1(R)-ol (VII) by means of LiBH4 in THF. Reaction of diol (VII) with a) Ac2O, TEA and DMAP, b) methyl chloroformate, TEA and DMAP or c) methyl chloroformate, pyridine and DMAP gives a) the diacetate (VIII), b) the cyclic carbonate (IX) or c) the dicarbonate (X), respectively. The condensation of diacetate (VIII), cyclic carbonate (IX) or dicarbonate (X) with 2-amino-6-chloropurine (XI) by means of Pd(PPh3)4 yields the carbocyclic purines (XII), (XIII) or (XIV), respectively. Treatment of these chloro-purines (XII), (XIII) and (XIV) with cyclopropylamine (XV) in hot DMSO provides the corresponding cyclopropylaminopurine carbonate (XVI), abacavir or cyclopropylaminopurine acetate (XVII), respectively. Finally, the protecting groups of purines (XVI) and (XVII) are hydrolyzed with aqueous NaOH.

SYN

Alternatively, 5(R)-(hydroxymethyl)-2-cyclopenten-1(R)-ol (VII) can also be obtained as follows: Acylation of the chiral oxazolidinethione (XIX) with the mixed anhydride (II) by means of BuLi in THF gives the N-pentenoyl-oxazolidinethione (XX), which by condensation with crotonaldehyde (XXI) catalyzed by TiCl4 and (?-spartein in dichloromethane yields the chiral adduct (XXII). The ring-closing metathesis of (XXII) by means of the ruthenium catalyst in dichloromethane affords the chiral cyclopentenol derivative (XXIII), which is reduced to the target diol (VII) by means of LiBH4 in THF.

SYN

Alternatively, 2-amino-6-chloropurine (XI) is treated with cyclopropylamine (XV) in hot DMSO to give 2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)purine (XVIII), which is condensed with the chiral diacetate (VIII) by means of Pd(PPh3)4 to yield the carbocyclic purine acetate (XVI). Finally, purine (XVI) is deprotected by hydrolysis with aqueous NaOH.

CLIP

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960894X15007581

CLIP

CLIP

CLIP

Production of Abacavir

030-8 1.0g (0.0053mol), in the reaction flask was added cesium carbonate 1.75 g (0.0054 mol) and dry DMSO 50ml, stirred under N2 protection, the temperature was raised to 60 °C and stirred at this temperature for 2 h the mixture wascooled to room temperature, then add tetrakis (triphenylphosphine) combined palladium (TTP) [0.85 (0.00074mol)] and compound 030-5 [0.79g (0.0034 mol), DMSO (10 ml) solution was stirred and heated to 65 °C held 65 °C and stirred reaction 2.25h. The you can get the mixture containing compounds 030-9.

To the mixture was added methanol 100ml and K2CO3 is 2.10g, the mixture reaction was stirred for 45min at 40 °C, a solid precipitate which was filtered through a Celite layer and the filtrate was evaporated to a small volume under vacuum at 90 °C, and the remaining gum pounding mill was extracted with dichloromethane (100ml * 2) to give a brown solid residue was purified by silica gel (Merck 9385) column chromatography [eluent: dichloromethane / methanol (volume ratio 9:1)] to give a yellow foam was 030 0.26 g, yield 26.8.

CLIP

https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2012/ra/c2ra20842c

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h “Abacavir Sulfate”. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ “Drug Name Abbreviations Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines”. AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-08.

- ^ “What Not to Use Adult and Adolescent ARV Guidelines”. AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-08.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Yuen, GJ; Weller, S; Pakes, GE (2008). “A review of the pharmacokinetics of abacavir”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 47 (6): 351–71. doi:10.2165/00003088-200847060-00001. PMID 18479171.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs or ‘nukes’) – HIV/AIDS”. http://www.hiv.va.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-08.

- ^ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 505. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ Kane, Brigid M. (2008). HIV/AIDS Treatment Drugs. Infobase Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 9781438102078. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ “WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)” (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ “International Drug Price Indicator Guide”. ERC. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ “NADAC as of 2016-12-07 | Data.Medicaid.gov”. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ “Abacavir Adverse Reactions”. Epocrates Online.

- ^ “Abacavir | Dosage, Side Effects | AIDSinfo”. AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2016-11-08.

- ^ Mallal, S., Phillips, E., Carosi, G.; et al. (2008). “HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir”. New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (6): 568–579. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0706135. PMID 18256392.

- ^ Rauch, A., Nolan, D., Martin, A.; et al. (2006). “Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study”. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (1): 99–102. doi:10.1086/504874. PMID 16758424.

- ^ Dean, Laura (2012), Pratt, Victoria; McLeod, Howard; Rubinstein, Wendy; Dean, Laura (eds.), “Abacavir Therapy and HLA-B*57:01 Genotype”, Medical Genetics Summaries, National Center for Biotechnology Information (US), PMID 28520363, retrieved 2019-01-14

- ^ Heatherington; et al. (2002). “Genetic variations in HLA-B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir”. Lancet. 359 (9312): 1121–1122. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08158-8. PMID 11943262.

- ^ Mallal; et al. (2002). “Association between presence of HLA*B5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir”. Lancet. 359(9308): 727–732. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x. PMID 11888582.

- ^ Rotimi, C. N.; Jorde, L. B. (2010). “Ancestry and disease in the age of genomic medicine”. New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (16): 1551–1558. doi:10.1056/nejmra0911564. PMID 20942671.

- ^ Phillips, E., Mallal, S. (2009). “Successful translation of pharmacogenetics into the clinic”. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 13: 1–9. doi:10.1007/bf03256308.

- ^ Phillips, E., Mallal S. (2007). “Drug hypersensitivity in HIV”. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 7 (4): 324–330. doi:10.1097/aci.0b013e32825ea68a. PMID 17620824.

- ^ “Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers – Information for Healthcare Professionals: Abacavir (marketed as Ziagen) and Abacavir-Containing Medications”. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the US FDA. Archived from the original on 2013-12-11. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-07-31.

- ^ Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, de Boer A, et al. (May 2011). “Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte–an update of guidelines”. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 89 (5): 662–73. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.34. PMID 21412232.

- ^ Martin MA, Hoffman JM, Freimuth RR, et al. (May 2014). “Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for HLA-B Genotype and Abacavir Dosing: 2014 update”. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 95 (5): 499–500. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.38. PMC 3994233. PMID 24561393.

- ^ Shear, N.H., Milpied, B., Bruynzeel, D. P.; et al. (2008). “A review of drug patch testing and implications for HIV clinicians”. AIDS. 22 (9): 999–1007. doi:10.1097/qad.0b013e3282f7cb60. PMID 18520343.

- ^ “FDA Alert: Abacavir – Ongoing Safety Review: Possible Increased Risk of Heart Attack”. Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2013-12-10. Retrieved 2013-11-29.

- ^ Ding X, Andraca-Carrera E, Cooper C, et al. (December 2012). “No association of abacavir use with myocardial infarction: findings of an FDA meta-analysis”. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 61 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826f993c. PMID 22932321.

- ^ Illing, PT; et al. (2012). “Immune self-reactivity triggered by drug-modified HLA-peptide repertoire”. Nature. 486 (7404): 554–8. doi:10.1038/nature11147. PMID 22722860.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Prescribing information. Ziagen (abacavir). Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline, July 2002

- ^ Vourvahis, M; Kashuba, AD (2007). “Mechanisms of Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Drug Interactions Associated with Ritonavir-Enhanced Tipranavir”. Pharmacotherapy. 27 (6): 888–909. doi:10.1592/phco.27.6.888. PMID 17542771.

- ^ McDowell, JA; Chittick, GE; Stevens, CP; et al. (2000). ““, “Pharmacokinetic Interaction of Abacavir (1592U89) and Ethanol in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Adults”. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 44 (6): 1686–90. doi:10.1128/aac.44.6.1686-1690.2000. PMC 89933. PMID 10817729.

- ^ Berenguer, J; Perez-Elias, MJ; Bellon, JM; et al. (2006). “Effectiveness and safety of abacavir, lamivudine, and zidovudine in antiretroviral therapy-naive HIV-infected patients: results from a large multicenter observational cohort”. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 41 (2): 154–159. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000194231.08207.8a. PMID 16394846.

- ^ Dolophine(methadone) [prescribing information]. Columbus, OH: Roxane Laboratories, Inc.; March 2015.

- ^ Gervasoni, C; Cattaneo, D; Di Cristo, V; et al. (2016). “Orlistat: weight lost at cost of HIV rebound”. J Antimicrob Chemother. 71 (6): 1739–1741. doi:10.1093/jac/dkw033. PMID 26945709.

- ^ Cometriq (cabozantinib) [prescribing information]. South San Francisco, CA: Exelixis, Inc.; May 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Product Information: ZIAGEN(R) oral tablets, oral solution, abacavir sulfate oral tablets, oral solution. ViiV Healthcare (per Manufacturer), Research Triangle Park, NC, 2015.

- ^ “Dr. Robert Vince – 2010 Inductee”. Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame. Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ “Robert Vince, PhD (faculty listing)”. University of Minnesota. University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 2016-02-17.

- ^ Daluge SM, Good SS, Faletto MB, Miller WH, St Clair MH, Boone LR, Tisdale M, Parry NR, Reardon JE, Dornsife RE, Averett DR (May 1997). “1592U89, a novel carbocyclic nucleoside analog with potent, selective anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity”. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 41 (5): 1082–1093. doi:10.1128/AAC.41.5.1082. PMC 163855. PMID 9145874.

- ^ Crimmins, M. T.; King, B. W. (1996). “An Efficient Asymmetric Approach to Carbocyclic Nucleosides: Asymmetric Synthesis of 1592U89, a Potent Inhibitor of HIV Reverse Transcriptase”. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 61 (13): 4192–4193. doi:10.1021/jo960708p. PMID 11667311.

External links

- Full Prescribing Information

- Abacavir pathway on PharmGKB

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG)

References

-

- Crimmins, M.T. et al.: J. Org. Chem. (JOCEAH) 61 4192 (1996).

- b Olivo, H.F. et al.: J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 (JCPRB4) 1998, 391.

- US 5 089 500 (Burroughs Wellcome; 18.2.1992; GB-prior. 27.6.1988).

- a EP 434 450 (Wellcome Found.; 26.6.1991; appl. 21.12.1990; USA-prior. 22.12.1989).

- EP 1 857 458 (Solmag; appl. 5.5.2006).

- aa EP 424 064 (Enzymatix; appl. 24.4.1991; GB-prior. 16.10.1989).

- US 6 340 587 (SmithKline Beecham; 22.1.2002; appl. 20.8.1998; GB-prior. 22.8.1997).

- c US 5 034 394 (Welcome Found.; 23.7.1991; appl. 22.12.1989; GB-prior. 27.6.1988).

- d WO 9 924 431 (Glaxo; appl. 12.11.1998; WO-prior. 12.11.1997).

-

Alternative syntheses:

- EP 878 548 (Lonza; appl. 13.5.1998; CH-prior. 13.5.1997).

-

Preparation of chloropyrimidine intermediate V:

- US 6 448 403 (SmithKline Beecham; 10.9.2002; appl. 3.2.1995; GB-prior. 4.2.1994).

-

Condensation of pyrimidines with cyclopentylamine IV:

- Vince, R.; Hua, M.: J. Med. Chem. (JMCMAR) 33 (1), 17 (1990).

- Grumam, A. et al.: Tetrahedron Lett. (TELEAY) 36 (42), 7767 (1995).

- EP 349 242 (Wellcome Found.; appl. 26.6.1989; GB-prior. 27.6.1988).

- EP 366 385 (Wellcome Found.; appl. 23.10.1989; GB-prior. 24.10.1988).

- US 6 646 125 (SmithKline Beecham; 11.11.2003; appl. 14.10.1998; GB-prior. 14.10.1997).

- JP 1 022 853 (Asahi Glass Co.; appl. 17.7.1987).

-

Alternative preparation of 4-amino-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol:

- EP 926 131 (Lonza; appl. 24.11.1998; CH-prior. 27.11.1997).

- WO 9 745 529 (Lonza; appl. 30.5.1997; CH-prior. 30.5.1996).

- WO 9 910 519 (Glaxo; 4.3.1999; GB-prior. 20.8.1998).

- WO 9 824 741 (Glaxo; 11.6.1998; GB-prior. 7.12.1996).

- WO 2 001 017 952 (Chirotech; 15.3.2001; GB-prior. 9.9.1999).

-

Abacavir hemisulfate salt:

- US 6 294 540 (Glaxo Wellcome; 25.9.2001; appl. 14.5.1998; GB-prior. 17.5.1997).

-

Abacavir succinate as antiviral agent:

- WO 9 606 844 (Wellcome; 7.3.1996; appl. 25.8.1995; GB-prior. 26.8.1994).

-

Pharmaceutical formulations:

- US 6 641 843 (SmithKline Beecham; 4.11.2003; appl. 4.2.1999; GB-prior. 6.2.1998).

-

Synergistic combinations for treatment of HIV infection:

- WO 9 630 025 (Wellcome; 3.10.1996; appl. 28.3.1996; GB-prior. 30.3.1995).

|

|

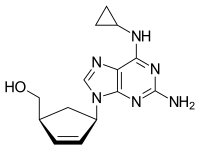

Chemical structure of abacavir

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˈbækəvɪər/ ( listen) listen) |

| Trade names | Ziagen, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699012 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

By mouth (solution or tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 83% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1.54 ± 0.63 h |

| Excretion | Kidney (1.2% abacavir, 30% 5′-carboxylic acid metabolite, 36% 5′-glucuronide metabolite, 15% unidentified minor metabolites). Fecal (16%) |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.149.341  |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H18N6O |

| Molar mass | 286.332 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 165 °C (329 °F) |

|

|

Chemical structure of abacavir

|

{(1S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]cyclopent-2-en-1-yl}methanol

(-)-cis-4-[2-Amino-6-(cyclopropylmethylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol

(1S, 4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H purin-9-yl]-2- cyclopentene-1 -methanol

Abacavir

Abacavir (ABC) is a powerful nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) used to treat HIV and AIDS. [Wikipedia] Chemically, it is a synthetic carbocyclic nucleoside and is the enantiomer with 1S, 4R absolute configuration on the cyclopentene ring. In vivo, abacavir sulfate dissociates to its free base, abacavir.

Abacavir (ABC)  i/ʌ.bæk.ʌ.vɪər/ is a nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) used to treat HIV and AIDS. It is available under the trade name Ziagen (ViiV Healthcare) and in the combination formulations Trizivir (abacavir, zidovudine andlamivudine) and Kivexa/Epzicom (abacavir and lamivudine). It has been well tolerated: the main side effect is hypersensitivity, which can be severe, and in rare cases, fatal. Genetic testing can indicate whether an individual will be hypersensitive; over 90% of patients can safely take abacavir. However, in a separate study, the risk of heart attack increased by nearly 90%.[1]

i/ʌ.bæk.ʌ.vɪər/ is a nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) used to treat HIV and AIDS. It is available under the trade name Ziagen (ViiV Healthcare) and in the combination formulations Trizivir (abacavir, zidovudine andlamivudine) and Kivexa/Epzicom (abacavir and lamivudine). It has been well tolerated: the main side effect is hypersensitivity, which can be severe, and in rare cases, fatal. Genetic testing can indicate whether an individual will be hypersensitive; over 90% of patients can safely take abacavir. However, in a separate study, the risk of heart attack increased by nearly 90%.[1]

Viral strains that are resistant to zidovudine (AZT) or lamivudine (3TC) are generally sensitive to abacavir (ABC), whereas some strains that are resistant to AZT and 3TC are not as sensitive to abacavir.

It is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[2]

Abacavir is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) with activity against Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1). Abacavir is phosphorylated to active metabolites that compete for incorporation into viral DNA. They inhibit the HIV reverse transcriptase enzyme competitively and act as a chain terminator of DNA synthesis. The concentration of drug necessary to effect viral replication by 50 percent (EC50) ranged from 3.7 to 5.8 μM (1 μM = 0.28 mcg/mL) and 0.07 to 1.0 μM against HIV-1IIIB and HIV-1BaL, respectively, and was 0.26 ± 0.18 μM against 8 clinical isolates. Abacavir had synergistic activity in cell culture in combination with the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) zidovudine, the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) nevirapine, and the protease inhibitor (PI) amprenavir; and additive activity in combination with the NRTIs didanosine, emtricitabine, lamivudine, stavudine, tenofovir, and zalcitabine.

Brief background information

| Salt | ATC | Formula | MM | CAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | J05AF06 | C 14 H 18 N 6 O | 286.34 g / mol | 136470-78-5 |

| succinate | J05AF06 | C 14 H 18 N 6 O · C 4 H 6 O | 356.43 g / mol | 168146-84-7 |

| sulfate | J05AF06 | C 14 H 18 N 6 O · 1 / 2H 2 SO 4 | 670.76 g / mol | 188062-50-2 |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

| {(1S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]cyclopent-2-en-1-yl}methanol | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Ziagen |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699012 |

| Pregnancy cat. | B3 (AU) C (US) |

| Legal status | POM (UK) ℞-only (US) |

| Routes | Oral (solution or tablets) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 83% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Half-life | 1.54 ± 0.63 h |

| Excretion | Renal (1.2% abacavir, 30% 5′-carboxylic acid metabolite, 36% 5′-glucuronide metabolite, 15% unidentified minor metabolites). Fecal (16%) |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 136470-78-5  |

| ATC code | J05AF06 |

| PubChem | CID 441300 |

| DrugBank | DB01048 |

| ChemSpider | 390063  |

| UNII | WR2TIP26VS  |

| KEGG | D07057  |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:421707  |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1380  |

| NIAID ChemDB | 028596 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C14H18N6O |

| Mol. mass | 286.332 g/mol |

Abacavir is a carbocyclic synthetic nucleoside analogue and an antiviral agent. Intracellularly, abacavir is converted by cellular enzymes to the active metabolite carbovir triphosphate, an analogue of deoxyguanosine-5′-triphosphate (dGTP). Carbovir triphosphate inhibits the activity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) both by competing with the natural substrate dGTP and by its incorporation into viral DNA. Viral DNA growth is terminated because the incorporated nucleotide lacks a 3′-OH group, which is needed to form the 5′ to 3′ phosphodiester linkage essential for DNA chain elongation.

Application

-

an antiviral agent, is used in the treatment of AIDS

-

ingibitor convertibility transkriptazы

Classes of substances

-

Adenine (6-aminopurines)

-

Aminoalcohols

-

Cyclopentenes and cyclopentadienes

-

Tsyklopropanы

-

-

-

| Country | Patent Number | Approved | Expires (estimated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 2289753 | 2007-01-23 | 2018-05-14 |

| Canada | 1340589 | 1999-06-08 | 2016-06-08 |

| Canada | 2216634 | 2004-07-20 | 2016-03-28 |

| United States | 6641843 | 2000-02-04 | 2020-02-04 |

| United States | 5089500 | 1992-12-26 | 2009-12-26 |

PATENT

US5034394

Synthesis pathway

Abacavir, (-) cis-[4-[2-amino-6-cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopenten-yl]-1 – methanol, a carbocyclic nucleoside which possesses a 2,3-dehydrocyclopentene ring, is referred to in United States Patent 5,034,394 as a reverse transcriptase inhibitor. Recently, a general synthetic strategy for the preparation of this type of compound and intermediates was reported [Crimmins, et. al., J. Org. Chem., 61 , 4192-4193 (1996) and 65, 8499-8509-4193 (2000)].

-

-

Abacavir is the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) of {(1S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-cyclopent-2-enyl}methanol and CAS No. 136470-78-5. Abacavir and therapeutically acceptable salts thereof, in particular the hemisulfate salt, are well-known as potent selective inhibitors of HIV-1 and HIV-2, and can be used in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

-

The structure of abacavir corresponds to formula (I):

-

EP 434450-A discloses certain 9-substituted-2-aminopurines including abacavir and its salts, methods for their preparation, and pharmaceutical compositions using these compounds.

-

Different preparation processes of abacavir are known in the art. In some of them abacavir is obtained starting from an appropriate pyrimidine compound, coupling it with a sugar analogue residue, followed by a cyclisation to form the imidazole ring and a final introduction of the cyclopropylamino group at the 6 position of the purine ring.

-

According to the teachings of EP 434450-A , the abacavir base is finally isolated by trituration using acetonitrile (ACN) or by chromatography, and subsequently it can be transformed to a salt of abacavir by reaction with the corresponding acid. Such isolation methods (trituration and chromatography) usually are limited to laboratory scale because they are not appropriate for industrial use. Furthermore, the isolation of the abacavir base by trituration using acetonitrile gives a gummy solid (Example 7) and the isolation by chromatography (eluted from methanol/ethyl acetate) yields a solid foam (Example 19 or 28).

-

Other documents also describe the isolation of abacavir by trituration or chromatography, but always a gummy solid or solid foam is obtained (cf. WO9921861 and EP741710 ), which would be difficult to operate on industrial scale.

-

WO9852949 describes the preparation of abacavir which is isolated from acetone. According to this document the manufacture of the abacavir free base produces an amorphous solid which traps solvents and is, therefore, unsuitable for large scale purification, or for formulation, without additional purification procedures (cf. page 1 of WO 9852949 ). In this document, it is proposed the use of a salt of abacavir, in particular the hemisulfate salt which shows improved physical properties regarding the abacavir base known in the art. Said properties allow the manufacture of the salt on industrial scale, and in particular its use for the preparation of pharmaceutical formulations.

-

However, the preparation of a salt of abacavir involves an extra processing step of preparing the salt, increasing the cost and the time to manufacture the compound. Generally, the abacavir free base is the precursor compound for the preparation of the salt. Thus, depending on the preparation process used for the preparation of the salt, the isolation step of the abacavir free base must also be done.

………………………………

http://www.google.co.in/patents/US5034394

EXAMPLE 21(-)-cis-4-[2-Amino-6-(cyclopropylmethylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol

The title compound of Example 7, (2.00 g, 6.50 mmol) was dissolved in 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2(1H)-pyrimidinone (Aldrich, 20 mL). Phosphoryl chloride (2.28 mL, 24.0 mmol) was added to the stirred, cooled (-10° C.) solution. After 3 minutes, cold water (80 mL) was added. The solution was extracted with chloroform (3×80 mL). The aqueous layer was diluted with ethanol (400 mL) and the pH adjusted to 6 with saturated aqueous NaOH. The precipitated inorganic salts were filtered off. The filtrate was further diluted with ethanol to a volume of 1 liter and the pH adjusted to 8 with additional NaOH. The resulting precipitate was filtered and dried to give the 5′-monophosphate of (±)-cis-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylmethylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol as white powder (4.0 mmoles, 62% quantitated by UV absorbance); HPLC analysis as in Example 17 shows one peak. This racemic 5′ -monophosphate was dissolved in water (200 mL) and snake venom 5′-nucleotidase (EC 3.1.3.5) from Crotalus atrox (5,000 IU, Sigma) was added. After incubation at 37° C. for 10 days, HPLC analysis as in Example 17 showed that 50% of the starting nucleotide had been dephosphorylated to the nucleoside. These were separated on a 5×14 cm column of DEAE Sephadex A25 (Pharmacia) which had been preequilibrated with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Title compound was eluted with 2 liters of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Evaporation of water gave white powder which was dissolved in methanol, adsorbed on silica gel, and applied to a silica gel column. Title compound was eluted with methanol:chloroform/1:9 as a colorless glass. An acetonitrile solution was evaporated to give white solid foam, dried at 0.3 mm Hg over P2 O5 ; 649 mg (72% from racemate); 1 H-NMR in DMSO-d6 and mass spectrum identical with those of the racemate (title compound of Example 7); [α]20 D -48.0°, [α]20 436 -97.1°, [α]20 365 -149° (c=0.14, methanol).

Anal. Calcd. for C15 H20 N6 O.0.10CH3 CN: C, 59.96; H, 6.72; N, 28.06. Found: C, 59.93; H, 6.76; N, 28.03.

Continued elution of the Sephadex column with 2 liters of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and then with 2 liters of 200 mM ammonium bicarbonate gave 5′-monophosphate (see Example 22) which was stable to 5′-nucleotidase.

…………………………………………

An enantiopure β-lactam with a suitably disposed electron withdrawing group on nitrogen, participated in a π-allylpalladium mediated reaction with 2,6-dichloropurine tetrabutylammonium salt to afford an advanced cis-1,4-substituted cyclopentenoid with both high regio- and stereoselectivity. This advanced intermediate was successfully manipulated to the total synthesis of (−)-Abacavir.

http://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2012/ob/c2ob06775g#!divAbstract

………………………………….

http://www.google.com.ar/patents/EP2085397A1?cl=en

Example 1: Preparation of crystalline Form I of abacavir base using methanol as solvent

-

[0026]Abacavir (1.00 g, containing about 17% of dichloromethane) was dissolved in refluxing methanol (2.2 mL). The solution was slowly cooled to – 5 °C and, the resulting suspension, was kept at that temperature overnight under gentle stirring. The mixture was filtered off and dried under vacuum (7-10 mbar) at 40 °C for 4 hours to give a white solid (0.55 g, 66% yield, < 5000 ppm of methanol). The PXRD analysis gave the diffractogram shown in FIG. 1.

……………………………………..

http://www.google.com/patents/WO2008037760A1?cl=en

Abacavir, is the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) of {(1 S,4R)-4-[2- amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-cyclopent-2-enyl}methanol, and CAS No. 136470-78-5. Abacavir sulfate is a potent selective inhibitor of HIV-1 and HIV-2, and can be used in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

The structure of abacavir hemisulfate salt corresponds to formula (I):

(I)

EP 434450-A discloses certain 9-substituted-2-aminopuhnes including abacavir and its salts, methods for their preparation, and pharmaceutical compositions using these compounds.

Different preparation processes of abacavir are known in the art. In some of them abacavir is obtained starting from an appropriate pyrimidine compound, coupling it with a sugar analogue residue, followed by a cyclisation to form the imidazole ring and a final introduction of the cyclopropylamino group at the 6 position of the purine ring. Pyrimidine compounds which have been identified as being useful as intermediates of said preparation processes include N-2-acylated abacavir intermediates such as N-{6- (cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]-9H-purin- 2-yl}acetamide or N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-

(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]-9H-purin-2-yl}isobutyramide. The removal of the amino protective group of these compounds using acidic conditions is known in the art. According to Example 28 of EP 434450-A, the amino protective group of the N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4- (hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]-9H-purin-2-yl}isobutyramide is removed by stirring with 1 N hydrochloric acid for 2 days at room temperature. The abacavir base, after adjusting the pH to 7.0 and evaporation of the solvent, is finally isolated by trituration and chromatography. Then, it is transformed by reaction with an acid to the corresponding salt of abacavir. The main disadvantages of this method are: (i) the use of a strongly corrosive mineral acid to remove the amino protective group; (ii) the need of a high dilution rate; (iii) a long reaction time to complete the reaction; (iv) the need of isolating the free abacavir; and (v) a complicated chromatographic purification process.

Thus, despite the teaching of this prior art document, the research of new deprotection processes of a N-acylated {(1 S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6- (cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-cyclopent-2-enyl}methanol is still an active field, since the industrial exploitation of the known process is difficult, as it has pointed out above. Thus, the provision of a new process for the removal of the amino protective group of a N-acylated {(1 S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6-

(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-cyclopent-2-enyl}methanol is desirable.

Example 1 : Preparation of abacavir hemisulfate

N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]-9H- purin-2-yl}isobutyramide (6.56 g, 18.40 mmol) was slurried in a mixture of isopropanol (32.8 ml) and 10% solution of NaOH (36.1 ml, 92.0 mmol). The mixture was refluxed for 1 h. The resulting solution was cooled to 20-25 0C and tert-butyl methyl ether (32.8 ml) was added. The layers were separated and H2SO4 96% (0.61 ml, 11.03 mmol) was added dropwise to the organic layer. This mixture was cooled to 0-50C and the resulting slurry filtered off.

The solid was dried under vacuum at 40 0C. Abacavir hemisulfate (5.98 g, 97%) was obtained as a white powder.

Example 6: Preparation of abacavir

N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]-9H- purin-2-yl}isobutyramide (1.0 g, 2.80 mmol) was slurried in a mixture of isopropanol (2 ml) and 10% solution of NaOH (1.1 ml, 2.80 mmol). The mixture was refluxed for 1 h. The resulting solution was cooled to 20-25 0C and tert-butyl methyl ether (2 ml) was added. The aqueous layer was discarded, the organic phase was cooled to 0-5 0C and the resulting slurry filtered off. The solid was dried under vacuum at 400C. Abacavir (0.62 g, 77%) was obtained as a white powder.

Example 7: Preparation of abacavir

N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]-9H- purin-2-yl}isobutyramide (1.25 g, 3.51 mmol) was slurried in a mixture of isopropanol (2.5 ml) and 10% solution of NaOH (1.37 ml, 3.51 mmol). The mixture was refluxed for 1 h and concentrated to dryness. The residue was crystallized in acetone. Abacavir (0.47 g, 47%) was obtained as a white powder.

Example 8: Preparation of abacavir

N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]-9H- purin-2-yl}isobutyramide (1.25 g, 3.51 mmol) was slurried in a mixture of isopropanol (2.5 ml) and 10% solution of NaOH (1.37 ml, 3.51 mmol). The mixture was refluxed for 1 h and concentrated to dryness. The residue was crystallized in acetonitrile. Abacavir (0.43 g, 43%) was obtained as a white powder.

Example 9: Preparation of abacavir

A mixture of N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent- 2-enyl]-9H-purin-2-yl}isobutyramide (10 g, 28 mmol), isopropanol (100 ml) and 10% solution of NaOH (16.8 ml, 42 mmol) was refluxed for 1 h. The resulting solution was cooled to 20-25 0C and washed several times with 25% solution of NaOH (10 ml). The wet organic layer was neutralized to pH 7.0-7.5 with 17% hydrochloric acid and it was concentrated to dryness under vacuum. The residue was crystallized in ethyl acetate (150 ml) to afford abacavir (7.2 g, 90%).

Example 10: Preparation of abacavir

A mixture of N-{6-(cyclopropylamino)-9-[(1 R,4S)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent- 2-enyl]-9H-purin-2-yl}isobutyramide (10 g, 28 mmol), isopropanol (100 ml) and 10% solution of NaOH (16.8 ml, 42 mmol) was refluxed for 1 h. The resulting solution was cooled to 20-25 0C and washed several times with 25% solution of NaOH (10 ml). The wet organic layer was neutralized to pH 7.0-7.5 with 17% hydrochloric acid and it was concentrated to dryness under vacuum. The residue was crystallized in acetone (300 ml) to afford abacavir (7.0 g, 88%).

…………………………………

http://www.google.com/patents/WO2004089952A1?cl=en

Abacavir of formula (1) :

or (1 S,4R)-4-[2-Amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1 – methanol and its salts are nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Abacavir sulfate is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor and used in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Abacavir sulfate and related compounds and their therapeutic uses are disclosed in US 5,034,394.

Crystalline forms of abacavir sulfate have not been reported in the literature. Moreover, the processes described in the literature do not produce abacavir sulfate in a stable, well-defined and reproducible crystalline form. It has now been discovered that abacavir sulfate can be prepared in three stable, well-defined and consistently reproducible crystalline forms.

Example 1

Abacavir free base (3.0 gm, obtained by the process described in example 21 of US 5,034,394) is dissolved in ethyl acetate (15 ml) and cone, sulfuric acid (0.3 ml) is added to the solution. Then the contents are stirred for 3 hours at 20°C and filtered to give 3.0 gm of form I abacavir sulfate. Example 2 Abacavir free base (3.0 gm) is dissolved in acetone (20 ml) and cone, sulfuric acid (0.3 ml) is added to the solution. Then the contents are stirred for 6 hours at 25°C and filtered to give 2.8 gm of form I abacavir sulfate.

Example 3 Abacavir free base (3.0 gm) is dissolved in acetonitrile (15 ml) and sulfuric acid (0.3 ml) is added to the solution. Then the contents are stirred for 2 hours at 25°C and the separated solid is filtered to give 3.0 gm of form II abacavir sulfate.

Example 4 Abacavir free base (3.0 gm) is dissolved in methyl tert-butyl ether (25 ml) and sulfuric acid (0.3 ml) is added to the solution. Then the contents are stirred for 1 hours at 25°C and the separated solid is filtered to give 3.0 gm of form II abacavir sulfate.

Example 5 Abacavir free base (3.0 gm) is dissolved in methanol (15 ml) and sulfuric acid (0.3 ml) is added to the solution. The contents then are cooled to 0°C and diisopropyl ether (15 ml) is added. The reaction mass is stirred for 2 hours at about 25°C and the separated solid is filtered to give 3.0 gm of form III abacavir sulfate

…………………………….

http://www.google.com.ar/patents/WO1999021861A1?cl=en

The present invention relates to a new process for the preparation of the chiral nucleoside analogue (1S, 4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H purin-9-yl]-2- cyclopentene-1 -methanol (compound of Formula (I)).

The compound of formula (I) is described as having potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) in EPO34450.

Results presented at the 34th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (October 4-7, 1994) demonstrate that the compound of formula I has significant activity against HIV comparable to, and if not better than, some current anti HIV drugs, such as zidovudine and didanosine.

Currently the compound of Formula (I) is undergoing clinical investigation to determine its safety and efficacy in humans. Therefore, there exists at the present time a need to supply large quantities of this compound for use in clinical trials.

Current routes of synthesising the compound of formula (I) involve multiple steps and are relatively expensive. It will be noted that the compound has two centres of asymmetry and it is essential that any route produces the compound of formula (I) substantially free of the corresponding enantiomer, preferably the compound of formula (I) is greater than 95% w/w free of the corresponding enantiomer.

Processes proposed for the preparation of the compound of formula (I) generally start from a pyrimidine compound, coupling with a 4-amino-2-cyclopentene-1- methanol analogue, cyciisation to form the imidazole ring and then introduction of the cyclopropylamine group into the 6 position of the purine, such routes include those suggested in EPO434450 and WO9521161. Essentially both routes disclosed in the two prior patent applications involve the following steps:-

(i) coupling (1S, 4R)-4-amino-2-cyclopentene-1 -methanol to N-(4,6-dichloro-5- formamido-2-pyrimidinyl) acetamide or a similar analogue thereof, for example N- (2-amino-4,6-dichloro-5-pyrimidinyl) formamide;

(ii) ring closure of the resultant compound to form the intermediate (1 S, 4R)-4- (2-amino-6-chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)-2-cyclopentene-1 -methanol;

(iii) substituting the halo group by a cyclopropylamino group on the 6 position of the purine ring.

The above routes are multi-step processes. By reducing the number of processing steps significant cost savings can be achieved due to the length of time to manufacture the compound being shortened and the waste streams minimised.

An alternative process suggested in the prior art involves the direct coupling of carbocyclic ribose analogues to the N atom on the 9 position of 2-amino-6-chloro purine. For example WO91/15490 discloses a single step process for the formation of the (1S, 4R)- 4-(2-amino-6-chloro-9H-purin-9-yl)-2-cyclopentene-1- methanol intermediate by reacting (1S, 4R)-4-hydroxy-2-cyclopentene-1 -methanol, in which the allylic hydroxyl group has been activated as an ester or carbonate and the other hydroxyl group has a blocking group attached (for example 1 ,4- bis- methylcarbonate) with 2-amino-6-chloropurine.

However we have found that when synthesising (1S, 4R)-4-(2-amino-6-chloro-9H- purin-9-yl)-2-cyclopentene-1- methanol by this route a significant amount of an N- 7 isomer is formed (i.e. coupling has occurred to the nitrogen at the 7- position of the purine ring) compared to the N-9 isomer desired. Further steps are therefore required to convert the N-7 product to the N-9 product, or alternatively removing the N-7 product, adding significantly to the cost. We have found that by using a transition metal catalysed process for the direct coupling of a compound of formula (II) or (III),

Example 1 (1 S. 4R)-4-[2-Amino-6-(cvclopropylamino)-9H purin-9-vπ-2-cvclopentene-1 – methanol

Triphenylphosphine (14mg) was added, under nitrogen, to a mixture of (1S.4R)- 4-hydroxy-2-cyclopentene -1 -methanol bis(methylcarbonate) (91 mg), 2-amino-6- (cyclopropylamino) purine (90mg), tris(dibenzylideneacetone)dipalladium (12mg) and dry DMF (2ml) and the resulting solution stirred at room temperature for 40 min.

The DMF was removed at 60° in vacuo and the residue partitioned between ethyl acetate (25ml.) and 20% sodium chloride solution (10ml.). The ethyl acetate solution was washed with 20% sodium chloride (2x12ml.) and with saturated sodium chloride solution, then dried (MgSO4) and the solvent removed in vacuo.

The residue was dissolved in methanol (10ml.), potassium carbonate (17mg) added and the mixture stirred under nitrogen for 15h.

The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue chromatographed on silica gel

(Merck 9385), eluting with dichloromethane-methanol [(95:5) increasing to (90:10)] to give the title compound (53mg) as a cream foam.

δ(DMSO-d6): 7.60 (s.1 H); 7.27 (s,1 H); 6.10 (dt,1 H); 5.86 (dt, 1 H); 5.81 (s,2H); 5.39 (m,1H); 4.75 (t,1H); 3.44 (t,2H); 3.03 (m, 1H): 2.86 (m,1H);2.60 (m,1H); 1.58 (dt, 1 H); 0.65 (m, 2H); 0.57 (m,2H).

TLC SiO2/CHCI3-MeOH (4:1 ) Rf 0.38; det. UN., KMnO4

Trade Names

| Page | Trade name | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | Kiveksa | GlaxoSmithKline |

| Trizivir | -»- | |

| Ziagen | -»- | |

| France | Kiveksa | -»- |

| Trizivir | -»- | |

| Ziagen | -»- | |

| United Kingdom | Kiveksa | -»- |

| Trizivir | -»- | |

| Ziagen | -»- | |

| Italy | Trizivir | -»- |

| Ziagen | -»- | |

| Japan | Épzikom | -»- |

| Ziagen | -»- | |

| USA | Épzikom | -»- |

| Trizivir | -»- | |

| Ziagen | -»- | |

| Ukraine | Virol | Ranbaksi Laboratories Limited, India |

| Ziagen | GlaksoSmitKlyayn Inc.., Canada | |

| Abamun | Tsipla Ltd, India | |

| Abacavir sulfate | Aurobindo Pharma Limited, India |

Formulations

-

Oral solution 20 mg / ml;

-

Tablets of 300 mg (as the sulfate);

-

Trizivir tablets 300 mg – abacavir in fixed combination with 150 mg of lamivudine and 300 mg zidovudine

ZIAGEN is the brand name for abacavir sulfate, a synthetic carbocyclic nucleoside analogue with inhibitory activity against HIV-1. The chemical name of abacavir sulfate is (1S,cis)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol sulfate (salt) (2:1). Abacavir sulfate is the enantiomer with 1S, 4R absolute configuration on the cyclopentene ring. It has a molecular formula of (C14H18N6O)2•H2SO4 and a molecular weight of 670.76 daltons. It has the following structural formula:

|

Abacavir sulfate is a white to off-white solid with a solubility of approximately 77 mg/mL in distilled water at 25°C. It has an octanol/water (pH 7.1 to 7.3) partition coefficient (log P) of approximately 1.20 at 25°C.

ZIAGEN Tablets are for oral administration. Each tablet contains abacavir sulfate equivalent to 300 mg of abacavir as active ingredient and the following inactive ingredients: colloidal silicon dioxide, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, and sodium starch glycolate. The tablets are coated with a film that is made of hypromellose, polysorbate 80, synthetic yellow iron oxide, titanium dioxide, and triacetin.

ZIAGEN Oral Solution is for oral administration. Each milliliter (1 mL) of ZIAGEN Oral Solution contains abacavir sulfate equivalent to 20 mg of abacavir (i.e., 20 mg/mL) as active ingredient and the following inactive ingredients: artificial strawberry and banana flavors, citric acid (anhydrous), methylparaben and propylparaben (added as preservatives), propylene glycol, saccharin sodium, sodium citrate (dihydrate), sorbitol solution, and water.

In vivo, abacavir sulfate dissociates to its free base, abacavir. All dosages for ZIAGEN are expressed in terms of abacavir.

History

Abacavir was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 18, 1998 and is thus the fifteenth approved antiretroviral drug in the United States. Its patent expired in the United States on 2009-12-26.

Links

-

US 5 089 500 (Burroughs Wellcome; 18.2.1992; GB-prior. 27.6.1988).

-

Synthesis a)

-

EP 434 450 (Wellcome Found .; 26.6.1991; appl. 21.12.1990; prior-USA. 22.12.1989).

-

Crimmins, MT et al .: J. Org. Chem. (JOCEAH) 61 4192 (1996).

-

EP 1 857 458 (Solmag; appl. 5.5.2006).

-

EP 424 064 (Enzymatix; appl. 24.4.1991; GB -prior. 16.10.1989).

-

U.S. 6 340 587 (Beecham SMITHKLINE; 22.1.2002; appl. 20.8.1998; GB -prior. 22.8.1997).

-

-

Синтез b)

-

Olivo, HF et al .: J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 (JCPRB4) 1998, 391.

-

-

Preparation c)

-

U.S. 5 034 394 (Wellcome Found .; 23.7.1991; appl. 22.12.1989; GB -prior. 27.6.1988).

-

-

Synthesis d)

-

WO 9 924 431 (Glaxo; appl. 12.11.1998; WO-prior. 12.11.1997).

-

| WO2008037760A1 * | Sep 27, 2007 | Apr 3, 2008 | Esteve Quimica Sa | Process for the preparation of abacavir |

| EP1905772A1 * | Sep 28, 2006 | Apr 2, 2008 | Esteve Quimica, S.A. | Process for the preparation of abacavir |

| US8183370 | Sep 27, 2007 | May 22, 2012 | Esteve Quimica, Sa | Process for the preparation of abacavir |

| EP0434450A2 | 21 Dec 1990 | 26 Jun 1991 | The Wellcome Foundation Limited | Therapeutic nucleosides |

| EP0741710A1 | 3 Feb 1995 | 13 Nov 1996 | The Wellcome Foundation Limited | Chloropyrimide intermediates |

| WO1998052949A1 | 14 May 1998 | 26 Nov 1998 | Glaxo Group Ltd | Carbocyclic nucleoside hemisulfate and its use in treating viral infections |

| WO1999021861A1 | 24 Oct 1997 | 6 May 1999 | Glaxo Group Ltd | Process for preparing a chiral nucleoside analogue |

| WO1999039691A2 * | 4 Feb 1999 | 12 Aug 1999 | Brooks Nikki Thoennes | Pharmaceutical compositions |

| WO2008037760A1 * | 27 Sep 2007 | 3 Apr 2008 | Esteve Quimica Sa | Process for the preparation of abacavir |

References

- Jump up^ SFGate.com

- Jump up^ “WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines”. World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Jump up^ https://online.epocrates.com/noFrame/showPage.do?method=drugs&MonographId=2043&ActiveSectionId=5

- Jump up^ Mallal, S., Phillips, E., Carosi, G. et al. (2008). “HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir”. New England Journal of Medicine 358: 568–579.doi:10.1056/nejmoa0706135.

- Jump up^ Rauch, A., Nolan, D., Martin, A. et al. (2006). “Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study”. Clinical Infectious Diseases 43: 99–102. doi:10.1086/504874.

- Jump up^ Heatherington et al. (2002). “Genetic variations in HLA-B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir”. Lancet 359: 1121–1122.

- Jump up^ Mallal et al. (2002). “Association between presence of HLA*B5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir”. Lancet359: 727–732. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x.

- Jump up^ Rotimi, C.N.; Jorde, L.B. (2010). “Ancestry and disease in the age of genomic medicine”. New England Journal of Medicine 363: 1551–1558.

- Jump up^ Phillips, E., Mallal, S. (2009). “Successful translation of pharmacogenetics into the clinic”. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy 13: 1–9. doi:10.1007/bf03256308.

- Jump up^ Phillips, E., Mallal S. (2007). “Drug hypersensitivity in HIV”. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology 7: 324–330. doi:10.1097/aci.0b013e32825ea68a.

- Jump up^http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm123927.htmAccessed November 29, 2013.

- Jump up^ http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=ca73b519-015a-436d-aa3c-af53492825a1

- Jump up^ Martin MA, Hoffman JM, Freimuth RR et al. (May 2014). “Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for HLA-B Genotype and Abacavir Dosing: 2014 update”. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 95 (5): 499–500. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.38.PMC 3994233. PMID 24561393.

- Jump up^ Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, de Boer A et al. (May 2011). “Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte–an update of guidelines”. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 89 (5): 662–73.doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.34. PMID 21412232.

- Jump up^ Shear, N.H., Milpied, B., Bruynzeel, D.P. et al. (2008). “A review of drug patch testing and implications for HIV clinicians”. AIDS 22: 999–1007.doi:10.1097/qad.0b013e3282f7cb60.

- Jump up^ http://www.drugs.com/fda/abacavir-ongoing-safety-review-possible-increased-risk-heart-attack-12914.html Accessed November 29, 2013.

- Jump up^ Ding X, Andraca-Carrera E, Cooper C et al. (December 2012). “No association of abacavir use with myocardial infarction: findings of an FDA meta-analysis”. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 61 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826f993c.PMID 22932321.

- Illing PT et al. 2012, Nature, doi:10.1038/nature11147

External links

- Full Prescribing Information

- Abacavir pathway on PharmGKB

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG)

EXTRA INFO

How to obtain carbocyclic nucleosides?

Carbocyclic nucleosides are synthetically the most challenging class of nucleosides, requiring multi-step and often elaborate synthetic pathways to introduce the necessary stereochemistry. There are two main strategies for the preparation of carbocyclic nucleosides. In the linear approach a cyclopentylamine is used as starting material and the heterocycle is built in a stepwise manner (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Linear approach for the synthesis of abacavir.[5]

The more flexible strategy is a convergent approach: a functionalized carbocyclic moiety is condensed with a heterocycle rapidly leading to a variety of carbocyclic nucleosides. Initially, we started our syntheses from cyclopentadiene 1 that is deprotonated and alkylated with benzyloxymethyl chloride to give the diene 2. This material is converted by a hydroboration into cyclopentenol 3 or isomerized into two thermodynamically more stable cyclopentadienes 4a,b. With the protection and another hydroboration step to 5 we gain access to an enantiomerically pure precursor for the synthesis of a variety of carbocyclic 2’-deoxynucleosides e.g.:carba-dT, carba-dA or carba-BVDU.[6] The isomeric dienes 4a,b were hydroborated to the racemic carbocyclic moiety 6.

Scheme 2: Convergent approach for the synthesis of carba-dT.

The asymmetric synthesis route and the racemic route above are short and efficient ways to diverse carbocyclic D- or L-nucleosides (Scheme 2). Different heterocycles can be condensed to these precursors leading to carbocyclic purine- and pyrimidine-nucleosides. Beside α- and β-nucleosides, carbocyclic epi– andiso-nucleosides in the 2’-deoxyxylose form were accessable.[7]

What else is possible? The racemic cyclopentenol 6 can be coupled by a modified Mitsunobu-reaction.Moreover, this strategy offers the possibility of synthesizing new carbocyclic nucleosides by functionalizing the double bond before or after introduction of the nucleobase (scheme 3).[8]

Scheme 3: Functionalized carbocyclic nucleosides based on cyclopentenol 6.

Other interesting carbocyclic precursors like cyclopentenol 7 can be used to synthesize several classes of carbocyclic nucleoside analogues, e.g.: 2’,3’-dideoxy-2’,3’-didehydro nucleosides (d4-nucleosides), 2’,3’-dideoxynucleosides (ddNs), ribonucleosides, bicyclic nucleosides or even 2’-fluoro-nucleosides.

Scheme 4: Functionalized carbocyclic thymidine analogues based on cyclopentenol 7.

[1] V. E. Marquez, T. Ben-Kasus, J. J. Barchi, K. M. Green, M .C. Nicklaus, R. Agbaria, J. Am. Chem. Soc.2004,126, 543.

[2] A. D. Borthwick, K. Biggadike, Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 571.

[3] H. Bricaud, P. Herdewijn, E. De Clercq, Biochem. Pharmacol. 1983, 3583.

[4] P. L. Boyer, B. C. Vu, Z. Ambrose, J. G. Julias, S. Warnecke, C. Liao, C. Meier, V. E. Marquez, S. H. Hughes, J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 5356.

[5] S. M. Daluge, M. T. Martin, B. R. Sickles, D. A. Livingston, Nucleosides, Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2000,19, 297.

[6] O. R. Ludek, C. Meier, Synthesis 2003, 2101.

[7] O. R. Ludek, T. Kraemer, J. Balzarini, C. Meier, Synthesis 2006, 1313.

[8] M. Mahler, B. Reichardt, P. Hartjen, J. van Lunzen, C. Meier, Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 11046-11062.

![Robert Priest - People Like You and Me (2024) [Hi-Res]](http://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-07/1751805912_lhttl01vuwv8a_600.jpg)